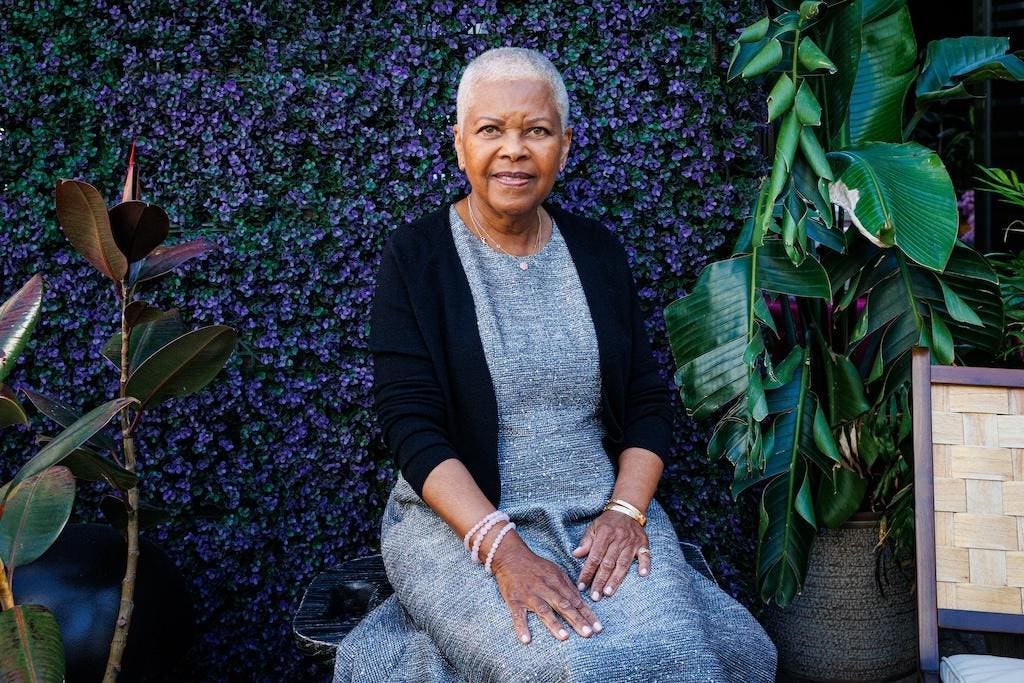

Eileen Harris Norton at ‘All These Liberations’ book launch and cocktail reception at Good Behavior … [+]

Viewing art engages our minds, emotions, senses, and imagination, boosting our mental health, expanding our world view, and helping to foster empathy necessary to understand and appreciate others and how we relate to our environments. Collecting art underscores that emotional connection, especially when we engage with the artists and their work, observing their creative process and space, and understanding and contextualizing their journey and creations.

Collecting art as a philanthropic pursuit, as an investment, or just because we like what we see, has value, as expanding the marketplace helps to support living artists or to preserve legacies. Regardless of how a collection begins or evolves, its deeper value is intrinsically aligned with the collector’s mission and conviction. While how the biggest collectors move markets may help to advance careers of living artists, provided they are fairly compensated, few transform art history by amplifying the artists through a consummate and comprehensive approach, guided by their own keen eye and gazing beyond what makes markets in any moment. Renowned art collector, social activist, arts patron, and Art+Practice co-founder Eileen Harris Norton exemplifies the latter.

“From the start, Eileen has intellectually pursued collecting, having the intention and an interest at the boundaries of ‘exclusion’ within art history and within the gallery world. She decided to develop close relationships with many curators and artists here in the United States and abroad. I remember conversations in the 1990s with Eileen about which artists she might find compelling, not for the sake of who or what was ‘new,’ but from the perspective of her experience and insights,” acclaimed photographer and multimedia artist Lorna Simpson, whose oeuvre explores themes and ideas relating to identity politics, writes in the foreword to the book and catalog All These Liberations: Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection. “As I understand it, her interests in collecting and philanthropy began with artists and curators. During the 1990s, who better to have many discussions with than Thelma Golden, then curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City?”

Telma Golden (left) and Lorna Simpson (right) at ‘All These Liberations’ book launch

Celebrating the work of women artists of color, All These Liberations features work by a wide range of pioneering artists, including Sonia Boyce, Maya Lin, Julie Mehretu, Shirin Neshat, Adrian Piper, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Sadie Barnette, Mona Hatoum, Ana Mendieta, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, Amy Sherald, Simpson, Mickalene Thomas, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Published in March by Yale University Press, and distributed by Marquand Books, the 272-page hardcover is available for $50.

Harris Norton began collecting art in 1976, buying The Exhorters (1976), a print by Los Angeles-based artist, printmaker, cultural organizer, activist, and arts advocate Ruth Waddy (1909-2003). Her mother, Rosalind Van Meter Harris, saw an ad in the Los Angeles Times announcing a printmaking workshop by Waddy at the Museum of African American Art (MAAA), founded by Waddy and printmaker, painter, and historian Samella Lewis (1923-2022). The two women met Waddy at the workshop, which inspired the purchase. The linoleum cut on wove paper depicts men, some with raised arms, who appear to be preaching as the title suggests, as a woman with a head covering observes.

“Of course, I had seen art—like Picassos and Monets and all the French Impressionists—but to see a Black woman artist in LA sitting there. . . .We were standing back, but my mom goes, ‘We’ve got to go talk to the lady,’ so we went up and said hello. My mom said, ‘You’ve got to buy something.’ My mom worked at Thrifty and was a working person, and then here was this woman who was older than my mom sitting there making art. We were wowed,” Harris Norton recalls in an interview with Golden, who is now director and chief curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City.

Harris Norton continues to advance the mission of Waddy and Lewis, who had hoped to stage an exhibition by local African-Americans artists, which Lewis described as a “civil and social” gathering. The exhibition never took place, but they formed a group called the Art West Associated, seeking funding and planning for exhibitions and collaborating with Black magazines, such as Essence, to help artists sell their prints.

Moreover, Harris Norton continues to lead and inspire a culture of thoughtful, relevant, and future-proof art collecting. “Eileen’s collecting methods and patron practices reflect her own sensible, aesthetic eye and are congruent with the many sociopolitical currents that have evolved throughout the world in recent decades, often mirroring avant-garde impulse,” editor Taylor Renee Aldridge writes in the introduction.

From left to right: Susan Cahan, Lorna Simpson, Thelma Golden, Eileen Harris Norton, Amy Sherald, … [+]

“Eileen, thank you for trusting me with this endeavor. It’s been a true pleasure to get to know you more of your collection and get to work with you on this endeavor. I really just appreciate your spirit, your generosity, and all that you’ve done for so many careers that have also been very impactful to my own career. So thank you,” Aldridge said at a May 31 cocktail reception at Good Behavior at the MADE Hotel in Manhattan, attended by esteemed guests, including Mark Bradford, Pamela Joyner, Sherald, Susan Cahan, Jordan Weber, and Fatimah Tuggar.

The evening before the elegant cocktail party, Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice, hosted a conversation between Golden and Harris Norton.

“I wouldn’t be here without Eileen,” Golden said at the Ideas at Ford conversation. “We can’t look at this moment, where we all revel in the fact we can go to museums all over the world and see the works of Black artists, women artists, queer artists, who used to be known as regional, without thinking about the ways that Eileen has collected—and to see that as a norm now. We have to understand how that happened.”

Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice, hosts a conversation … [+]