When Marion Gaemers and Lynnette Griffiths turned on the black lights in their studio not long ago, they were pleased. The discarded fishing gear they were using to create their latest work of art luminesced, giving it a ghostly oceanic glow. The wearable sculpture, which has 500 silvery sardines worked into its skirt, is meant to conjure an imaginary queen who lives beneath the sea—and to warn of the dangers of ghost nets.

They call the work the Birth of the Babel Fish. It’s loosely inspired by Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, in which a fictional species of fish called the babel fish tour the cosmos, helping to translate the various languages spoken by cosmic hitchhikers so they can communicate. Gaemers and Griffiths crafted the gown as an entry to the 2023 World of Wearable Art competition to spread the word about the threat posed by rogue fishing gear, also known as ghost nets, to all the living things in the ocean.

We want to make visible the hidden pollution.

The pair of artists have been creating environmental sculptures out of lost netting and fishing gear for a decade, and together run the Ghost Net Collective in Queensland, Australia, founded in 2020. These ghost nets ensnarl and kill ocean wildlife, posing a massive threat to biodiversity and marine ecosystems. Some 1,500 Australian sea lions die every year due to entanglement in fishing nets, for example. Ghost nets also attract other debris, coiling into leviathans that become a hazard even to shipping vessels. The problem has grown over time as fishing gear is increasingly designed with synthetic materials for durability. One 2018 report estimated that ghost nets, lines, and ropes accounted for almost half of the plastic found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Some ghost nets inevitably wash up on shore, and Gaemers and Griffiths collect them during beach clean-ups. The larger ghost nets they use in their art works come to them from Tangaroa Blue, a nonprofit organization based in Western Australia that monitors the impacts of marine debris along the coastline. Griffiths and Gaemers work all the material by hand, first hosing it down to remove sand and other rubble and then sorting the pieces by color. Once the ropes are detangled, they “deconstruct” them into threads and finally “felt” them into a fabric, says Gaemers. The fabric is woven into the sculptural pieces, using twining and plaiting techniques borrowed from basketry.

It’s arduous work: Griffiths and Gaemers spent five months crafting the babel queen’s gown by hand. But they had help, too: Most of the larger installations are completed collaboratively. Gaemers and Griffiths send out kits with ghost netting and instructions for how to weave marine critters to participants all over the world. They ask that their collaborators send the pieces back to them, and incorporate them as details into their larger projects, thus spreading the ownership of the installations and helping to educate the public about ghost nets. Volunteer collaborators created all of the sardines in the babel fish skirt, they say. “Each sardine takes about 22 minutes to sew,” Griffiths told me.

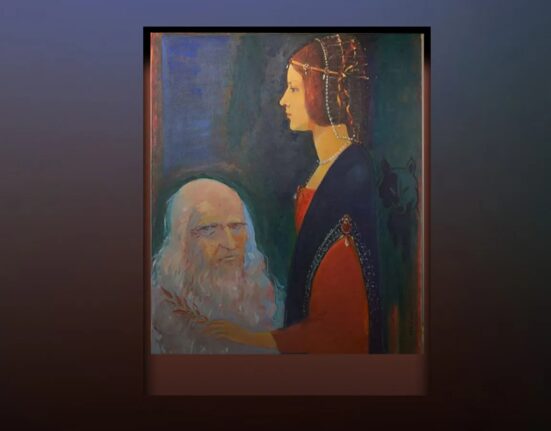

The Birth of the Babel Fish is a singular creation, weaving together the quirks of the two artists. Gaemers describes herself as “a science-fiction enthusiast,” a big-time fan of The Hitchhiker’s Guide and television series like Doctor Who, whereas Griffiths has long loved the world of fashion. The babel queen gown incorporates influences from the Elizabethan period, Griffiths says, a heyday of maritime exploration.

“We want people to be able to touch our work,” Griffiths told me. To the artists, ghost nets are a symbol for global environmental problems writ large, which generally lurk out-of-sight and out-of-mind. “The nets are silent, deadly killers, and through what we do in our work, we want to make visible the hidden pollution.” The Birth of the Babel Fish places that abstraction into a human context.

Photos courtesy of Lynnette Griffiths