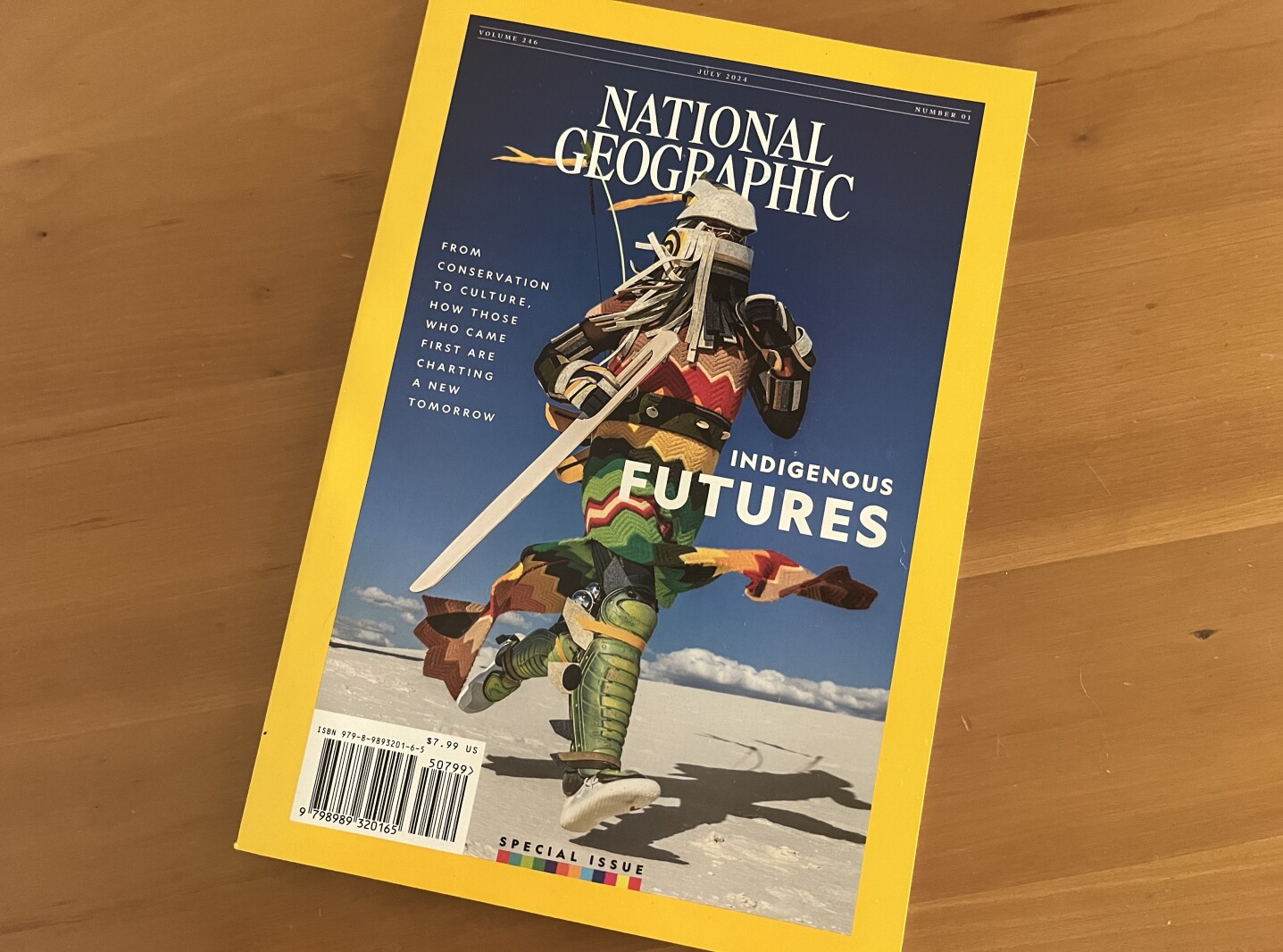

FARGO — Two artists with ties to Fargo and the Plains Art Museum are featured prominently in a new

special issue National Geographic

that looks at the future of Indigenous art and culture.

The work of Cannupa Hanska Luger, who was born in Fort Yates, N.D., on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, is featured on the cover. A painting by Fargo resident Star WallowingBull is featured inside.

Contributed / Rik Sferra

“It’s quite a surprise. I’m thrilled about it,” WallowingBull said.

The 2021 painting, “Teewinot” shows WallowingBull’s signature use of bright, bold color and crisp lines, depicting an indigenous dancer by a flower. The title is a Shoshone word for “many peaks.”

“Drawing inspiration for this painting from the dynamic movements and gestures of powwow dancers in colorful regalia — as well as the Teton mountains’ Teewinot peak and even Scandinavian floral elements — WallowingBull blends cultural symbolism and futurism,” a description in National Geographic stated. “In this way, the Fargo, North Dakota, resident reminds viewers that, ‘the traditional and the technological belong together.'”

Alyssa Goelzer / The Forum

WallowingBull, who is of Ojibwa and Arapaho descent, has had three solo shows at the Plains in the last 25 years, including his latest, “Transformer” in 2015.

Contributed

“These are great examples of how we perceive Native people in a futuristic context,” said Delia Touche, the new director of the Indigenous programming at the Plains Art Museum.

“We’re contemporary people, we like technology as well as anyone. We can adapt to whatever obstacles that are thrown at us,” Touche said.

A member of the Spirit Lake Nation in north central North Dakota, Touche is a 2020 Minnesota State University of Moorhead Graduate and printmaker, bookmaker and fiber artist.

WallowingBull said the magazine was looking for futuristic artists.

“I fit that description,” he said.

Contributed / Star WallowingBull

He likes the description, but he avoids labels, like “Indigenous artist.”

“I can understand if people want to say that. Back then (a decade ago) it would bother me, but it doesn’t bother me anymore,” he said in 2015. “Doors open regardless of if they want me to be a Native American artist. There are Native American artists who look at (my work) and say, ‘This isn’t Indian art.’ I say, ‘I never said I was an Indian artist. It’s just my art.’ I’m just an artist that likes to make art.”

“Teewinot” was influenced not only by his Indigenous heritage as well as the Scandinavian heritage now common in the Dakotas and Minnesota, but also by the Transformers toys, TV shows and movies.

“I love Transformers,” WallowingBull said.

WallowingBull started drawing while living with his dad, Minneapolis-based artist Frank Big Bear. He grew up drawing, inspired by his father’s own vivid, multi-dimensional Prismacolor drawings. WallowingBull developed his own style and impressed famed pop artist James Rosenquist so much that the elder painter bought one of his first paintings and encouraged him to focus on painting instead of drawing. WallowingBull would continue to both.

Contributed

“I’ve got my father’s influence and Rosenquist’s influence and they’re blended in my imagery,” WallowingBull said in 2015.

WallowingBull recently won a

$10,000 Jim Denomie Memorial Scholarship

, awarded annually, “to a Native artist who best exemplifies the values Jim demonstrated in his own career: commitment to excellence; generosity of spirit; and engagement in community,” the scholarship’s website states. WallowingBull was friends with the Ojibwe painter who died in 2022.

Stills from Hanska Luger’s 2021 video “Future Ancestral Technologies: New Myth” are featured on the cover and inside the issue of National Geographic.

Contributed /Plains Art Museum

Hanska Luger, who is based in Glorieta, New Mexico, is described in the magazine as placing “an optimistic emphasis on Native peoples’ proven ability to adapt to a changing world.”

“He delves into speculative fiction to present a future, ‘where we’re in right relationship with our environment and our kin,'” as described in the article. The work depicted is part of a series using installation, video, and performance art that tells “an ongoing narrative about combating societal ills. Among these, according to Luger, are capitalism and colonialism, which manifest as corporeal monsters. Set in an undetermined time, the video shows heroic ‘monster slayers’ bringing water to a barren landscape. The desert reciprocates, providing tools for confronting the evil forces.”

Hanska Luger was raised by his mother, who is Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Lakota, in the Southwest but would return to North Dakota in the summer to work on the ranch of his father, who is of Austrian and Norwegian descent.

Contributed / Plains Art Museum

Luger graduated with honors in 2011 from the Institute of American Indian Arts with a focus on ceramics. His 2015 two-week residency at the Plains focused on making ocarinas, globular clay flutes made by different cultures around the world.

“At some point, everyone’s ancestors made some kind of clay flute. So to me, it’s making something we all share in,” he said at the time.

Hanska Luger also said he avoids referring to himself as an Indigenous artist.

“I am both of those things. I don’t say I’m an Indian artist, but my heritage, my symbolism is Native at its core,” he said in 2015. “It’s such a rich, visual heritage. I have this ability to draw from it without any appropriation. It’s beautiful. I like to do my work and blur the lines. I’ve yet to meet a person on this planet who is not indigenous to here. If you meet one, point it out.”

Kari Rowe, who is Ogalala Lakota, Turtle Mountain Ojibwe, from South and North Dakota, contributed photos for a story on Indigenous chef Sherry Pocknett in the magazine. View the publication online at