IN 1943, when Bengal experienced one of the most devastating famines of the 20th century, witnessing close to 30 lakh deaths, several artists of the time channeled their agony into their work, considering it their responsibility to paint the harsh realities. Among them was a young Gobardhan Ash. Already an artist of repute who had won several awards — including the first prize from the Madras Fine Arts Society and silver medal from the Delhi Fine Arts Society in 1936 — his earnest portrayals detailed the melancholic times and the sufferings of the starving millions.

Referring to some of these works that now form part of a book accompanying the exhibition titled “The Prinseps Exhibition: Gobardhan Ash Retrospective”, Brijeshwari Kumari Gohil, vice-president of Prinseps auction house, notes that Ash had been a proponent of social realism for years before. A display wall at the Kolkata Center for Art and Creativity is testament to it.

If a 1937 pen on paper has a man resting under the shade of a tree, in the 1939 charcoal Fakir he sketches the helplessness of a man he saw begging in Kolkata’s Park Circus. “A pioneer of social realism, for him, Indianness was not associated with any technique or style. It was about depicting the stark realities of the time. He was constantly sketching what he was seeing in the purest and starkest forms. This was not the oriental India that had been popularised but the real India,” says Gohil, who has curated the exhibition with Harsharan Bakshi.

Featuring over 100 works spanning 1929 to 1969, the thematic showcase makes an effort to represent the various phases of the rather forgotten Begampur-born artist’s oeuvre, also bringing his voice through words from his diaries.

Demonstrating a keen interest in art since childhood, as a student, Ash’s academic books were often filled with drawings. At 17, the desire to find a suitable art training institute took him to Banaras, without the consent of his guardian, but the journey proved futile. In 1926, Ash joined the Government School of Arts, Calcutta. It was here that he found a mentor in Atul Bose, who not just honed his skills but also became a lifelong guide. The exhibition also includes Ash’s 1926 dry brush horse, Breathing Time, that caught the attention of Jamini Roy at the annual exhibition of the institute. When changes in the education system led to strikes and frequent disruptions, a disillusioned Ash decided to join the Government School of Arts and Craft, Madras in 1931-32 but his stint there too was short-lived.

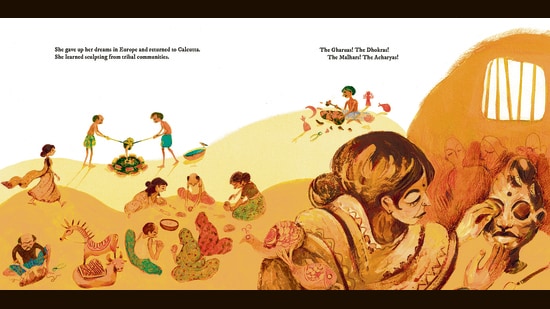

The quest for modernism, meanwhile, brought him together with other artists pursuing the same dream. Both the 1931 Young Artists’ Union and the Art Rebel Centre in 1933 — that he played central roles in – were aimed at discovering artistic forms distinct from the prevalent neo-Indian style and British academism. Discussing Ash’s own works from the period, Gohil notes how he would discover beauty in nature and also often wander streets to find subjects and portraits. If a 1939 watercolour of the Kolkata Moulali Church is symbolic of his relationship with the city that was his home from 1926 to 1947, the 1940 oil works People of Rajasthan and Ploughing depict his love for nature and his travels.

One of his most celebrated set of works that came in the later ’40s also, incidentally, formed part of a joint exhibition of the Calcutta Group and the Progressive Artists’ Group in 1950. Moving away from naturalistic forms, the “Avatar” series was influenced by diverse inspirations — from folk aesthetic to a distinctly different colour palette — to inform portrayals that captured the essence of the subjects. Devi Bahen (1948), for instance, originated from his trip with Bose to Mahishadal Rajbari (a royal palace in West Bengal), where he drew animals he spotted there. The gouche Mother and Son captures the endearing bond in thick strokes and vibrant colours. “He was constantly exploring and experimenting. He would be fixated on a certain subject for years and then do something else… There was a constant turmoil, sense of doing more and not conform,” states Gohil.

So, a decade later came another series, dedicated to children and their myriad moods that Ash observed for over a decade. The studies, in his own words, culminated with Commander-in-Chief (1957-67), with three children wearing disparate expressions ostensibly at play.

Though his studio had always been open for students and fellow artists, Ash spent his later years distanced from urban chaos. In 1956, he established the Fine Art Mission Free Art School in Begampur for boys in the village to study art. “Gobardhan, being a keen observer, would take his students outdoors to fields, stables, or cowsheds to study buffaloes. Ash also wanted to demonstrate life studies to his students,” notes the publication.

Working till the end, his very last self-portrait was completed a day before his demise in December 1996. Covering the period of the showcase, the exhibition features self-portraits from 1936 to 1957, in varied mediums, from cross-hatchings to oil. Appearing as dialogues with the self, the practice was a ritual that was also perhaps a way of documenting perceptions of the self.

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 14-04-2024 at 07:12 IST