When Glicéria Tupinambá, an Indigenous Brazilian artist, first visited the Quai Branly Museum in Paris, she had an encounter that would change her life.

It was 2018 and museum officials had invited Glicéria — a member of the Tupinambá people — to see a mantle, or feathered cape, that her ancestors had made hundreds of years ago. Glicéria expected to simply study the artifact, she recalled in a recent interview. But upon seeing its plumage, she said, she started experiencing spectacular visions.

“Suddenly, I see myself facing an ancestor,” Glicéria recalled, “and this ancestor shows me images from the past, and speaks to me with this vast and female energy.”

Glicéria set out to learn everything she could about the capes, including how to make them herself. She also started a “treasure hunt,” to find other mantels that Europeans had obtained from her homeland, so that she could commune with them and, potentially, take some back to the Tupinambá in Bahia, Brazil.

For much of the past decade, restitution — the idea that Western museums should return contested artifacts to their countries of origin — has been a major topic of debate among museum administrators, lawmakers and activists. And while artists’ voices have not been as loud in those discussions, Glicéria is among several at this year’s Venice Biennale, the international art exhibition that runs through Nov. 24, showing work that draws focus to the issue.

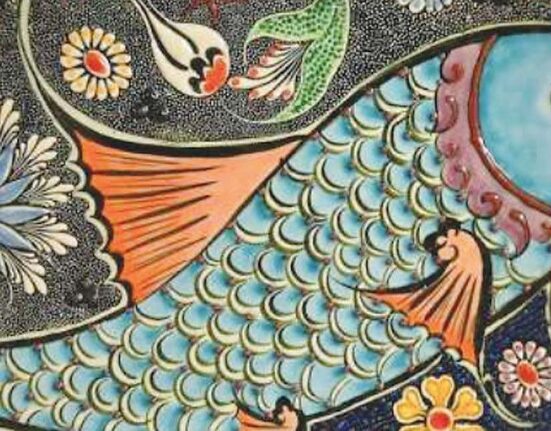

In the Brazilian pavilion, Glicéria, 41, is exhibiting an intricate, multicolored mantle that she made with the help of other Tupinambá. Alongside the cape, which they constructed using 4,200 feathers, wall text explains that seven European museums still hold mantles in their collections. (Last year, Denmark’s National Museum announced that it would return one cape to Brazil, but it still holds others.)

In Nigeria’s pavilion, Yinka Shonibare has made intricate clay replicas of about 150 Benin Bronzes — priceless artifacts that, in 1897, British soldiers looted from what is now Nigeria, and are now found in numerous European and American collections. And at Benin’s pavilion, an installation by Chloé Quenum, a French-Beninese artist, includes glass sculptures of musical instruments that were taken from the Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now Benin and are now in the Quai Branly’s storerooms.

Azu Nwagbogu, the curator of the Benin pavilion, said that it was unsurprising that artists were making work about the hot topic of restitution. But he said that the Biennale artists were also trying to provoke wider questions, including about artifacts’ past and present meanings, and about the unequal power dynamic between Western countries and the Global South, including in the art world.

One artist group at the Biennale is even using a temporarily returned cherished artifact in its exhibition. The Dutch pavilion, partly curated by the Amsterdam-based artist Renzo Martens, features sculptures and films by an artists’ collective in the Democratic Republic of Congo whom Martens often works with. For the Biennale, the collective secured the loan of a wooden artifact from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

The simple carved sculpture depicts Maximilien Balot, a Belgian colonial official who once forcibly recruited Congolese villagers to work on plantations. In 1931, during an uprising against colonial rule, some of the villagers killed Balot, then made a sculpture of him that they believed would trap his angry spirit. Decades later, a Western collector bought the sculpture and later sold it to the Virginia museum.

During the Biennale, the sculpture is on display at White Cube, an art space in Congo, and visitors to the Dutch pavilion in Venice can watch a livestream of the artifact in a case some 5,000 miles away. That distance and detachment, Martens said in an interview, puts Biennale visitors in the position that the Congolese were in before the object’s return.

“For the last 50 years, it’s only been available to Western audiences,” he said. “Now, it’s only available to people in the D.R.C.”

Matthieu Kasiama and Ced’Art Tamasala, two members of the Congolese collective, all of whom are former plantation workers themselves, said in an email exchange that the Balot’s temporary return had allowed their community “to reconnect with our ancestors” and their “spirit of resistance.” Now, the artists said, they wanted to use that spirit to “free ourselves from capitalist oppression.”

Kasiama and Tamasala said they were not pressing for the sculpture to be permanently displayed at the former Unilever-owned plantation where the collective is based. Instead, after the Biennale ends, they want it to travel to other plantations around the world to inspire resistance against international corporations. That is unlikely to happen anytime soon. A spokeswoman for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts said in an email that the Balot was merely on loan and would return to Richmond.

In Glicéria’s case, the restitution of any of her people’s capes would “spark a lot of joy” in Brazil, she said. It would also, she added, “give hope for other peoples who are fighting the same fight — the battle to have their ancestors back.”