“A chocolate city is no dream,” bandleader George Clinton said on the album’s title track. “It’s my piece of the rock and I dig you, CC.”

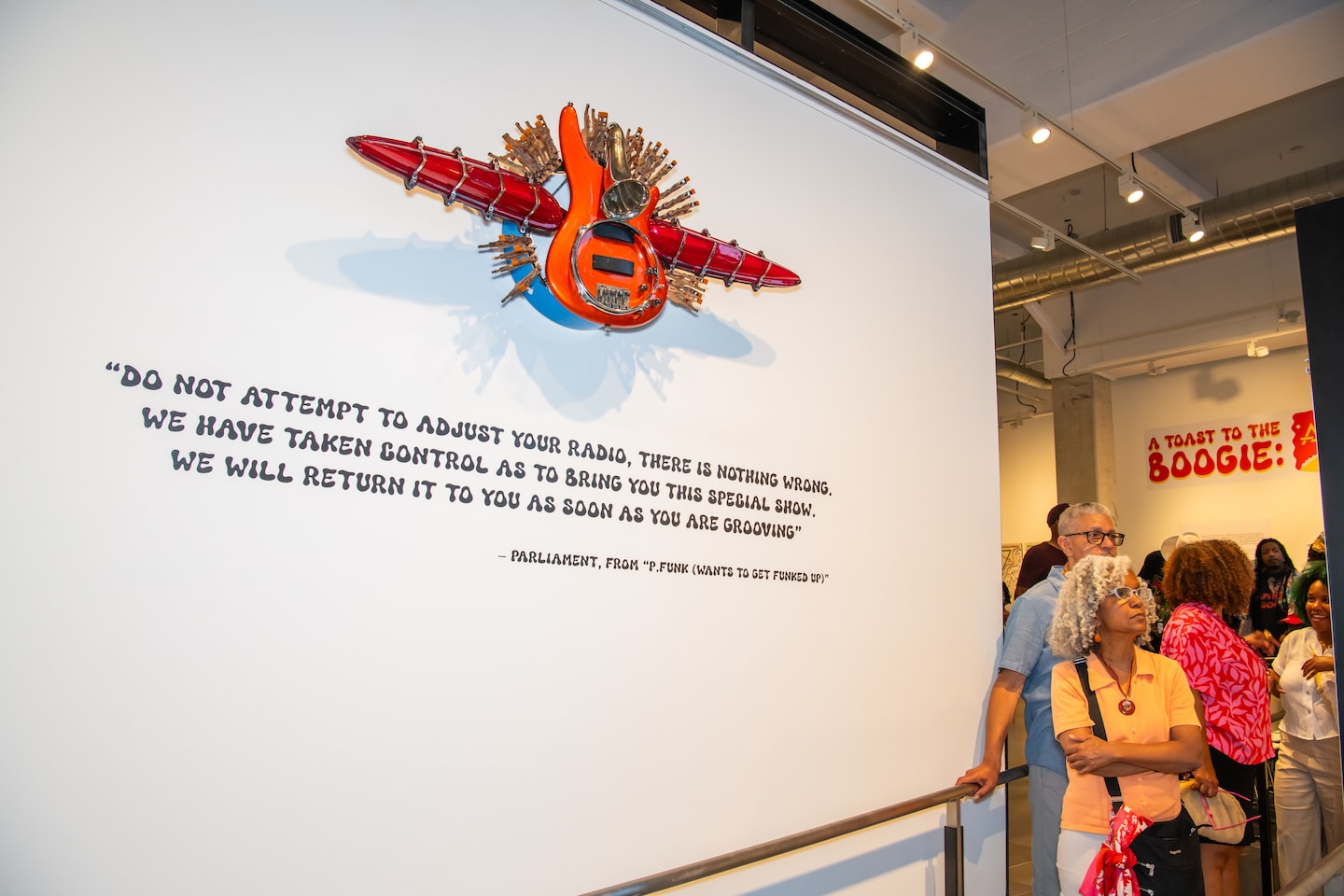

Nearly 50 years on, the city is cementing its mutual appreciation with “A Toast to the Boogie: Art in the Name of Funk(adelic),” a collection of original artworks and archival material that celebrates the persistent impact on art and culture — especially in D.C. — of Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic.

“Chocolate City has always shown the family and the band love,” said curator Michelle May-Curry. “It just felt like the right place to begin to explore this family’s collection.”

And the prime minister of funk himself showed up to mark the occasion.

“A Toast to the Boogie,” on display now through Aug. 16 at the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities’ I Street Gallery, brings together two threads: the Clinton Collection, composed of never-before-seen photographs, memorabilia and artifacts shared by the wider Clinton family, and a juried exhibit that includes works from 20 visual artists that demonstrate the continued legacy of P-Funk’s visual language.

“I really wanted to display the variations and the versatility that the artwork had throughout the years,” said Zavier Croft, the exhibition’s co-curator and Clinton’s grandson. “It wasn’t only pictures, illustrations and photographs. … I really wanted it to be a whole visual aspect.”

Along with Croft’s collection of album sleeves and the original “Cosmic Slop” test pressing, the Clinton Collection includes candid backstage and family photographs and issues of the band’s proto-zine New Funk Times that bring the outsize P-Funk universe down to earth. The juried exhibition also includes concert photography by Tom Terrell, a ubiquitous figure in D.C.’s music scene in the 1970s and ’80s who also wrote liner notes for a reissue of “Chocolate City.”

“He really loved Funkadelic, he loved George Clinton. He loved the style, and he liked bringing new music and new groups to people — that was his calling card,” Bevadine Z. Terrell said of her brother, who died in 2007.

Some of the exhibition’s strongest inclusions are pieces that show how the band’s aesthetic has influenced artists over the years, such as a section that brings together the art of two D.C. natives: P-Funk album artist Ronald “Stozo” Edwards and outsider artist Mingering Mike, who created his own fictional musical universe that has been collected by the Smithsonian.

“One of the things we wanted to do with this exhibition is show how many artists were explicitly in conversation with the album artwork and the P-Funk universe, but then also used the aesthetic of the album artwork to make their own work,” said May-Curry.

And while Clinton and P-Funk are perhaps best known for stages full of costumed musicians, psychedelic antics and timeless party-starters such as “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker)” and “Flash Light,” the collective also translated a tumultuous decade into rich musical metaphors, from the explicit (“America Eats Its Young”) to the poetic (“Maggot Brain”).

“You think about the crazy colors and drugs, but they were really politically focused and spoke about different issues that they experienced, that the world was experiencing,” Croft said. “You can listen and say, ‘Holy crap, we’re still going through this now.’”

The political aspect of the P-Funk experience is captured in several pieces in the exhibit, including Anna U Davis’ “On Top,” a striking black-and-white cutout of a Black woman, with afro and knee-high stilettos, chained to the Washington Monument, or Jet Carter’s “Motherboard,” which sees the Mothership hovering above the White House and go-go drummers set up outside the gates.

The Mothership — itself a featured item at the National Museum of African American History and Culture — looms large in the collection, representing P-Funk’s influence on what would become the Afrofuturism movement. Roderick Turner’s “SG20 (Solid Ground 20/20 Vision) Series” is a collection of shadow-box sculptures that imagine the funky creations of a scientist ambassador. Auguster Williams, showing art in a gallery for the first time, contributes “Aboard the Funkadelic Star Ship (FSS) Pedro Bell: Boogie in the Black Hole,” a mixed-media collage that imagines the mothership from above.

“A Toast to the Boogie” grew out of a relationship between Melvin Witten of the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities and Tonysha Nelson, Clinton’s granddaughter and a musician who works with her grandfather on- and offstage. Nelson says she is overwhelmed by the exhibit and the love that flows through the celebration of Parliament-Funkadelic.

“He’s my superhero, and I’m very proud to call him my grandfather,” Nelson said. “I’m happy that people see him as the hero that he is.”

Even at 82-years-old, Clinton is still funkier than most people can ever hope to be. On Tuesday, he showed up for a news conference and gallery tour wearing a bucket hat, a “Cosmic Slop” hockey jersey and multicolored sneakers. But he remained relatively quiet.

On Wednesday, swapping out the jersey for a pearlescent cloak and appearing during a panel discussion about protecting the arts, he was in fine form. Speaking for about 15 minutes, the living legend reeled off the abstract poetry of P-Funk lyrics, shared wisdom about contemporary music and delivered the swagger that has made him an icon for half a century.

Looking back at the beginnings of Parliament-Funkadelic, he recalled how, in the post-Motown era, “you could be as cool as you wanted to be.”

“D.C. — Chocolate City, CC,” Clinton said during the discussion, “To talk about this here is really fun, because this is where we actually got the nerve to do it.”