Like the colored sand mandalas painstakingly crafted by Tibetan Buddhist monks who ritually dismantle them once completed, Justin Bateman’s art is ephemeral. Using found pebbles as his medium, his stone mosaics only exist the time of their creation before he destroys them by scattering the stones back at their original location or letting the weather break them down. I speak to the artist about his creative process.

Describe to me your artistic language and philosophy.

The work also raises many more questions, especially with regard to its theme. The subjects can appear indiscriminate, largely evolving during meditations at the outset. Once the concept had manifested, I would consider the practical aspects of their composition, palette and capacity to be rendered in the range of stones available. I have created iconic artworks, spiritual figures, philosophers, political leaders, refugees and people I met on my travels. Whilst living in a forest cabin in Chiang Mai in northern Thailand, I met a man whose physiognomy I couldn’t resist: the local cattle herder. There was something idiosyncratic about creating this man’s portrait; constructing the man, upon the man’s land, from the land he worked. It was a reincarnation of his form, evolving and devolving like the entropy of life.

How do you come up with the subject matter for your artworks – is there a common theme linking them all?

Many of my later works were from suggestions or requests from followers, which I often sit with for weeks or months before creating. If a suitable location and stones present themselves at a similar time to the request, I will make the work. I look for signs from the universe to suggest this thing wants to exist. I consider myself an Omnist, I believe all spiritual practices have something to teach us. Spiritual practice is very important to me, whether it takes place in churches, temples and mosques or in forests, by mountains and beaches. The doctrine or belief system does not deter me from attempting to deepen my relationship with our creator. I try to hand my own will over regularly to be less selfish. In some ways, I think it’s sad that we took God out of the fish, the stones, the river, the air and put him or her out of reach, dressed in elaborate uniforms in conceptual stories and books. I’m not sure I need a rigid narrative to cultivate my faith. If we are patient and persevere, we can observe the essence of creation in all things. Its emergence is available in awareness itself.

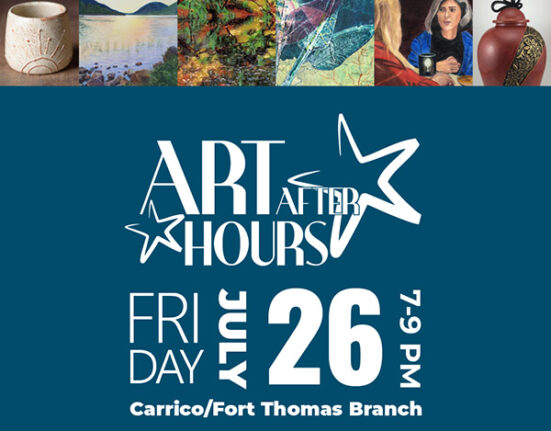

Justin Bateman, Pablo Picasso

Photo courtesy of Justin Bateman

What do you like about the ephemeral nature of your artworks in forests or on beaches?

Embracing impermanence began as a test of my own spiritual practice, letting go of my personal belongings to travel. But later, it became the most appropriate way to maintain the natural environment whilst making art. When I visit the forest or beach, I don’t want to see signs of human presence. I prefer to feel the closeness of nature and observe the networks of evolution, leaving no trace of my presence. You might call my work photography because without a photograph, it would remain esoteric, witnessed only by the very few who see it on location. This is rare because I increasingly choose remote locations, even when working in urban areas. Many people are frustrated by my work’s impermanence, but just as the Tibetan monks blow their sand mandalas into the ether, I have become very accustomed to its ephemeral nature. I should mention that I do create permanent work too, but the majority of my work remains impermanent and I like it that way.

Take me through your creative process. How do you choose the sites for your works and where do you source the stones? Do you assemble your artworks in your studio first or directly on site? Which comes first: the stones or the subject matter?

Once an idea has developed, my mind automatically seeks locations and the correct “stonal” values to bring it to life. It happens very naturally; an invisible filter is applied to the world. I will start to notice locations that have a great backdrop or add context to the work. If the work wants to be made, I will stumble across the exact gradient of stones I require; I don’t have to make many decisions consciously. The more cerebral part is the technical processes. I develop color maps using anywhere up to 16-bit images. I study the maps for their values, collecting enough stones to finish the piece. Depending on scale and complexity, the stone collection alone can take weeks. I love to collect stones from lots of places on walks and hikes, but I am careful where I take them from. Quarrying is illegal and I never remove stones from conservation land. Most of the stones are found at the location where I work. Once I have the materials, I do some tests, usually starting with the eyes to see if I can capture their character. If the eyes don’t work, the piece cannot be made. They do seem to be the window to the soul. Making the work is less meditative than collecting the stones. Sometimes it is straightforward, but if the stones are misbehaving it can take many weeks. It commonly takes between five and seven days. If the site is remote enough and weather allows, I make the work then and there, returning day after day. But if there is footfall nearby or meteorological challenges, I will make the work at my studio, then carry it to the location. The work is unfixed and fragile, so this can be a challenge of both dexterity and strength requiring some extreme choreography!

Justin Bateman, Cherub (after Raphael)

Photo courtesy of Justin Bateman

Follow me on LinkedIn.