The HR executive’s gaze fell on 34-year-old Yeung. “What’s going on with her hands?” she asked, as if Yeung had not been in the room.

Lam, who uses the pronoun “they”, says their blood boils just thinking back to the interview. “‘Er, she doesn’t have hands,’ I said. That was obvious,” Lam recalls.

The interviewer turned her head away and said: “We don’t hire people like her.”

Yeung lost both her arms in an accident in Guangzhou, in China’s Guangdong province, when she was nine years old. She was playing on a rooftop when an electrical leakage damaged both her arms, which needed to be amputated. She moved to Hong Kong to attend a special school for disabled children.

In secondary school, Yeung represented Hong Kong in swimming at the 2010 Asian Para Games in Guangzhou. She later switched from sport to focus on art and graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in fine art from Australia’s RMIT University. But she found painting very restrictive.

“So I started to do installation and performance work. It is more immersive, so people feel the intensity of the art. I didn’t have any difficulty entering the art circle, it is an open-minded community. Art is diverse and inclusive,” Yeung says.

The unfortunate job interview marked a turning point. The interviewer ended up slamming the table and saying she did not want to discriminate against Yeung, but that no one would hire her.

“Everything she said was discriminatory,” says Cheng, who identifies as queer. “In that moment, we realised that in cultural and art circles we appreciate people’s differences. It is OK to be unique there. But in the workplace, they just want everyone to excel in their job. They don’t want differences.”

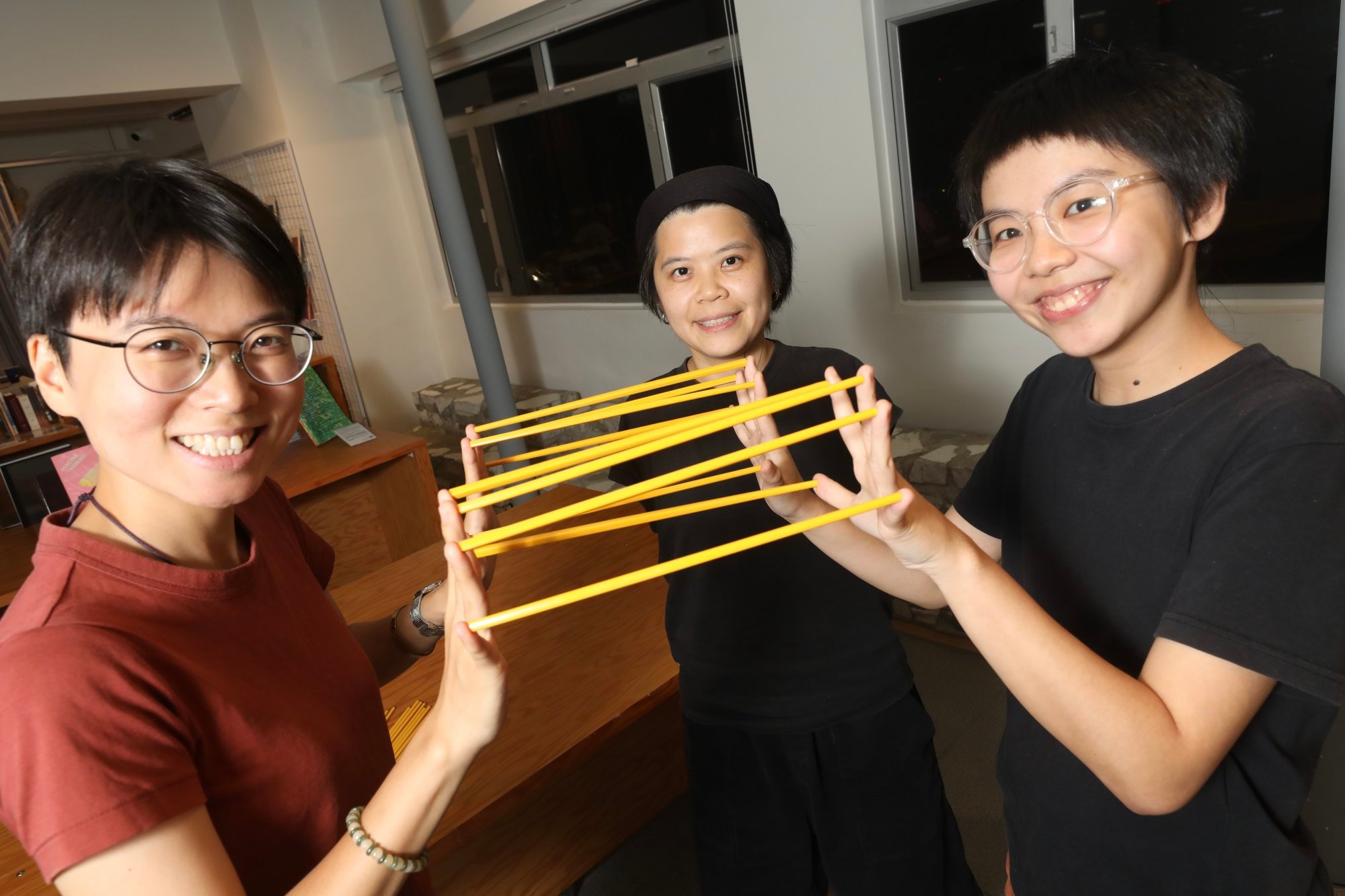

Since 2022, their collective c.95d8 – the name comes from Hong Kong slang meaning irrelevant, random nonsense – has hosted public events in their Sai Kung space and ran a LGBTQ film screening marathon during Pride Month in June 2023.

After the job interview, they came up with a bold proposal to “crip” contemporary art: to bring the experiences of disabled artists to the public arena and foster a truly inclusive art ecosystem.

Don’t call people disabled any more, call them ‘crip’. Disabled means not able … I think crip has more attitude and possibilities

The collective launched a separate “crip art residency” through an open call. It will exhibit works by artists made during the residency as part of Eaton HK hotel’s “Eclipsed Bodies, Embraced Pride” queer arts and cultural programmes, which the hotel launched on May 31 to celebrate Pride Month in June.

Three artists in the c.95d8 residency – Chan Mei-tung, Jessica Chiu and Nora Fong – will display their work in Tomorrow Maybe, the art space on Eaton HK’s fourth floor, from July 4-16. Entry is free. The collective has also invited two overseas artists to speak at Eaton HK: Jeremy Hawkes, an Australian crip artist, and Janet Tam, the former director of the Arts with the Disabled Association Hong Kong, who is now living in the UK.

In the West, “crip”, a term historically used as slang for “cripple”, has been undergoing a process of reclamation by the disabled community.

“Don’t call people disabled any more, call them ‘crip’,” Cheng says. “Disabled means not able, but we don’t think they are not able. I think crip has more attitude and possibilities.”

Lam, who has gender dysphoria and is involved with some transgender groups, sees overlaps between LGBTQ and crip identity.

“Queer is rejecting the oppression of heteronormative society. And crip is rejecting the ableist society. Both can go together. I want to embrace both queer and crip,” Lam says.

To render “crip” in Chinese, c.95d8 has adopted an element used in the character for “damaged” that is also used in many other words, to express diversity of understanding and the “infinite potentials amongst imperfections”. That element is also the 43rd hexagram of the I-Ching – an ancient Chinese divination text – in which it means “determination” or “breakthrough”.

“We finally have our own translation of ‘crip’. It’s like queer, it’s an identity,” Lam says.

“We are bringing this term to the Asian context. By using a character from the I-Ching, it is a more neutral word. It is a beautiful word because we don’t combine it with different characters.”

For the trio, embracing “crip” identity feels liberating – a chance to be unapologetically themselves.

“In terms of diversity, equality and inclusion, Hong Kong is still very far behind,” Cheng says. “In addition to embracing queer identity, I can embrace crip identity because it feels more releasing. I can be more myself.”

“Crip – An Exhibition”, Tomorrow Maybe, 4/F Eaton HK, 380 Nathan Road, Jordan, July 4-16, 11am-9pm. Opening reception and live performance by Chan Mei-tung, July 4, 7.30pm; closing and live performance by Jessica Chiu on July 16, 7.30pm.