Yu’s black humour is often in evidence in her somewhat disturbing images. The altarpiece, ironically titled Make a Wish (2023), is a tall panel fitted into the original, Baroque altar.

It depicts faceless individuals crouching, their hands bound or placed behind their heads, prisoner-style; two bare-chested men either fighting or in a passionate embrace; and two women plunging through the empty, golden background like fallen angels.

The work is Yu’s response to a 1607 altarpiece by the Italian painter Caravaggio, called The Acts of Mercy, that depicts seven acts of kindness within a single frame.

Her version depicts scenes she has seen from news photos, such as that of a woman jumping off a building before she was, thankfully, rescued.

Flanking the work is a monumental 10-panel series called Walking through Life (2019-22). Again, these are in the style of Byzantine icons with their golden backgrounds, but with the images of Mary, Jesus and saints replaced by images taken from social media.

Arranged in a semicircular arc, this painted cycle of life begins with a bloody newborn on top of its naked mother, and ends with a stack of seven cadavers with only the feet showing: at the top, the unmarked, tender soles of an infant and at the bottom the gnarled, deformed bound feet of a woman.

The scenes in between show moments of cruelty and absurdity, such as young children being trained to become contortionists, or a group of women trying to lose weight by wrapping themselves in cling film.

There is no heroism here. The sense of eternity conveyed by the iconic format suggests that humanity will forever more be trapped in its foolishness and fragility.

On the other side of the space is a 9-metre-wide triptych of a sublime landscape. Against a flaming sky, a group of children are clambering onto a boat as icebergs melt and crows circle overhead.

Their perilous future in the face of climate change is made more dramatic by the wild, loose brushstrokes of the waves and the unsettled sky.

Is there hope? “Everyone seeks some form of salvation, and I believe it should arise not only from divine sources but also from within ourselves,” the artist says.

Yu, born in Xian, western China, in 1966, is well known for her figurative paintings that often foreground the experience of women in contemporary China.

A graduate of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, she has adapted the official Socialist Realism style that she was trained in not to glorify, but to capture, often-neglected quirks and the fallout from rapid change in society.

Yu says she is thrilled by the final installation of a project that has taken several years to bring to fruition. The exhibition is presented by the Asian Art Initiative of the Guggenheim Museum, New York, and curated by Alexandra Munroe, senior curator, Asian art and senior adviser, global arts, for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Yu explains that the Chinese exhibition title “Tumbling in the Dust” was used by the writer Lu to describe the political reality of the early 20th century, but she finds that it is still an apt description of the state of the world today.

“Whether in China or elsewhere, life is a struggle in the dust, either consciously or forcibly, until returning to dust in the end,” the artist says.

Her choice to incorporate news photos taken from the internet has to do with a wish to reveal the “truth” of humanity today.

“The ideas behind these large-scale paintings date back many years; they gradually took shape over time. For the multi-panel works, because of limited [studio] space, I completed one canvas at a time and only got to see the full effect of them being shown together when I came to the exhibition myself,” she says.

Deep inside, you are always an outsider without a sense of belonging

Yu tells the Post that the setting in Venice conveys “a profound sense of time” and the tradition of religious art essentially conveys humanity’s age-old “contemplation of the ultimate questions of life”.

“Because of the lack of a sense of security, humans often set up barriers, label people according to criteria such as distance and closeness, and divide them into different levels of ‘insider’ and ‘foreigner’.

“In this turbulent and uncertain era, discrimination and hatred towards immigrants, refugees, different races, identities and genders have brought enormous conflicts to the world.

“Wherever you go, you will encounter ‘foreigners’, and may as well become a ‘foreigner’ yourself.”

She adds: “No matter where you are or how you struggle in the dust, deep inside, you are always an outsider without a sense of belonging.” Hence her vision of bodies being flung through space like dust caught in a breeze.

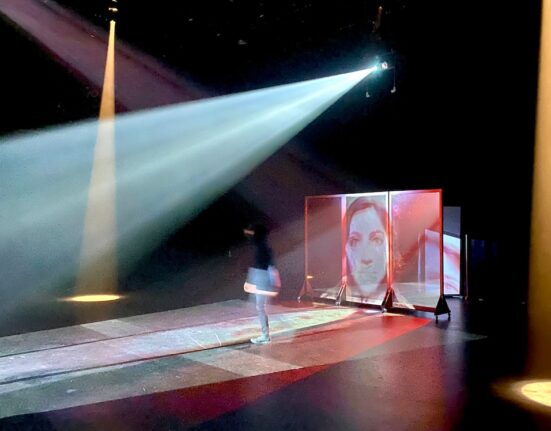

On June 6, US contemporary classical music composer Nico Muhly will present the world premiere of the immersive soundscape To the Body (2024) at the Chiesetta as a meditation on Yu’s Walking through Life (2019-22) along with the Danish composer Dieterich Buxtehude’s 1680 cantata Membra Jesu Nostri, each section of which focuses on one of Christ’s seven wounds on the cross as described in the Bible.

Inspired both by Yu’s paintings and the former church’s atmospheric space, the musical work, which the artist describes as “medieval, ethereal and very contemporary at the same time”, will play in 10 sections without pause, and repeat seamlessly as fragments of Buxtehude’s cantata appear, deconstructed from its original context to both complement and serve as a counterpoint to Yu’s exhibition.

A live performance of To the Body will be staged at the Guggenheim in New York on November 10.

“Yu Hong: Another One Bites the Dust”, presented by the Asian Art Initiative of the Guggenheim Museum, New York in the Chiesetta della Misericordia, Campo de l’Abazia, 3550, Cannaregio, Venice, Italy. Open from Tuesday to Sunday. Summer hours: 11am to 7pm until September 29; autumn hours: 10am to 6pm until ending on November 24.