David Adickes is most famous for his large sculptures, including his collection of presidential busts, the 67-foot-tall Sam Houston statue in Huntsville, and the 21-ton Virtuoso sculpture in downtown Houston.

Mae West said, ‘You only live once. But if you do it right, once is enough,’” muses David Adickes, 97, at the base of the stairs of his Nance Street workshop. Coming from a near-centenarian who is about to mount a particularly steep set of stairs, the aphorism feels a bit ominous. But as Adickes, with one arm wrapped around a companion’s, shuffles safely to the top, it’s easy to write the adage’s delivery off as one of the waggish artist’s characteristically good-humored jokes.

Adickes was born in 1927, before the invention of Scotch tape and canned beer. Although he now finds himself in a much different world, his quips are still timeless and effortlessly delivered.

At 97, Adickes maintains an output that’s as prolific as ever. He spends most days working on new art pieces in his home studio.

“The jokes, especially, are so ingrained in his psyche that he’s still very good with that,” says Linda Wiley, 71, Adickes’s longtime life partner. “Early on he learned that if you knew jokes, you could have a friend anywhere. So that’s his whole shtick—meeting people, being charming with people, and putting other people at ease. It really is a part of him almost as much as his art.”

And his art is very much a part of him. It’s hard to find a Houston creator more prolific than Adickes. He’s a painter, a sculptor, a musician, a skilled businessman, and an all-around virtuoso. Although not all Houstonians know his name, they’ve surely seen his work around town. The 67-foot-tall Sam Houston statue in Huntsville, where Adickes was born, is one of his creations, as is the famous statue of the Beatles on loan to 8th Wonder Brewery in East Downtown, and the 36-foot-tall (and 21-ton) Virtuoso sculpture next to the Lyric Tower building. That “We love Houston” sign that has spent the past decade popping up all over town? That’s also Adickes.

Towering over the presidential busts in the courtyard of Adickes’s workshop is a ginormous statue of Charlie Chaplin. We think it would also look great at the Orange Show’s Smither Park.

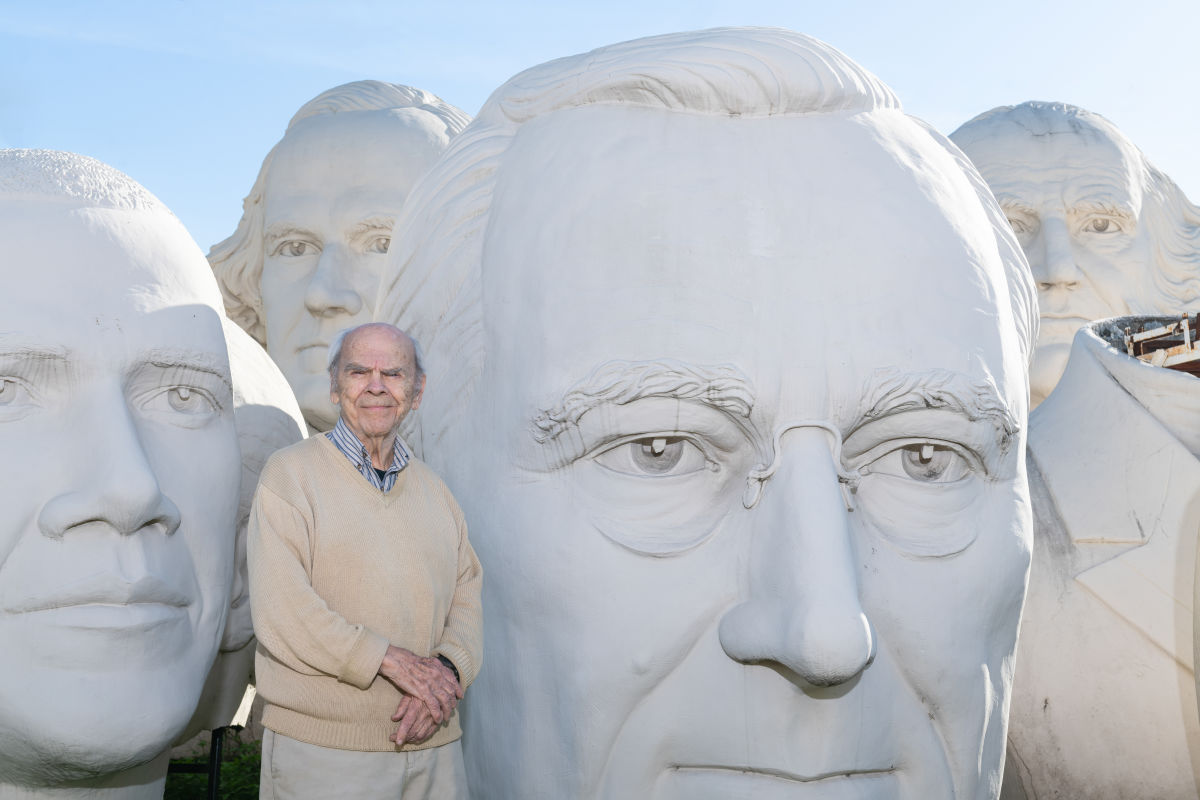

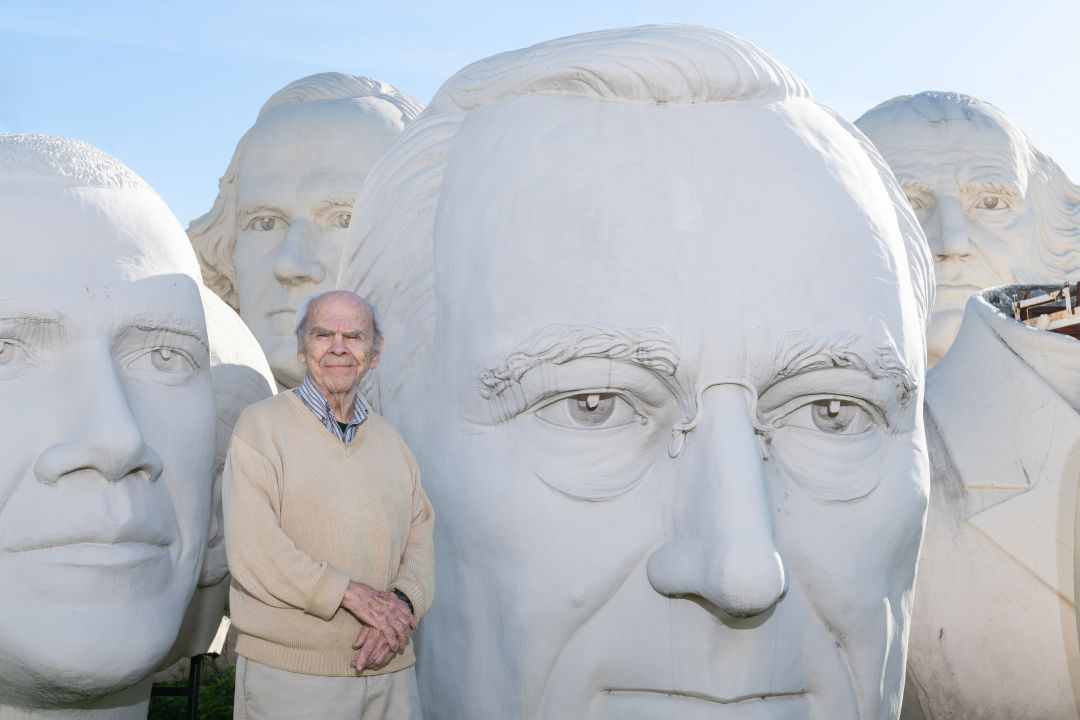

Oh, and then there’s all those president heads. He has 43 of them currently resting outside his Nance Street studio, covering all the presidents except Trump and Biden. Perhaps you’ve driven past them on your way to Saint Arnold Brewing or Last Concert Café. George H. W. Bush and his son, George W. Bush, modeled for theirs in person—Bush 41 at the White House and Bush 43 at Adickes’s Houston studio. “I did a lot of research. I got books on each one of them. They’re pretty accurate,” Adickes says.

He’s also completed an uncountable number of paintings through the course of his more than 80 years as a working artist, including three famously bought by Elvis Presley that once graced the walls of Graceland. While there isn’t a David Adickes museum in Houston (yet), Wiley says the closest thing to it is Reeves Art and Design in Montrose, which has a small collection of his work upstairs.

President George H. W. Bush modeled for his bust in person at the White House.

During a recent visit to Adickes’s Nance Street workshop, the scope of his eight decades of work was on full display. Across the walls hung paintings in different styles, and busts of endless variety were spread on shelves throughout the space. Some are small enough to be picked up by a strong set of hands, and others, like a giant half-finished bust of Abraham Lincoln, are large enough for a person to climb inside—one of the easiest ways to get inside the head of a president, the artist jokes. Adickes, who visits the workshop as often as he can (he works mainly from his home studio these days), led his guests that day on a spelunking adventure as he explored every nook and cranny of the shop, excitedly telling the stories behind each of the pieces as he came across.

Adickes’s Big Alex telephone sculpture features the face of Alexander Graham Bell. Since its construction in the 1980s, it’s traveled all over Houston.

Adickes’s journey from his humble upbringing in Huntsville to one of Houston’s most well-known artists began at the tail end of World War II.

“Remember that one?” Adickes asks jokingly. “It was in all the papers.”

Like many young men of that time, Adickes joined the military. Although he wanted to study aerial photography in Denver at the end of his air force boot camp, Adickes ended up reporting to a base in Fort Totten on Long Island, where he was assigned to a flight crew that regularly flew back and forth between New York and Paris. Each trip allowed about three days of downtime in the City of Lights, and they were impactful experiences for the budding young artist.

“That’s when I first saw Paris,” Adickes says, recalling the awe he felt as a young man from Huntsville at the sights and sounds of the French capital. “That really changed my life.”

Although Adickes ended up majoring in math and physics in college, he put his GI bill to better use afterward by returning to Paris to study at a school started by Fernand Léger, the celebrated French painter, sculptor, and filmmaker. While there, he met Herb Mears, a fellow American painter, with whom he would later establish a short-lived art school in Houston. At the conclusion of a gig teaching art at the University of Texas at Austin, Adickes found himself traveling abroad again, this time for two years. During his travels he met and became close friends with celebrated American author James A. Michener, and journeyed with him across Japan and multiple other countries.

While taking a road trip from France to Portugal during this period abroad, Adickes met Salvador Dalí in Spain, on the beach in front of his home, an experience he’s always eager to retell, especially the part where he caught a glimpse of Dalí’s, erm…“other paintbrush.” Adickes, who would later that day be given a personal tour of Dalí’s workspace, recounts how he watched the surrealist painter descend a set of stairs on his way to the beach for a swim. Dalí, with his swimsuit draped over his shoulder, made the journey in a terry cloth robe—minus the robe tie for modesty.

Adickes’s workshop is the setting of a continuous constitutional convention thanks to all the presidential busts gathered there.

Like many people in their later years, Adickes relishes in stories like this, retellings that allow him to relive some of the high points of his life. Although they still flow easily out of him, Adickes says his short-term memory occasionally falters, as is to be expected from someone who is pushing 100. His ever-present humor makes it hardly noticeable.

“I put all of my memories in this memory account, and it got foreclosed on,” he says.

He recently told Wiley that he’s been having some difficulty with walking and is worried his muscles are weakening, to which she says she responded, “Show me another 97-year-old who can walk like you do.”

Wiley, a flutist, music teacher, and author who recently released her first album, met Adickes in the early ’90s while he was working on his Sam Houston statue in Huntsville, and they’ve been inseparable ever since. Although she says they’re now living a bit more of a low-key lifestyle, Adickes’s output is as prolific as ever. Most days, he can be found whittling away on new art pieces in the upstairs studio of their River Oaks home, which he can conveniently access by way of an elevator.

Adickes was good friends with painter Herb Mears and celebrated author James A. Michener. He also once met Salvador Dalí in Spain.

“He goes there practically every day and does something,” Wiley says. “Creating art for David is like breathing. I mean, it’s not just what he does, it’s who he is.”

Adickes’s inner drive is relentless, and although he’s at the age when most people would be content busying their hands through the skillful placement of mah-jongg tiles or lazing up on a beach somewhere, he still opts for paintbrushes and clay. Don’t ask him if he’s been busy planning his retirement party.

“Retire? I’ve checked my tires, and I’ve got 30,000 miles left on them,” Adickes jokes. “No. I’ll probably work until the day I go, because it’s fun. It’s what I want to do. My goal is not to live forever, but to create something that will.”