On View

Dallas Museum Of Art

He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject

December 17, 2023–July 21, 2024

Dallas, TX

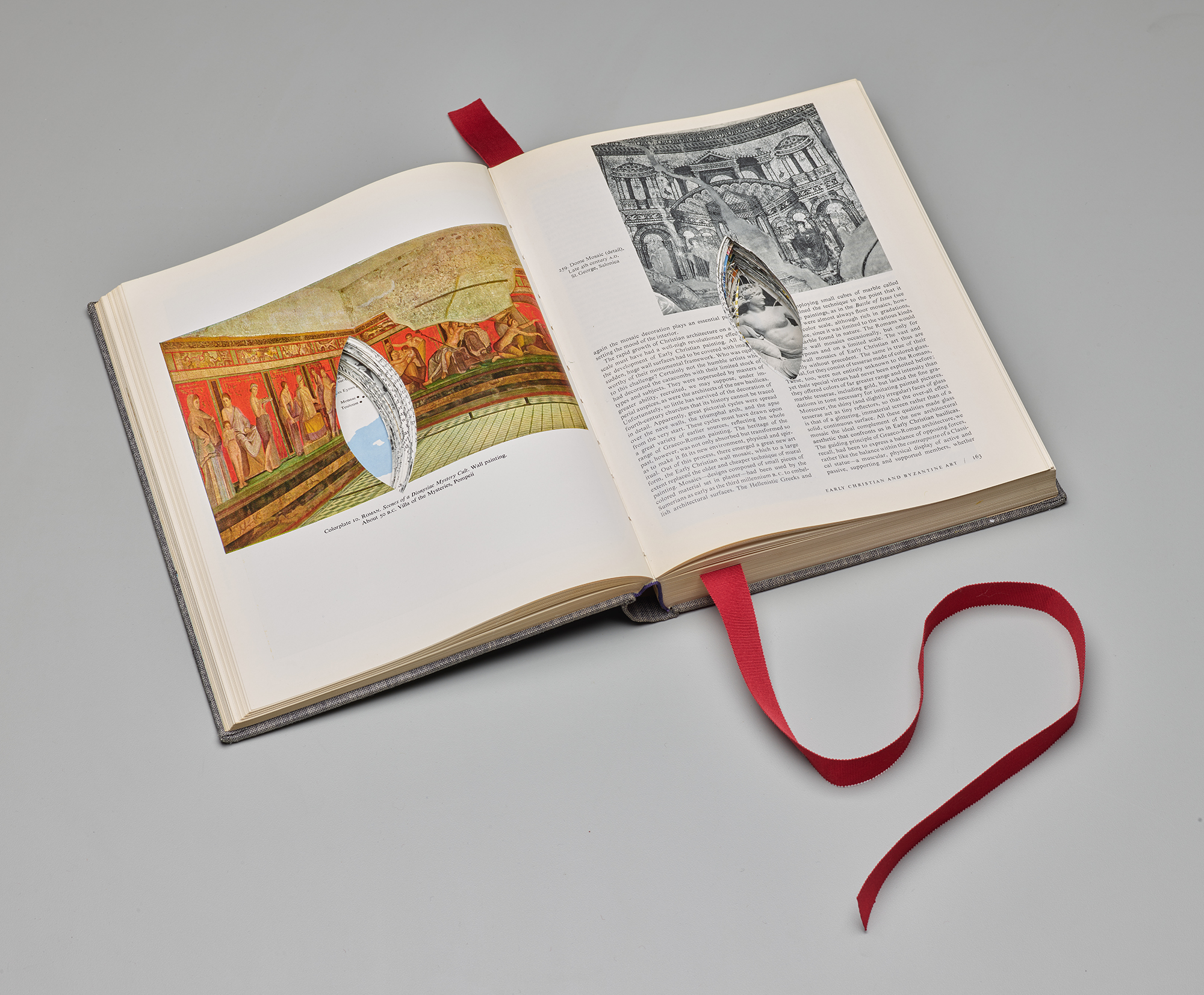

An aged and mutilated textbook sets the tone for He Said/She Said at the Dallas Museum of Art. Kaleta A. Doolin has carved a vulva-like orifice through H.W. Janson’s art history tome; a Neoclassical nude woman, Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (1805-8), peeks through the now-tunneled core of History of Art. Doolin’s Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page (2018) felt like a promising conceptual start to an exhibition that had all the marketing makings of a feminist affirmation. Janson’s History of Art originally excluded women artists, an informational placard tells us, but contains plenty of naked women, suggesting that we were about to enter a landscape of overlooked talent and influence. But He Said/She Said is not primarily concerned with the undocumented female contributions to artistic development; rather, it is interested in appropriation.

Doolin’s Improved Janson rests quite literally beneath the shadow of Jackson Pollock’s Cathedral (1947). Alongside Cathedral are two works from women artists: a polaroid drip by Sarah Charlesworth and an installation and video of one of Carolee Schneemann’s performances. From here, it becomes quickly clear what the curatorial approach of the show is: present us with supposed male genius and attempt to take it down a peg. Charlesworth’s Yellow Action Painting Photo #3 (2006) pushes against the assertion that the splatter work of Pollock cannot be replicated by depicting a splatter using photographic print, an inherently replicable medium. In Schneemann’s Up to and Including her Limits (1973-6), appropriation takes the form of a challenge, engaging with the physicality of action painting as seen in the accompanying video documenting the artist’s harnessed process. Across the gallery, two mammoth canvases hang side by side: Jasper Johns’s Device (1961-62) and Deborah Kass’s Making Men #3 (1992), her piece a collage of references to male artists including Johns and David Salle, both of whom deployed appropriative techniques in their own work, as well.

The initial atrium spills into a second gallery space, sunken and expansive. This room also holds famous works by famous men (among them Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108 [1966], referred to in Kass’s piece), who appear most prominently in the section “Black Female Subjectivity.” Here, works by Black female artists are shown alongside the objects by the white male artists they are confronting.

One of the most powerful pieces within this section, Lorna Simpson’s ink and watercolor screen print Blue Turned Temporal (2019), is presented without its referential male work (beyond a small image on its placard of Frederic Edwin Church’s The Icebergs [1861]). This allows the viewer to absorb it without a peripheral work taking up its oxygen. Blue Turned Temporal is indigo and ghostly and emits the sort of overbearing and frightening sense of adventure that comes with arctic expeditions. Here, appropriation is not used simply as a mimic or warping of styles, but as a commentary on the exclusion of Black people as heroic subjects and artistic protagonists. Nearby, Lauren Halsey and Janiva Ellis are situated alongside their appropriative marks, Donald Judd and Robert Motherwell, and once again we seem to have returned to a game of compare and contrast.

Strangely, in the gallery’s sister section, “Women and Appropriation,” the referenced works are more absent. Here, the art seems to stand alone, some placards contextualizing their inspiration (Sherrie Levine’s After Man Ray (La Fortune): 6 [1990] after Man Ray’s La Fortune [1938]), some avoiding the subject of appropriation altogether (Dracula and the Artist [1991/2019] by Lorrain O’Grady) and some with no curatorial commentary (Joyce Pensato’s Felix [2007]). Suddenly, the thread seems a bit vague.

Barbara Kruger’s Pledge, Will, Vow (1988/2020), which is situated as the centerpiece of the gallery, is one of the pieces which avoids the subject of appropriation in its wall text. It is also perhaps the most arresting of the show, a digital installation which distorts the Pledge of Allegiance, marriage vows, a last will and testament. It lingers with you, both emotionally and audibly, a click-click-clacking filling the air as you move into the back gallery. There are many works in He Said/She Said that are excavating ideas beyond appropriating male artists, yet they are obscured beneath its veil.

Relief from my growing struggle with He Said/She Said’s thematic approach came from the unassuming corner of the back gallery, “Women in Surrealism,” hosting Leonora Carrington’s Tiburón (c. 1942) and Max Ernst’s The Bird People (1942). Here, the corresponding text acknowledges Carrington’s frustration at her prolonged association, both stylistically and personally, with her former lover, Ernst: “Those were three years of my life! Why won’t anyone ask me about anything else?”

What or who do we worship in He Said/She Said? This exhibition begs us to question the assumption of male genius by pointing us toward female artists and their power of appropriation. Is it used to undermine or poke fun at “male genius”? Is it to improve upon it? Is it questioning origin stories? In this exhibition, appropriation is many things (as it so often is) but a nugget that felt more scintillating was the sentiment of appropriation as a form of commentary, but this is admittedly the hinge I am still turning over in my mind.

He Said/She Said stumbles within the entanglement it attempts to undermine. But while it does not achieve a sort of feminist perfection, it wades into the waters and attempts to dismantle the inflated reverence of male genius. An expectation that every excavation or curation or manifesto or social media post dismantling patriarchy must be wholly and impenetrably valid, inspiring, revelatory sets us all up to fail. Is He Said/She Said the final word on female artistic genius? No. Is it imperfectly worthwhile? Yes.