Showing a bunch of form-fluid creatures occupying a confused habitat in which earth, water and sky appear to bleed into each other, Banduri’s digitally-drawn plea to view the connections between binary labels and ecological ruin will sit among other contemporary Indian works questioning the stereotypical depictions of gender in South Asian art at AOI, an exhibition organised by the Times of India. Featuring serpent goddesses and other marginalised bodies, this dedicated section wants to make visitors rethink cobwebbed scenes of history and mythology through a queer feminist post-colonial lens “that is centered around the Global South”.

“One of the most significant developments in visual art practices in India over the past few decades has been the beginning of a more considered understanding of gender and sexual identity by practitioners who claim their agency and create works that resonate globally but are still culturally specific…” writes curator Myna Mukherjee in her concept note on the segment which not only comprises traditional paintings, lithographs and sculptures but also digital new-age media, videos, sci-fi fantasia and comic-book graphic art.

Defying norms: Artists Sukanya Ayde’s diptych’ is influenced by miniatures

By making room for underrepresented groups such as women and queer artists in modern ways, these diverse works address “both contemporary and historical concerns within the Indian context” and challenge “the politics of invisibilization,” writes Mukherjee, who runs Engendered Delhi, a gallery that highlights contemporary artworks themed around gender. To hold a mirror to contemporary realities, “the generation of new knowledge is and must be part of our relationship to heritage art forms,” believes Mukherjee.

Which is why at AOI, visitors will find three Indian-miniature-style paintings called ‘Phases’, ‘Presence’ and ‘I Exist’. The titles lay bare the lush inner world of their young creator Sukanya Ayde. “Through my art I try to breathe, question and reclaim my legitimate space in this society,” says Ayde, an illustrator and textile designer who grew up converting into doodles the rich patterns and prints she noticed during her numerous trips to Rajasthan with her parents.

After graduating in history, Ayde chose to pursue art and found herself drawn to the populous landscapes of 19th-century neo-impressionist paintings. As much a fan of English painter and 1960s pop art legend David Hockney as of Pahari painting veterans Nainsukh and Manaku of Guler, Ayde–who plays the flute and has a penchant for interior decoration–draws her influences from both nature and Indian miniature. Many of her art pieces, she says, consciously depict feminine forms “to create spaces for them that are otherwise limited everywhere”. So, if ‘Presence’ “urges us to focus on the fluid and structural parts of our lives that coexist within us”, ‘I Exist’ “validates a sense of worthiness that is often questioned within a woman and gives voice to the practice of just being/existing”.

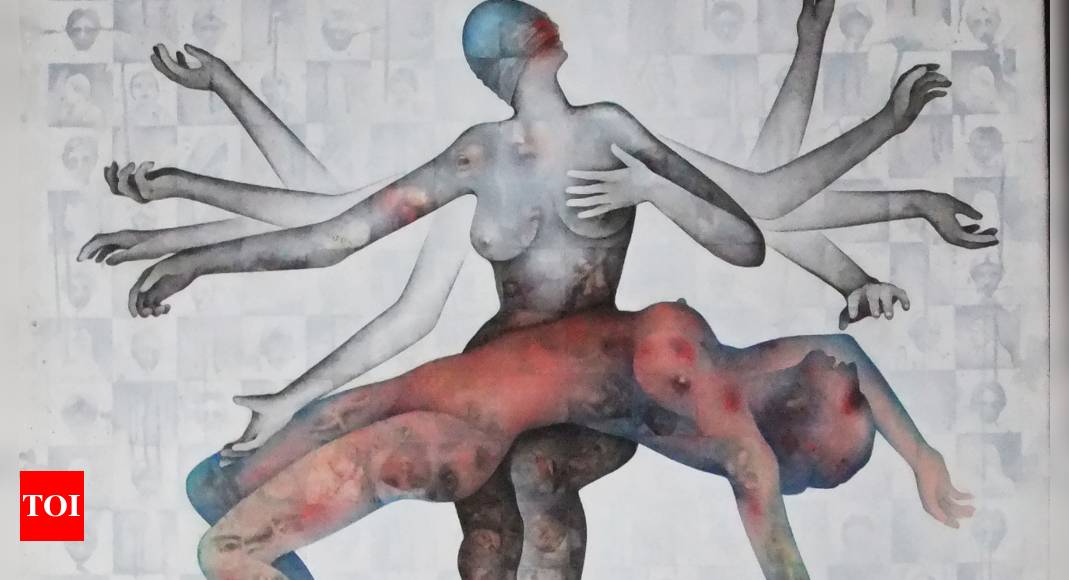

Dr Mandakini Devi’s canvases, on the other hand, give voice to the once-marginalised “hybrid bodies” such as Iran’s as ‘Shahmeran’ and India’s ‘Nag Kanyas’, which have been reclaimed as powerful fertility symbols in most archives of eastern cultures. Ranbir Kaleka, Puneet Kaushik, Rajat Sharma, Moutushi Chakraborty, Varnita Mahajan, Adil Kalim and Diana Mohapatra are among the other artists lending texture to the layered landscape of gender, home and identity at AOI.

However, it’s not just the subjects that defy the norm in form. Highlighted works of queer art by names such as Banduri, Raghava K K and Balbir Krishan–much like their creators–go beyond the binary in both message and medium. KK’s works such as ‘Into the Metaverse’, for instance, were created from a vast, high-tech palette consisting of AI, neuro-feedback, biohacking, video games, cryptocurrencies apart from painting, sculpture and performance. Experimenting with various media allows for new forms of expression, feels Banduri.

“Multi-disciplinary art is a new way to cast forward your heart, to not follow any rule,” says Banduri. If Banduri translates the vibrant mix of “illusion, imagery, emotion and desires” he saw in his vivid dreams as a child into sound animation, verse composition, electronic replicas, light installations and robotic and virtual media art, New York City-based Krishan reacts to domestic and sexual violence against women through multi-media artworks that bust tropes of misogyny and patriarchy in Indian mythology.

Born and raised in a farming village in India, Krishan described himself as a “a queer Indian-American man, a child sexual abuse survivor and permanently disabled from an early suicide attempt” in a recent article by the news portal Epicenter NYC. “I had a harsh childhood and a youth filled with loss and grief. Art guided me through darkness, gave me hope, led me toward light and made me more human,” said Krishan in the article. While Krishan’s paintings–which comment on the exalted fantasies of masculinity–have been celebrated by the arts fraternity, they have been censured by extremists in India.

At a miniature level, neo-miniaturist Ayde–who posts videos of herself painting–knows the feeling. Most viewers of her videos say they find her process “soothing” and even transcendental. However, when she posted a painting of a woman who is clad in a sari that does not cover her bare breasts–a recreation of an earlier miniature painting from Jaipur school of miniatures– Ayde faced flak from right wing fundamentalists on social media. This is perhaps why a platform such as AOI feels both urgent and important to Ayde. “Gender and sexuality are intrinsically relevant concepts in art and the world in general,” she says. “To represent current thought on these subjects, it is vital to put out works of emerging artists like myself and give them a voice.”