G

uillaume Lethière is the big summer exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown in northwestern Massachusetts. Rural, pretty Williamstown is a culture hub on the Vermont border at the end of the Berkshires mountain range. Though the farthest flung draw for the New York summer people, the Clark’s summer extravaganza unofficially inaugurates the Berkshires’ season for art tourism.

Lethière (1760–1832) was, until the Clark and the Louvre joined in this show to survey his career, an unremembered history painter and portraitist working during the French Revolution and the Bonaparte era from the wee pharaoh’s rise to his Waterloo sunset. It’s here-and-there awkward but enriching. With Bastille Day nigh, it was a treat.

Let’s put what’s awkward on the table. More and more, the Clark is breathless and frenzied in marking its territory in the field of oppression art history. Lethière, you see, was born in Guadeloupe, “the son of a white plantation owner and an enslaved woman of mixed race,” we’re immediately told. “Look at me,” the very white, very flush Clark wants the Prog world to know, “we can play in the Oppression Olympics, too.” Its marketing and the show’s catalogue foreground race, not art.

As themes go, Lethière’s bloodlines pique but don’t engage, much less excite. We learn later that Mama Lethière was in fact a free woman, herself mixed-race, and she might never have been a slave. He’s no James Baldwin, and his life doesn’t cue “We Shall Overcome.” His rich father, with whom he had an affectionate relationship, launched him as an artist in Paris and made him his heir. Race doesn’t figure in his subsequent career as director of the Académie de France in Rome or as the chief painter in the court of Lucien Bonaparte, Napoléon’s brother. Among high-establishment artists in Paris, he was respected and valued as a peer. He was a contemporary of Jacques-Louis David’s and a competitor, too.

The exhibition is handsomely presented, as are all Clark exhibitions. By his mid 20s, Lethière was winning prestigious prizes taking him to Rome to study at the Académie de France. The Death of Camilla, painted in 1785 and one of his competition paintings as he sought to go to Rome, shows that he does gruesome well. As Livy reported it, Camilla, from the rich, political, and martial Horatii clan, was in love with one of the three brothers from the Curiatii clan, archenemy of the Horatii. Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii, the supreme flower of French neoclassicism, depicts the brothers pledging to fight to a convoluted death.

One of Camilla’s brothers, learning about her love interest, murders her. She placed love above tribal loyalty. Camilla, painted by Lethière, looks fussed and mussed and very dead indeed, though one exposed and ample breast suggests she was a sexpot to the end. Near Camilla is her servant, so devastated that she shrouds herself. It’s a nice touch of Grand Guignol. Next to Camilla — the painting — is a nude torso beefcake painting that Lethière also did in 1785. Lethière’s not what I’d call a carnal painter, but he has a knack for ruckus, real or implied. His beefcake looks like a hothead, Stanley Kowalski–style. Kowalski, though Polish-American, hails from New Orleans, our Creole capital. There must be something in the water.

David’s Oath of the Horatii, painted at the same time, is as spartan as Lethière’s picture is hammy. Lethière is no David. That’s not a crime, and the exhibition never suggests its subject is a supernova.

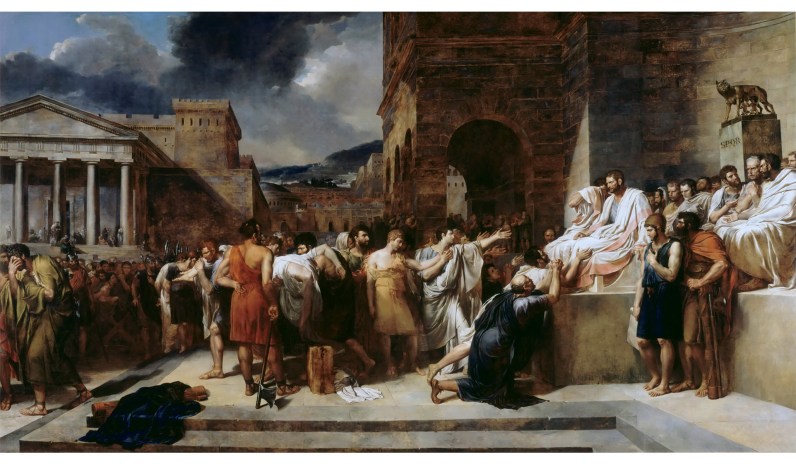

Lethière was in Rome from 1786 to 1791, before the Reign of Terror. Heads in Paris weren’t yet rolling like bowling bowls on a Saturday night, but Rome was a nice place to be — as always — and Lethière built lifelong friendships and connections. He also conceived what would be his favorite subjects, seen in Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death and The Death of Virginia. For me, these were the high points of the exhibition, and they show Lethière at his best but also at his most formulaic. In the galleries, we first see his versions of Brutus from the late 1780s.

This Brutus isn’t the one of whom Julius Caesar remarked “with friends like these” but a far earlier Brutus who, circa 509 b.c., overthrew the last king of Rome in favor of the Roman Republic. When his own sons tried to oust the republic, an act of treason, Brutus had no choice except to order their execution. In Lethière’s take, one son has already gotten whacked, the executioner holding his head high, while another quakes, knowing he’s next. Brutus, showing no emotion, witnesses from his ruling perch. Rows of men beg him to be lenient. Women faint.

The theme is the primacy of principle — the integrity of the nation — above money, convenience, prestige, friends, and family. Lethière might have been in Rome enjoying his pasta carbonara, but he knew what was cooking in revolutionary Paris, and, we’re told, he sympathized.

Brutus is packed with people and architecture. Lethière knows how to organize complexity. Many of his high-drama pictures have rows of beseechers, arms raised. The look is never dull. The Clark presents Lethière’s drawings, at least one painting, and an engraved version, so we can see how he developed the story. In 1811, Lethière painted a 25-foot-wide version of his Brutus. It’s at the Louvre, too big to fit in the Clark’s galleries. I’m sure it’ll be in Guillaume Lethière when it goes to Paris.

The Clark owns the Brutus painting on view in Williamstown. It’s 23 by 39 inches, so it’s not small. The surface sparkles with life — and ugly death — as well as energy.

Death of Virginia is another Lethière opus and was meant to be one of a quartet of big, glam history scenes along with Brutus and Death of Caesar, which didn’t get beyond a very finished oil sketch, likely by Lethière, and an idea for a scene of the Emperor Constantine defeating Maxentius at Milvian Bridge in a.d. 312. Virginia is another figure, possibly from legend, given to us by Livy. About to be enslaved during another Roman Republic tempest and made a concubine, her father stabbed her to death in a costly triumph of virtue over vice.

Does Lethière’s fascination with Brutus and Virginia suggest he had father issues? Maybe, the exhibition suggests, but maybe not. It’s probably wishful thinking. By the 1790s, Lethière and his father weren’t exactly tight — his père lived thousands of miles away — but their relationship seemed happily settled. Lethière, in fact, inherited the sugar plantation in Guadeloupe on his father’s death in 1800. The Jacobins abolished colonial slavery in 1794, but Napoléon reinstated it in 1802. Lethière owned the property until 1809. Did whoever managed the place on his behalf use slave labor? We don’t know. Does Virginia’s story resonate because of her brush with enslavement? Possibly, we’re told, but I doubt it. Her story doesn’t much align with Lethière’s.

The exibition suggests that Lethière is a victim of what it calls “the industry of slavery,” but he wasn’t. Louis-Léopold Boilly’s iconic jewel-box Meeting of Artists in Isabey’s Studio, from 1798, is in the exhibition. It depicts 30 or so Paris artists, critics, actors, and architects influential during France’s First Republic, which was overthrown by Napoléon. Lethière is in the middle. He tends to land on his feet. In 1807, he was appointed director of the Académie de France, taking him back to Rome in one of the French art world’s most prestigious jobs. France had a handful of racial exclusion laws, but they were rarely enforced.

Plunk in the middle of Guillaume Lethière is a large gallery entitled Caribbean Circles. It treats the substantial community of artists and intellectuals in Paris, during Lethière’s time there, who had roots in France’s Caribbean colonies. Empress Joséphine — there’s a heavy hitter — was from Martinique, though, aside from her portrait by Andrea Appiani, from 1796, we never learn anything about her ties to fellow Creoles.

The show has a drawing of Jean-Baptiste Belley, after Girodet’s famous portrait. Belley, a freed slave living in Haiti, was the first black deputy elected to the National Convention, France’s revolutionary government. Girodet’s striking portrait of Benjamin Rolland, a freed slave turned artist and an acolyte of David’s, is there. Théodore Chassériau, an Orientalist painter whose work I like a lot, was born in Santo Domingo to mixed-race parents and moved to Paris as a baby. His self-portrait is also in the show.

There are four portraits of Alexandre Dumas, he of The Three Musketeers, whose father was a French general, born in Santo Domingo to a rich white father and a black slave mother. Dumas père and Lethière were close friends. We also see a handful of mediocre landscapes from around 1800 by Jenny Prinssay, a rich Creole woman artist who worked in Paris and who might have known Lethière.

The View<\/I>”}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/keith-ellison-blames-car-manufactures-for-uptick-in-theft\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/6601d78e607b761e33010160\/Ellisonwide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Keith Ellison Blames Car Manufactures for Uptick in Theft”}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/toronto-police-tell-residents-to-leave-key-fobs-at-their-door-to-avoid-fatal-break-ins\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/65f9a5b5efb6c028c90fcbf5\/Torontowide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Toronto Police Tell Residents to Leave Key Fobs at Their Door to Avoid Fatal Break-Ins”}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/rep-swalwell-claims-he-doesnt-like-bans\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/65f36180d67c8275680c3396\/Swalwellwide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Rep. Swalwell Claims He Doesn’t Like \u2018Bans\u2019″}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/rep-jayapal-tries-to-claim-robert-hur-exonerated-biden\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/65f1f2a132a73229c202a1b5\/Hurwide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Rep. Jayapal Tries to Claim Robert Hur \u2018Exonerated\u2019 Biden”}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/biden-says-he-shouldnt-have-said-illegal\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/65f0983855c6888e14087d89\/Illegalwide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Biden Says He Shouldn’t Have Said \u2018Illegal\u2019″}},{“clickthrough”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/videos\/biden-uses-the-state-of-the-union-to-lie-about-alabama-and-ivf\/”,”poster”:”https:\/\/www.nationalreview.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2019\/07\/pride-parade-nyc.jpg”,”type”:”video”,”url”:”https:\/\/play.aniview.com\/60d5e58543972f2377389576\/65eb9271f2bad2880a02af04\/Ivfwide.mp4″,”entry”:{“name”:”Biden Uses the State of the Union to Lie About Alabama and IVF”}}]” data-variant=”instreamFloating”>

The gallery’s messy since there are so many story lines. Some are irrelevant. Lethière didn’t know Chassériau. The art’s in the show merely to illustrate that there was a critical mass of Caribbean figures in Paris, aside from Lethière. It seems superficial. Just dropping names and faces doesn’t fashion a niche culture that intrigues. With a deeper dive and some Promethean storytelling, it might have been fascinating. Like most curators, the Clark’s are too timid.

So many of Dumas’s characters in The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo drew from his father’s epic life. Why not enliven all those stiff portraits of Dumas? The curators give us nothing about Creole business titans in Paris. We don’t learn much about the Creole aristocracy in the Caribbean, which was inbred, royalist, jealous of its privileges, and hayseed-rural. What’s clear — and surprising — is how often mixed-race Frenchmen with Caribbean roots did well in Paris. The French, notorious racists, evidently do experience bouts of enlightenment.

Lethière never lost interest in things Caribbean. His home and studio when he lived in Paris were Creole magnets. Like many well-off Parisian leftists, he was very much invested in the Haitian Revolution, which lasted from the early 1790s until 1804 and was viewed as a slave rebellion on the order of the one led by Spartacus nearly 2,000 years earlier. A video-screen copy of Oath of the Ancestors, painted by Lethière in 1822, is in the exhibition. It’s 11 by 7 feet and, indeed, a clunker. Lethière gave the painting to the new Haitian nation, and it still lives in Port-au-Prince.

Back in Paris by 1816, Lethière had a good, productive end-of-career phase that’s the subject of the last gallery. Did he veer toward the subjective, the irrational, the transcendent, or the emotive — all characteristics of Romantic-era art? Yes and no. His troubadour paintings evoke the spirit of Walter Scott. His final stabs at The Death of Virginia are stormy. The story, extreme as it is, fits the Romantic zeitgeist.

I love what seems to be his last project. A very finished oil sketch from 1830 or 1831 depicts the Marquis de Lafayette introducing Louis-Philippe as the new king, the Citizen King, after a popular revolt ousted Charles X, who was a proponent of the divine right of kings to rule without checks and balances. Lethière was commissioned by Louis-Philippe to paint a large, ceremony-worthy version, but he died before he tackled it.

His oil sketch crackles. It’s well-organized — Lethière is good with crowd control — but crackles. It’s got a newsy feel. Lethière’s old convention — outstretched arms — isn’t for begging. They’re not salutes but gestures saying “I want to touch.” Louis-Philippe was, after all, the closest France had come to a king who was of and for the people. Lethière, once more, had picked the winning side.

The catalogue, at 400 pages, is a doorstop, but the essays, many by French scholars, are good. It’s heavy on history, so I now know lots more about slavery and revolution in the French Caribbean. We never learn, in the show at the Clark or in the book, much about where Lethière fits in the rich, complex art history of his time, alas.

One of the many things I like about Guillaume Lethière is the attention it attracts to Old Master history paintings, which usually enacted issues of their day. Visually, they strike many of us as pretentious, even bilious, or fussy. But over-the-top isn’t a bad thing in itself, and Lethière does it well when the scale’s right. I’m happy to see the Clark and the Louvre bring his career back to life.

So, a joyous Bastille Day! After Sunday’s election in France, I hear there’s a run on guillotines.