NEW YORK — Two photographs caught my eye at (In)directions: Queerness in Chinese Contemporary Photography, a group show at Eli Klein Gallery through the end of the month. In Alec Dai’s “My Jet Black Hair” (2021), two figures of indeterminate gender appear to rest upright on each other, not quite in embrace and not quite in repose. Their black hair intertwines. The foreground figure faces away from us, their back exposed. In “Pot Fisting” (2021), an arm with a snake tattoo holds a blue and white porcelain teapot by its spout, while an arm with a tattoo of what looks like an antique Chinese chair dives deep into the body of the pot.

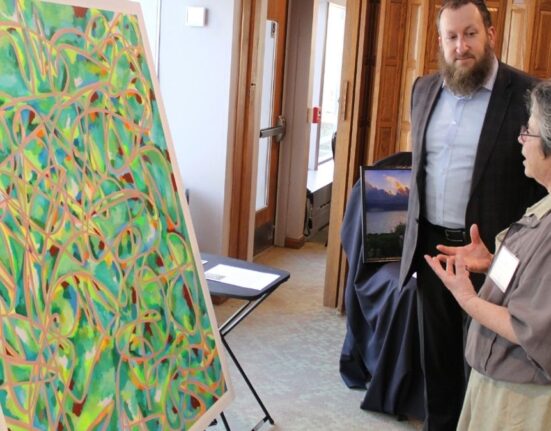

Quirky (or should I say queer?) juxtapositions add to the character of the exhibition, a captivating collection of 21 artists exploring “queerness as a possibility, embracing the imaginative even when the status quo might otherwise be limiting,” as the exhibition text notes. This sense of possibility shows through figuratively in Yang Bowei’s “Caged Butterflies” (2017), a black and white image of the insects in clear containers. Installed just above is the artist’s “Symbolistic Father” (2017), depicting a figure resting on what looks like a bed, a hand caressing the back of their head.

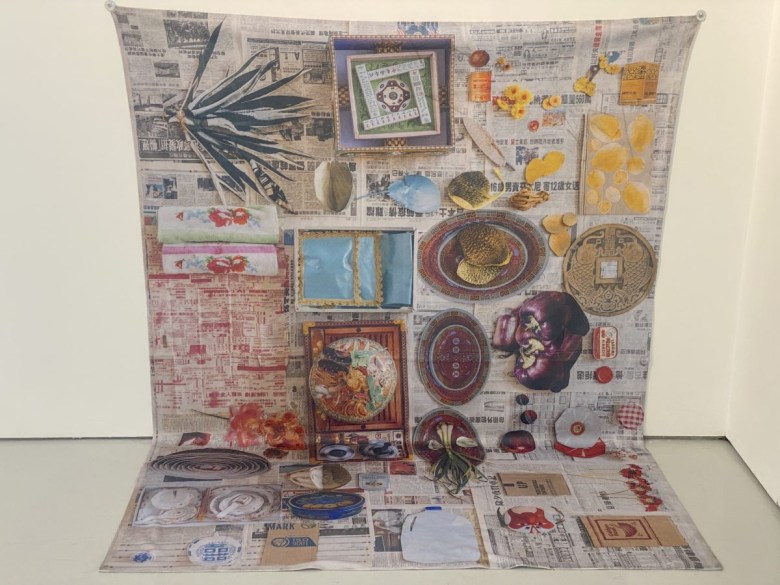

Other works queer the way we display photographs. Artist Tommy Kha’s “Article I” (2022–23), made from dye sublimation on fleece, features slices of fruits and vegetables, pieces of cardboard, a can of sardines, and other objects arranged on newspaper. The fleece is hung low on the wall so it folds at a 90-degree angle against the floor. And in Kha’s photograph “Stops (III), Oneonta, NY” (2020), 10 hands reach out from the ground in a lush green field, presumably in the work’s eponymous city. Once again, the photo and frame are installed at a 90-degree angle, this time on the corner of a wall.

The body, the site of so much exploration, trauma, and joy in queer identity, appears frequently. Pixy Liao’s “Long Sausage” (2016) shows two figures in short shorts, one feminine, the other masculine. The masculine figure caresses a long sausage protruding from the feminine figure’s groin. It’s placed on the same wall as Shen Wei’s “Daisies” (2022), in which a nude masculine figure rests prone in a field of daisies, their perineum visible. Liao’s “Breast Ass” (2019), installed nearby, pictures a nude figure bending over and holding fake breasts over their buttocks. Just below is Shen Wei’s “Bonsai” (2023), where a nude figure bends over in a rooftop garden to yank a bonsai stem.

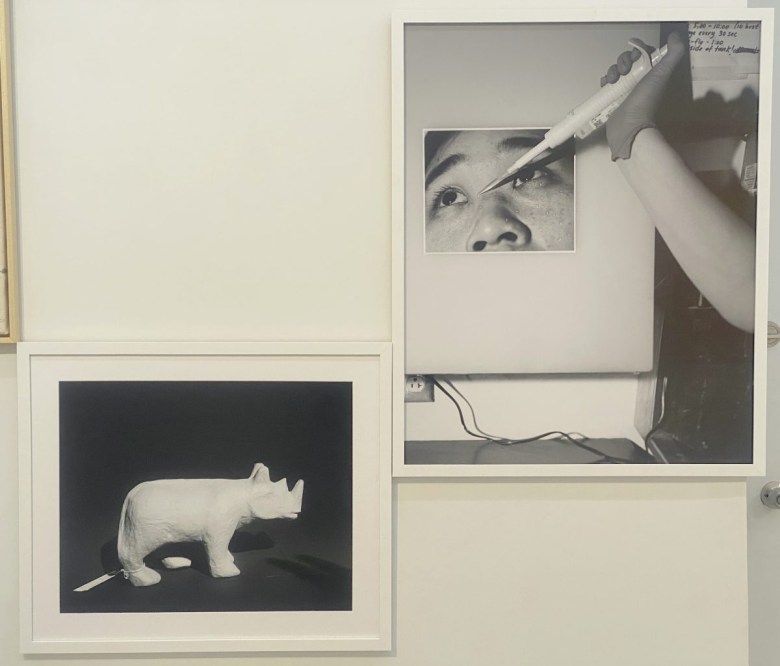

My favorite juxtaposition is Kanthy Peng’s “Artificial Tear” (2019) alongside the artist’s “A Rino Labeled Gay #4” [sic] (2023). In the former work, a hand wearing a latex glove and holding a large syringe drops a tear on a photo of upward-gazing eyes. In “A Rino,” a white clay rhinoceros figure has a tag on its back right foot. It probably doesn’t need the label, but it has one anyway. Throughout the show, queer identity is questioned more than defined, and these works in particular made me think about the identities we can and cannot adopt and tears we can and cannot shed. If straightness implies direction, queerness suggests anything but.

(In)directions: Queerness in Chinese Contemporary Photography continues at Eli Klein Gallery (398 West Street, West Village, Manhattan) through January 31. The show was curated by Phil Zheng Cai and Douglas Ray.