Stroll past the cafés and boutiques on Shabazi Street in Tel Aviv’s trendy Neve Tzedek neighborhood and it’s hard to miss the ever growing number of contemporary art galleries with their colorful pop art, Warhol-inspired portraits and rows of acrylic diamond-studded Mickey Mouse sculptures.

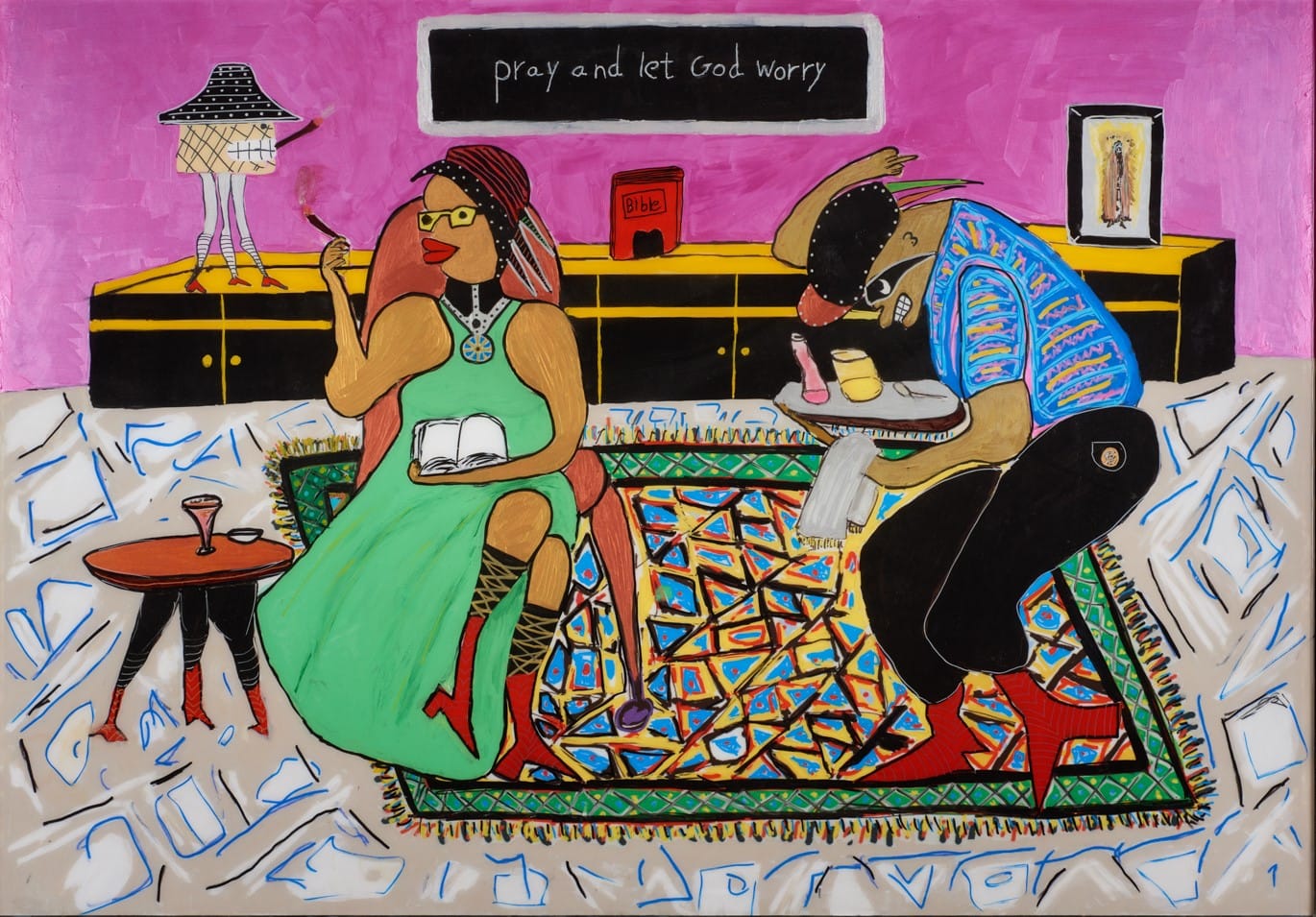

Then you get to Shabazi 58, where the works juxtapose street style with traditional African motifs and seem far more suited to an edgier artistic environment.

Moshe Tarka, the Ethiopian-born multidisciplinary artist and social activist behind the space, says his choice of the unlikely location was intentional.

“Opening in Neve Tzedek was an act of art itself. I want people to be exposed to something different, to ask questions, to really understand. It was an act of breaking the glass ceiling as a Black-Jewish-Israeli artist.”

Another goal of Shabazi 58 was to steer a new generation of Ethiopian Israeli artists away from being perceived as creators of mainly decorative art.

At a recent Sigd (Ethiopian prayer festival) event, emerging Ethiopian artists presented works of sculpture, photography, video, dance and music.

“This gave them a platform. I want our Ethiopian community to be understood and to succeed in Israel,” Tarka tells ISRAEL21c.

The plan to have the space open for only three months has now stretched into three years, with crowds regularly attending performance art events and gallery talks organized by Tarka, 40, and his French-born wife, Rebecca.

And although he says sales were never a goal, Tarka’s works now fetch thousands of dollars. They can be found in private collections in Israel and abroad and have been exhibited in major museums across the country.

From Ethiopia to Israel

One of eight children, the artist was three years old in 1984 when his family was brought to Israel via Sudan in Operation Moses.

The family was settled in Kiryat Arba, where religious Zionism was dominant and although they didn’t experience racism, “there was no real emphasis on their Ethiopian identity either.”

Tarka’s mother sculpted and his older brother dabbled in artistic activities, but art was not part of their lexicon, he explains.

“Art in the community was decorative. They didn’t understand my abstract work in large formats and would ask ‘Where is the tradition?’ So I would do art for myself, on impulse, and then throw it away as I was embarrassed by it. I didn’t think of myself as an artist.”

Then in 2008 at the age of 24, while he was living in Ashdod, Rebecca (then his girlfriend) entered him into the visual arts category of the city’s Young Artist competition. Tarka won first place and “everything started from there.”

On the panel of judges was prominent Israeli curator and Israel Prize winner Yona Fischer. Fischer, who was known to discover and nurture artistic talent, took Tarka under his mentorship and for the first time Tarka started to view the work he was doing “as art and not something strange.”

With this newfound confidence, Tarka applied to study fine art at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem and the industrial design program at Sapir College in Sderot.

He was accepted to both, but decided on the latter on the advice of Fischer, who warned formal art studies would “destroy” something in the developing artist’s work.

Exposed

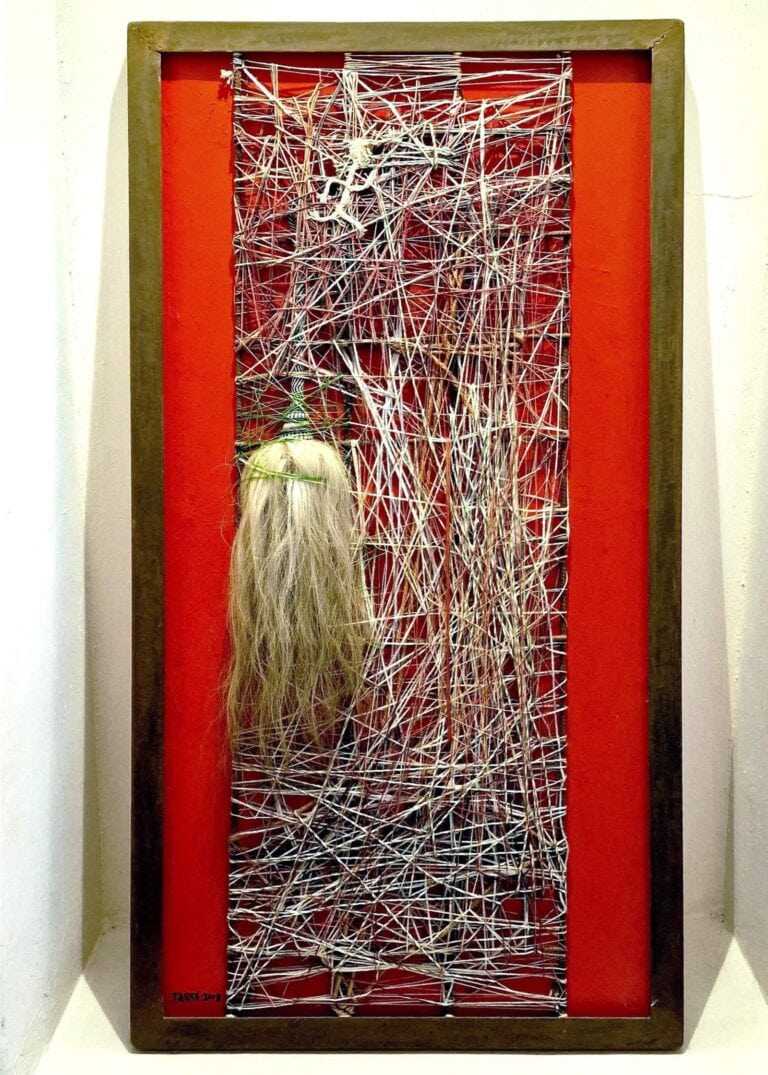

The influence of Industrial design can still be seen in Tarka’s work, which spans paintings, sculptures, mixed-media reliefs and painting installations.

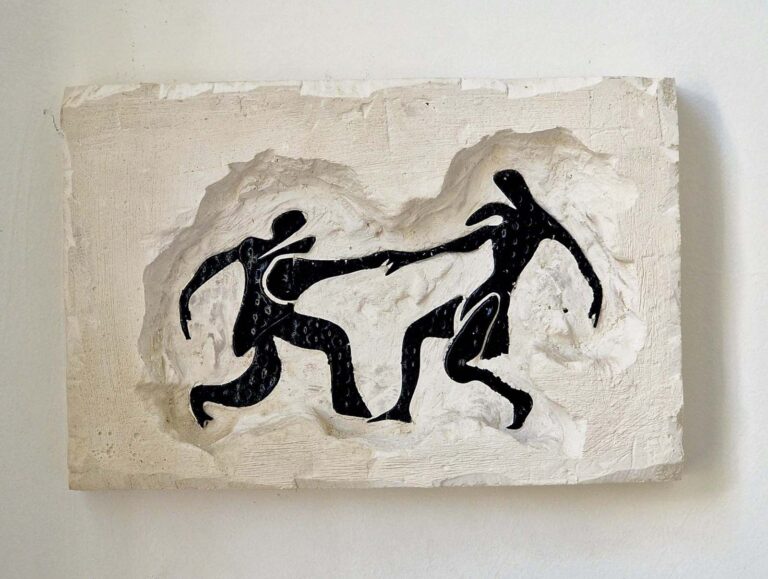

One example is in the “Exposed” series where laser-cut black figures are placed into a carved plaster wall.

“I have an obsessive need to combine perceptually irreconcilable things, such as high-tech techniques such as 3D printing and laser cutting with more traditional low-tech methods such as plaster or concrete casts and hewing,” Tarka shares.

Tarka, who is the father of three children aged 18, 16 and 10, uses primitive ethnic figures in his work but commentary is focused on Israeli society.

“Dialogue,” a series of works begun in 2015 after the Ethiopian Israeli community protested against police brutality and discrimination, explores the limitations of interpersonal human communication.

In each work of this series, two figures are shown engaged in dialogue. As Tarka explains, “The figures are ethnic but the head-on way they are communicating is very Israeli.”

The artist in these times

Tarka admits being productive since October 7 has been challenging and that it took a long time for him to go back into his Gan Yavneh studio.

“I only went back recently after a few months. No one can escape the events of that day and I found myself painting in a different color and language with lots of black and red and flags of Israel, which I have never included before.”

He is also hard at work for a group exhibition at the Ramat Gan Museum of Israeli Art beginning July 7, which will include an art performance in which Tarka will carve out a 12-meter wall.

“I am still a carver, breaking through both literally and figuratively,” he says with a smile.

For more information on Tarka’s art, click here.