The works of Irish artists Ciarán Murphy and Niamh O’Malley couldn’t be more dissimilar at first glance. Murphy specializes in dreamy and melancholic paintings, while O’Malley uses materials like steel, limestone, wood and glass for her sculptural installations. But despite their differences, the two share a similar goal—creating art amid chaos.

Later this month, the unlikely duo will present parallel exhibitions in New York. The project is one of many benefiting from a new round of government funding in Ireland that aims to globally boost Irish artists in the fields of visual art, literature, theater and even the circus. Nearly 3 million euros ($3.2 million) is being utilized by government agency Culture Ireland to promote programs and institutions abroad, as announced last month by Catherine Martin, Ireland’s culture minister.

The show will take place between Dec. 15 and Feb. 17 at the Tribeca outpost of the Amsterdam-based Grimm Gallery, representing Murphy’s second solo exhibition with the gallery in New York and O’Malley’s debut show in the U.S. A series of new paintings will make up Murphy’s presentation of “still, weight, thing, a title which acts as a pun on the phrase “still waiting.” The play on words is “hopefully a parallel to what some of the work tries to point out,” Murphy told Observer.

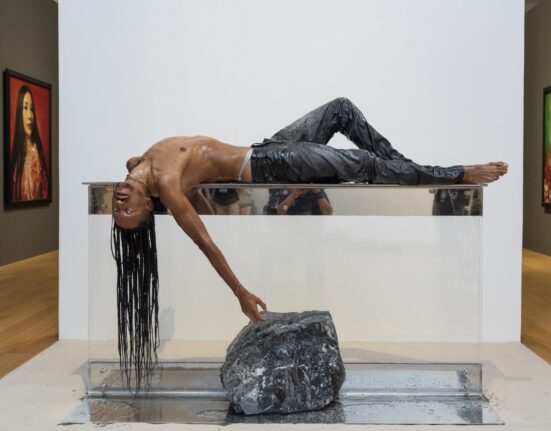

O’Malley’s exhibition “Lightbox,” meanwhile, will bring together sculptures building on Gather, her presentation for the Irish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennial in 2022. Representing Ireland at Venice allowed O’Malley to make work “of a scale or a kind of ambition that I hadn’t done before,” the Dublin-based artist told Observer.

The shows will open in tandem at Grimm’s location on 54 White Street later this month. The idea of presenting such contrasting styles of artwork in a two-person show “immediately struck me as an interesting possibility,” said Murphy. Ahead of the upcoming exhibitions, Observer caught up with Murphy and O’Malley to discuss their artistic processes and how they find inspiration.

Could the two of you tell me a little bit about the work you’re going to show later this month in New York?

Murphy: I feel like it’s an extension of, like most artists, what I’ve done before. As an artist, you want to make the next show have some coherence with what you’ve done in the past but also maybe develop it in certain ways. Some of the scale of the work is bigger, for example.

But one thing that I do in a kind of a general sense of my work, like a lot of artists who work with painting and images, is trying to negotiate making images in a very saturated image economy. It’s quite a paradoxical state where images are omnipresent everywhere, but they’re immaterial, fleeting; so they have this kind of ghostly presence.

O’Malley: I’ve been making a lot of very big work recently because I’ve had some larger public shows, but for this show, I’ve made some new smaller pieces, which has been really nice—partly, to bring it back to the body really closely.

In this show, there are these large-scale kind of parentheses, which physically bracket the room but also maybe create a space within them of the architecture of the room. And then the smaller objects, I like to think of them as phrases or sentences in the space that could be moved through, like they’re all carrying their own weight of their materiality, their production history, their sense of touch, the hands that have made these material forms that they are constituted from.

Ciarán, I know you start your works by putting together collages of spliced photographs. Why and how did you start using that technique?

Murphy: For me, chance is very important in a studio. And collage gives us a way of coming up with juxtapositions that are surprising and not intended. So for almost every image in the show, say the ground might have been started and left for maybe sometimes years, and then I get the idea to put something there because it happens to fall in place. It’s not total chaos; I have systems in place with lots of cut-out bits I can rearrange.

I recently read a wonderful description of our contemporary mediascape as “an animated collage,” and I really liked that idea. The idea of a fractured kind of reality has been familiar for quite a while now, but I think it sums up that paradox where an animated collage is things delineated from each other, yet it has this kind of coherent syntax or something like that. I guess I’m kind of playing with that.

Niamh, how did this being your first show in New York City change the way you thought about the work?

O’Malley: There’s a lot of things in the show that are thinking about how we form urban environments to work for us and how we always push it that little bit further to make them more than that.

There’s a very large stone drain piece which is limestone from Ireland and is going all the way to New York. Limestone is compressed seabed, so it’s come from

As Irish artists, is there anything that stands out to you in terms of the differences between the art worlds in Ireland and the U.S.?

O’Malley: Scale. It’s very tiny in Ireland. And we actually function kind of outside of the market, which is quite interesting. There’s a large and supportive public system here, with grants for artists, museums and galleries are free, and there’s an opportunity to show publicly for even younger artists. There’s kind of a different sense of art’s place.

How do you like to approach what work you want to explore next?

Murphy: Often I find I can’t really see the work until I’ve actually installed it, and then there’s things that I haven’t noticed in the studio at all that give me ideas for where to go next. Certain paintings that read off each other or works that I might not have liked so much shine in certain contexts. That’s where I kind of take my cues from.

O’Malley: The work doesn’t complete in a sense until it’s hung and activated by an audience, and I don’t think people account for that enough. For us to see the work in the space and out of the studio context—that’s what triggers the next paths and the conversations that will happen.