Gov’t advised to solve administrative problems stemming from language barrier, bureaucratic red tape

Editor’s note

This article is a part of The Korea Times’ 2024 series focusing on “Diversity, Inclusiveness and Equality.” — ED.

By Pyo Kyung-min

Artists from all over the world come to Korea, which has evolved into a cultural powerhouse, with dreams and aspirations. But their dreams are frequently shattered due to harsh realities characterized by workplace accidents, insufficient legal protection, and cultural barriers.

Lily, a woman from Southeast Asia, who chose not to share her full name and instead used a pseudonym, came to Korea eight years ago with high expectations and a passion for “hallyu,” also known as the Korean Wave.

When she saw a recruitment notice last September for foreign artists to participate in a dance piece supervised by a Korean performance company, Lily happily applied and was delighted to be selected for the performance.

However, her optimistic spirit was crushed when she slipped and fell on the stage floor twice during rehearsals, leading to a severe knee injury. The company organizing the project denied any liability, asserting that her injuries occurred during rehearsals, while she had not yet performed on the actual stage.

Help did not come from from public agencies, but from Park Kyong-ju, the leader of the multicultural troupe Salad. Park reached out to Arts Council Korea’s Performing Arts Department to investigate the details of Lily’s case and managed to raise a significant portion of the funds required for her treatment.

Despite the support, Lily was left with the huge burden of medical expenses and a lengthy recovery period.

“I remember the doctor saying it could take more than two years to fully heal and go back to my performing career,” she told The Korea Times during an interview last December.

Due to her injury, Lily, who majored in creative arts, was unable to participate in her graduation recital, resulting in a setback to her academic timeline. This unforeseen circumstance has jeopardized all her post-graduation goals and plans.

“I haven’t even told my family about this, because they will worry too much. I also didn’t tell my friends in Korea much about what was going on because I know they’re all busy. I’d hate to cast more burden on them.”

Plight of E-6 migrant artists

Lily’s case reflects a broader challenge faced by foreign artists in Korea, who often lack guaranteed rights within the industry.

The struggles faced by holders of the E-6 (culture and entertainment) visa in Korea, specifically designed for foreign nationals in the arts, entertainment, performance, broadcasting, and related fields, go beyond just workplace injuries.

A total of 3,883 foreign artists held E-6 visas as of January 2023, according to government data. However, a considerable number of immigrants utilizing other visas, like the E-7 (foreign national of special ability) visa, F-2 (resident) visa and the newly introduced K-culture training visa, also known as the hallyu visa, are also believed to be involved in artistic pursuits.

A male Ukrainian artist involved in cultural performances on Jeju Island faced a similar ordeal in 2022. The artist suffered injuries in April, but the business owner declined to provide compensation, arguing that his case did not comply with the requirements of industrial accident compensation insurance. The owner then reported the artist to the Korea Immigration Service, citing that he had left the workplace for treatment without permission.

According to a 2014 survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea on E-6 visa holders, 68 percent of female respondents, or 82 out of 120, said they experienced sexual violence, including rape or unwanted physical contact. For both male and female respondents, more than half, or 83 out of 151, were victims of sexual violence.

Verbal violence affected 53 percent, while physical violence impacted 46.4 percent of respondents. Additionally, 46 percent and 49.1 percent experienced their employers seizing passports and foreign registration cards, respectively.

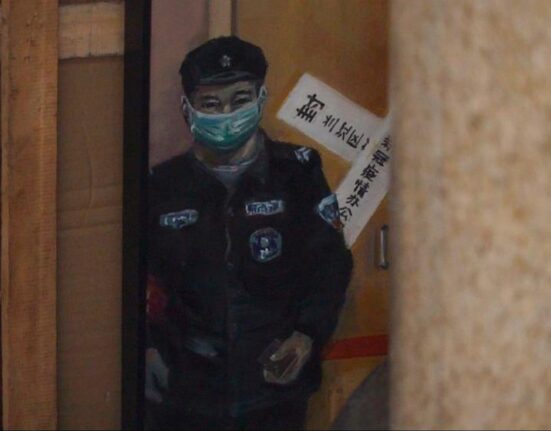

Barri Tsavaris, front row right, speaks at a press conference urging the Korean government to create a safer and fairer work environment for all artists, regardless of nationality, in this May 24, 2022 photo. Korea Times photo by Jon Dunbar

Legal, administrative hurdles

Despite the influx of artists from abroad drawn by hallyu’s global appeal, legal protection for them remains ambiguous.

Bae Seong-hee, a member of the National Assembly Research Service, highlighted in a report titled “The Status and Future Agenda of Foreign Artists in Korea” released in December 2022, “The surge in global interest in hallyu content, exemplified by BTS, the movie ‘Parasite’ and the Netflix series ‘Squid Game,’ has led to an increased influx of foreign artists seeking opportunities in Korea.”

In an interview with The Korea Times, Bae pointed out that foreigners aspiring to pursue art in Korea face a concerning lack of protection due to the “arbitrary interpretation of the law resulting from the bureaucratic red tape of subordinate institutions.”

Laws in Korea that safeguard the status of artists, such as the Act on the Guaranteed Status and Rights of Artists and the Artist Welfare Act, provide comprehensive definitions of artists without making any reference to nationality. And this has led to erroneous perceptions that the laws protect only Korean artists. Both define an artist as “a person who earns a living by engaging in artistic activities, contributing to enriching Korean culture, society, economy and politics, who can verify his or her activities of creation, in-person performance, technical assistance, etc.”

Bae criticized the ambiguous definition and said, “Anyone contributing to improving the quality of life of Koreans should be recognized as an artist.”

However, the Korean Artists’ Welfare Foundation interprets the law as applying only to Korean nationals. Foreign artists in Korea face barriers in obtaining the foundation’s Artistic Activities Certification, which is needed to access administrative support.

Bae’s report revealed that the foundation issued certificates to just 209 foreign artists between 2014 and 2022. Exceptions are made for foreigners falling under specific categories, such as those married to Korean nationals, caring for Korean family members, recognized refugees, ethnic Koreans with foreign nationalities who possess permanent resident status and non-Koreans who obtained permanent resident status under the Immigration Management Act.

“Administrative officials may find the multilingual workload burdensome and there are concerns about foreigners returning to their home countries after receiving government support. The exclusion of foreign artists from applications appears to stem from expediency and a lack of manpower,” Bae said.

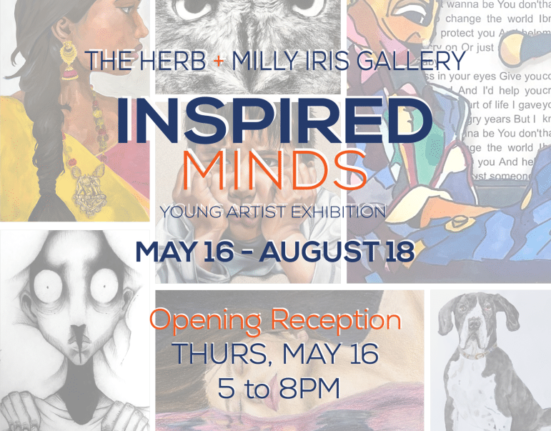

The Korean Artists’ Welfare Foundation’s guide to applying for Artistic Activities Certification, available only in Korean / Screenshot from Korean Artists’ Welfare Foundation’s website

Voice of advocacy

Critics argue that the administrative red tape reflects a broader discriminatory perception of foreign nationals in Korea. Others suggest that the existing laws, formulated at a time when there were few foreign artists in Korea, should be revisited and revised to better accommodate the current reality.

Park at Salad, who also advocates foreign artists’ rights, called for a more inclusive approach, pointing out a systemic bias in Korea against migrants.

“We do already have a pretty well-established system. But foreigners don’t just stay in Korea; they too pay local taxes, income taxes and other levies. It’s hard to understand why it’s so challenging for foreigners to access the rights they are entitled to,” Park told The Korea Times.

“At a fundamental level, migrants need to be aware of the rights available to them. Unfortunately, resources like websites and YouTube education videos lack translated versions. The notion that individuals can’t access information simply because they are from another country is undoubtedly a form of discrimination.”

Lee Jin-hye, a lawyer with Migrants Center Friends, emphasized the widespread problem of insufficient information impacting migrant workers, including artists. She pointed out that this issue is a direct consequence of systematic discrimination.

For instance, Lily only discovered the importance of scrutinizing her contract and understanding the applicability of industrial accident insurance after her injury.

Lee proposed a step-by-step approach to address the issue at the grassroots level.

“To prevent migrant workers from failing to apply for industrial accident claims due to a lack of information, there should be active education on hospital procedures and industrial accident insurance upon arrival. Immediate report to the government should occur in case of injuries, with multilingual support services specializing in industrial accidents, including offering telephone consultations and visiting hospitals together with the victim,” Lee suggested through a written interview.

Ryu Ji-woong, a law professor at Dongkuk University, cited bureaucratic and language barriers faced by migrant artists.

“In terms of legal systems and policies for foreign artists, Korea has the Master Plan for Immigration Policy and is considered to have a legal system for foreigners that is similar to or comparable to that of Korean nationals,” Ryu said.

“However, the reality is that migrant artists are not covered by the Act on the Guaranteed Status and Rights of Artists, and their language barrier and administrative problems are not properly addressed. Related government agencies such as the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Health and Welfare do not have an established work protocol for issues involving foreign artists.”

He suggested that the government should include foreigners in the legislation for artists’ rights and make sure there are no gray areas.

“The government should conduct a comprehensive, face-to-face survey to understand the type of work they are engaged in and their quality of life. It’s essential to focus on gaining insights into the specific experiences of artists residing here, rather than merely compiling a list of names or documents,” the professor said.

“On a personal level, individual migrant artists need to actively learn about their status and the administrative system in Korea and utilize migrant communities to voice their opinions on the unfair treatment and discrimination they experience in Korea.”

Despite all she has gone through, Lily still maintains a positive impression of Korea and considers herself to be lucky.

“Surprisingly, my time in Korea has been positive overall. I believe I’ve been fortunate with the support I received. While I haven’t faced severe exploitation like some other immigrants, it’s disheartening to realize the measures I should have taken only after the incident,” she said.

“I just wish none of my friends will have to endure what I went through, but I understand it won’t be easy here.”