There is no word for art in the Lakota language. But the power of art, in every facet of life, has drawn a boisterous group of moccasin beaders, painters, regalia artists and producers of Native hip-hop down a two-lane road that undulates through the tawny hills of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, eight miles from the nearest intersection.

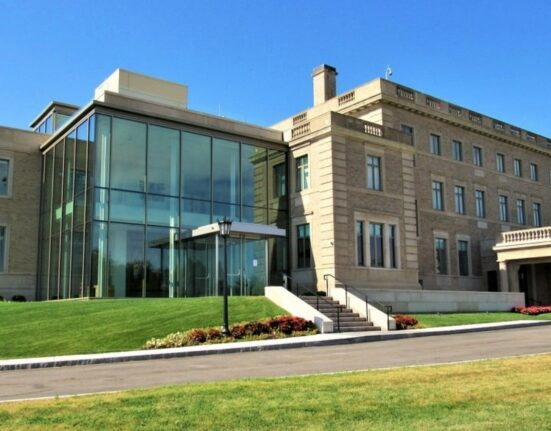

The setting is the new Oglala Lakota Artspace, a Native-run studio space that’s the first of its kind on the Pine Ridge reservation, and since its debut last May, it has liberated scores of artists from their kitchen tables. It’s a place where mothers hover over sewing machines fashioning ribbon skirts for their daughters to wear at powwows, while young hip-hop artists in requisite black T-shirts record music videos and mixtapes under the tutelage of a 30-year-old rapper and producer.

Helene Gaddie, the instructor for the Warrior Women Sewing Circle, is one of five Artspace artists-in-residence; she’s also co-founder of an organization bringing science, math and cultural education to Lakota youth. “There are a lot of statistics about our community,” she observed. “This place is a beacon of hope, a safe, welcoming space where community members excel.”

The Pine Ridge reservation, home to the Oglala Lakota Nation, spans some 3,469 square miles — a distance twice the size of Rhode Island — including a swath of canyon-colored tablelands within Badlands National Park. In recent decades, the reservation has contended with a litany of social ills tied to deep poverty, including alcoholism and substance abuse, overcrowded, dilapidated housing and youth suicide. The unemployment rate on the reservation as of 2022, according to the 2022 American Community Survey’s five-year estimates, was 10.8 percent. Its geographic isolation is compounded by spotty broadband and dirt roads that become impassable with mud in heavy rains.

The Oglala Lakota people on Pine Ridge are part of an ancient confederacy called the Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires, whose members speak three dialects of the same language with seven bands spread across reservations primarily in North and South Dakota. All Lakota tribes were once part of the Great Sioux Nation before the government divided them into separate reservations shoehorned onto greatly reduced lands.

Kyle, which many here still call by its traditional name, Medicine Root, is at the center of the reservation, not far from the site of the 1890 Massacre at Wounded Knee, when U.S. soldiers killed nearly 300 Lakota people, most unarmed and at least half of them women and children. As a tribal report notes, the collective weight of these atrocities, along with a lack of trust in mainstream society, endures today.

The Artspace is the latest manifestation of a resurgence of Native cultural traditions and ceremonies and the increased national and international visibility of Indigenous artists. The creative force behind it is Lori Lea Pourier, who grew up on Pine Ridge (one grandmother was a pioneering art teacher, and the other a quilter). She is the president of First Peoples Fund, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the cultural wealth of Indigenous artists from Alaska to Maine. When Pourier joined First Peoples in 1998, artists with ambitions were moving to the Southwest and the state arts council “didn’t come to the Rez,” she said.

Protecting the legacy is especially important, given efforts to extinguish it in boarding schools that forced assimilation and by the removal of sacred objects. “When you suppress culture, you take the spirit out of your soul,” Pourier added. “Through art, we’re bringing that spiritual and cultural knowledge back to the community.”

A striking artwork itself, the Artspace was designed by Tammy Eagle Bull, who grew up on Pine Ridge and is considered the first licensed Native woman architect in the United States. The Lakota worldview imbues every inch, starting with the East-facing courtyard echoing the entrances to tipis, their traditional name for dwellings. The circular layout evokes the sacred hoop of the stars, or Lakota Star Knowledge, the belief that the stars are mirrored on Earth and align with seven sacred sites in the Black Hills.

Eagle Bull, a professor in the Indigenous Design Collaborative at the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at Arizona State University, is one of a growing roster of Native architects helping tribes “reshape their built environment to accurately reflect their culture and values,” she said.

The opportunity to revive a cultural practice inspired Shyla White Lance to make the 170-mile round trip from Rapid City to the Artspace, where she took a beading class, threading riotously colored glass specks onto needles to make moccasins. “I didn’t have anyone to teach me or learn from,” she said. “It’s comforting to have this time to just sit and bead.”

The focus here is on teaching and expanding ceremonial and artistic traditions, with a subtle dose of social service. A recent Saturday found Leslie Mesteth, the Artspace program manager, chopping carrots and onions for a lunchtime soup. First Peoples Fund provides meals and prepaid gas cards for artists and community members, a nod to everyday realities: In Oglala Lakota County, where the Artspace is located, the median household income was $32,279 and over half of the residents lived in poverty, according to 2022 American Community Survey estimates.

The artists in residence here are a Renaissance bunch: Cat Clifford is a former rodeo bronc rider who hand-tools rodeo chaps and other leather pieces and does stunt work for Hollywood. He is also a singer and composer who appeared in “Nomadland,” strumming his guitar in a pickup while his song “Drifting Away I Go” accompanies footage of Frances McDormand walking through the Badlands. His studio has the luscious smell of oiled leather.

The Artspace, built for $3 million from mostly philanthropic grants, evolved from a survey commissioned a decade ago that included extensive conversations with artists. It found that more than half of Pine Ridge households ran home-based small businesses — the vast majority related to the arts. But artists were struggling financially and the growth of a local arts economy was stymied by a lack of access to credit, capital and supplies. With the reservation’s acute housing shortage, artists desperately needed space for creating work.

Help came first in the form of a bus, the Rolling Rez, a mobile arts studio, bank and credit union. (It is currently waylaid with mechanical woes.) Today, the Lakota Fund, which provides microloans and other services for artists, is based at the Artspace and offers workshops and coaching sessions on how to run a business.

Many artists at the Artspace and on the Pine Ridge reservation sell their work at the annual Northern Plains Indian Art Market in Sioux Falls and similar shows. Nearly all rely on Instagram, which has flipped the script on the old-school trading post by letting artists control prices, relationships with customers and how their work is presented.

The Native artist Dyani White Hawk, recently named a MacArthur Fellow, received an Artists in Business Leadership fellowship from the First Peoples Fund and has mentored others at the Artspace. “These grants can be pivotal to an artist’s career,” she said. “Most people who are curators or reviewing grant applications are not Native,” she added, and can’t always evaluate a Native artist as well as an organization like First Peoples can.

“A lot can be missed without that library of knowledge,” said White Hawk, who is convinced that other tribes, including her own Rosebud Sioux, will eventually replicate the idea of an Artspace where talent can flourish.

That includes Marty Two Bulls Jr., one of the first Artist Laureates of the Oglala Lakota nation. He led a team of artists in creating the visual touchstone of Artspace: a stainless-steel outdoor sculpture in the shape of two inverted triangles representing Star Knowledge. The facets of the triangles are engraved with constellations and corresponding sacred sites.

“Our nomadic ancestors used the stars the way I use my phone, following the buffalo herds and using stars to navigate the Plains,” he said at his home in Rapid City. Recently he created an immersive installation at the Academy Art Museum in Easton, Md., a critique of consumerism and squandered resources, told through the metaphor of the bison, whose extinction by settlers devastated the livelihood and culture of the Lakota peoples.

Artmaking here is highly collaborative: The outdoor sculpture was planned by the four artists during the pandemic, in Zoom meetings, in consultation with Richard Two Dogs, a medicine man and traditional healer whose teachings on Star Knowledge — lost to Lakota culture years ago — had been preserved by his family.

Two Dogs, who regularly works with suicidal youth, says that red paint applied to a young person’s forehead by elders in a ceremony can be an effective form of spiritual intervention and healing. “Art has helped us as far back as we can remember,” he said. “It plays a large role in how we painted our tipis, our horses, ourselves and in our way of praying. We believe you are recognized by the spirits by the paint you use.”

That healing spirit runs deep in the Black Hills, where the Lakota people are said to have emerged and where important ceremonies and traditional stories take place.

On a chilly mid-October day, Pourier, the First Peoples Fund president, and her colleague Lynette Two Bulls, a cultural leader from Montana, drove through sleet and snow in the Black Hills to ground a reporter in Lakota values. On the way to Black Elk Peak, a sacred site, we passed Mount Rushmore, regarded by many tribal people as a desecration of the most sacred lands. As we neared the Peak, a barricade blocked the main road. “We should have driven through it,” Pourier said wryly. “It’s our damn land!”

At Mato Paha, or Bear Butte, the grasses took on autumnal colors and fog hugged the summit. Tree branches were swaddled with prayer offerings: bright cloth bundles as far as the eye could see, filled with traditional tobacco. Many had been placed there before Sun Dance ceremonies, a summertime practice involving days of fasting that was banned by the federal government and went underground until passage of the 1978 Indian Religious Freedom Act. Two Bulls lit a prayer offering, the fragrant smoke curling with the wind. It didn’t take long to absorb a key teaching: Art and beauty are all around us.

Nurturing Talent in Kyle

Keith BraveHeart was one of many artists whose insights informed the Artspace. During his childhood in Kyle, he sketched the landscape and the people around him and showed a natural talent for art so promising that a teacher raised gas money to help him attend the Oscar Howe Summer Art Institute 300 miles away at the University of South Dakota. It is named for the artist (1915-1983) who broke the clichés of Indian art with an abstract style called “Dakota Modern.”

Today BraveHeart, a tribal Arts Laureate, is on the faculty of Oglala Lakota College and is a working artist. Storytelling imbues his painting of a 1950s blonde vacuuming a buffalo hide, oblivious to the searing history of skinned buffalo outside her window. Others, of Lakota leaders, often bear the graphic icons for Bluetooth and Wifi.

A descendant of a female Wounded Knee survivor, BraveHeart created a large-scale painting, titled “Wowicala Iciwayankapi” (“Differences in Worldviews”), an arch look at selfie-taking tourism at the revered massacre site.

Another artist whose insights informed the space was Dwayne Wilcox, whose often-whimsical ledger drawings of modern life on and off the reservation, from dialysis hookups to Greyhound buses, now reside in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale.

“I think of it as a camera for Native people before the camera,” he said of ledger art, the 19th-century pictograph chronicles by tribal artists made by recycling settlers’ ledger pages. Once a recording of hunting, battles and other rituals, the Plains art form has been revived as an expression of contemporary life and resilience.

Where Art Is Solace

The landscape in and around Kyle is imbued with deeply unsettling memories for those who recall firsthand the suffering that took place there. Richard Red Owl, an 83-year-old self-taught Lakota artist, lives on Bombing Range Road, named for the huge swath of Pine Ridge seized by the Army as a practice range during World War II. He grew up poor, but learned to hunt deer, chop wood and dry meat.

His parents, migrant farmworkers in Nebraska, sent him to the Holy Rosary Mission boarding school in Pine Ridge. “It was wicked,” he recalled. Even the youngest children had to mop the floors, “and if you didn’t you were spanked with a leather strap. At school they never let you talk Indian.”

A respected elder, Red Owl now counsels young talent at the Artspace but works from his home studio, where an eagle feather and a gourd rattle dangle from his paint-splattered easel. “Indian art wasn’t always ‘art,’” he pointed out. “Everything had a use.”

Several of his works address Wounded Knee, with concho belt ornaments and elk teeth representing items culled by U.S. soldiers from the dead. “It was something terrible: the soldiers stripping the bodies and taking what they could,” he said.

The site is held close by many people here, much like the Sept. 11 site in Lower Manhattan, said Craig Howe, founder and director of the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies (CAIRNS), which organized a 2018 exhibition on Wounded Knee. Roughly 80 percent of Native people on Pine Ridge have a connection to the massacre, passed down through family narratives, Dr. Howe said.

“When we pray in ceremonies we call on the people buried there to come and help us,” said Mesteth, the Artspace’s program manager, who is sixth-generation Lakota. “We still hold them in our hearts.”

While art can hardly be expected to assuage the legacy of violence and its aftermath, it is having a positive impact, especially on young people, said Tatewin Means, the executive director of the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation, which offers programs focused on youth leadership, food sovereignty and homeownership. “It’s reframing and shifting the narrative, so that we become the storytellers of our own community,” she said.

It can also provide solace at difficult personal moments. Talon Bazille Ducheneaux, 30, who runs the Wicahpi Olowan Music Program in a wing of the Artspace, says it was music by Maniac the Siouxpernatural and other Native hip-hop artists that helped carry him through a series of family crises involving opioid addiction, divorce and neglect, and parenting his little brother while he himself was still a child. He did well enough in school to attend the University of Pennsylvania but said “survivors’ guilt ate me up inside.” Later he lost his beloved little brother to a gun accident.

Now a First Peoples staffer, Ducheneaux produces albums, music videos and mixtapes and recently shepherded the talents of Santee Witt, a 50-year-old ceremonial musician who hankered to branch out. He just released his first album of folk and R&B.

Though the Artspace is still young, the garage stage adjoining the studio has taken on a life of its own. Audiences flock to hear young musicians jamming near a mural of a Plains woman encircled by dragonflies that was painted by Lakota youth. The Warrior Women are sewing fabric with Lakota Star Knowledge motifs to jazz up the studio’s acoustic panels. As Ducheneux, the Artspace’s young impresario, observed: “We have all this art bursting at the seams here needing a place to get out.”