In the 1890s, artists, designers, and architects across Europe rebelled against the enduring dominance of art standards from centuries past. Attempts to emulate the old masters gave way to abstraction, experimentation, and individual expression—with regional variations: France saw the birth of Art Nouveau; Germany, the Jugendstil; and in Austria, there were the Vienna Secessionists.

How did the Vienna Secession start?

The Vienna Secessionists: (back row from left) Carl Moll with hat and stick; Josef Hoffmann behind Moll; Gustav Klimt; Alfred Roller with hat and mustache; Kolo Moser (ca. 1898). Photo: Imagno/Getty Images.

Rebellion came naturally to groundbreaking artists in Vienna. The city’s Ringstrasse, which runs along its medieval walls, is packed with historic or history-inspired buildings that leave little to no room for contemporary, truly original architecture. From its neoclassical parliament and neo-gothic city halls to neo-baroque apartment complexes, Vienna was one giant tomb.

Also located on the Ringstrasse was Vienna’s Kunstlerhaus, a Renaissance-style exhibition hall that for many years served as the only institution through which artists could display their work. The Kunstlerhaus was dominated by conservative bureaucrats who rejected any submissions that did not stick faithfully to the accepted, “academic” style.

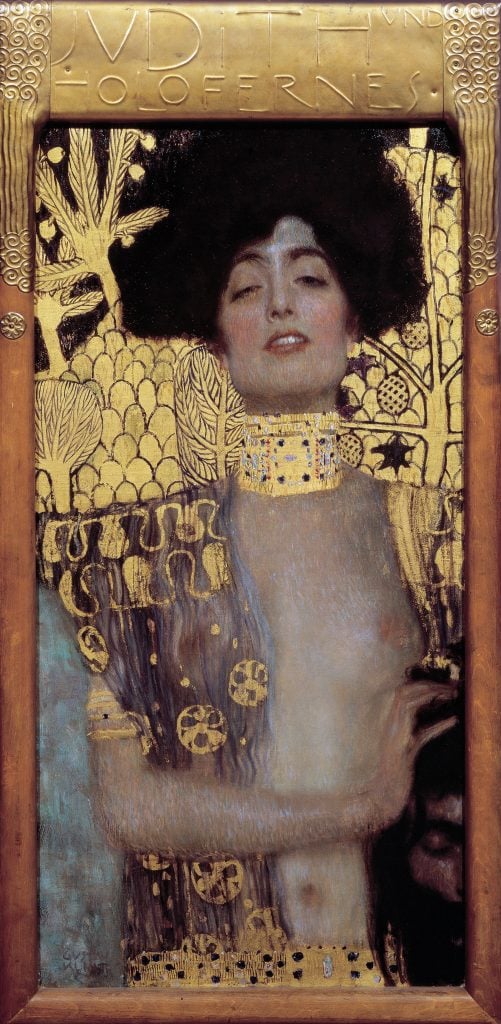

Gustav Klimt, Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1901). Photo: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

United under painter Gustav Klimt, Viennese artists who did not agree with the tastes of the art establishment broke away from the Kunstlerhaus to found their own society in 1896, which took after the so-called Secession movements that had previously taken place in Munich and Berlin. Their break with the Kunstlerhaus was cemented when, in 1897, the institution’s leaders opted to censure the Secessionists, crushing any chance of reconciliation between the two groups.

Why haven’t I heard of the Vienna Secession before?

The Secession Building, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, in Vienna, Austria, 2015. The Secessionist motto is spelled out in gold letters above its entrance. Photo: Alan John Ainsworth/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Not only is the Vienna Secession much less well known than other turn of the century art movements like Jugendstil or Art Nouveau, but notable members of the Secession, including Klimt, are often talked about in isolation from the societal currents in which they swam.

One reason for this neglect is the Secession’s lack of a style or ideas that tied the work of its members together. Interestingly, though, this lack of programming was precisely what the movement was all about: breaking free from the creative restrictions of the Kunstlerhaus. The movement’s motto, quoting art critic Ludwig Hevesi, read: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst. Der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To every age its art, to every art its freedom).

What do Secessionist works look like?

Cover for Ver Sacrum magazine, book 4, designed by Kolo Moser (1899). Photo: Imagno/Getty Images.

Drawing inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement in England and the United States, the Secession manifesto rejected industrialized mass-production in favor of collaborative, handmade artisanship bordering on Gesamtkunstwerk. Klimt, as evidenced by his drawings for the group’s magazine, Ver Sacrum, argued art should be individual, expressive, and critical rather than transcendent and commemorative, a means of questioning the present rather than honoring the past.

In this, the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), established by architect Josef Hoffmann and artist Koloman Moser in 1903, sought an artisanal approach to the decorative arts from jewelry to leather goods. “The materials, the tools, and sometimes the machine,” wrote Hoffmann of the workshop in 1928, “are our only means of expression.”

Silver pendant designed by Josef Hoffmann and made by the Wiener Werkstaette (ca. 1905). Photo: Imagno/Getty Images.

The Secessionists, while borrowing heavily from Jugendstil and Art Nouveau, would blaze their own aesthetic paths, favoring geometry, symmetry, and repetition. From this heady, progressive brew would emerge paintings including Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–08); buildings like Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Secession Building, the Secessionist’s alternative exhibition hall; and avant-garde decorative art pieces by Hoffmann.

What happened to the Secessionists?

The fate of the Vienna Secession was the same of many an art movement: the rebellious, outside voice became the dominant, pro-establishment voice, before the cycle repeated, with another generation of young, ambitious artists breaking from their reluctant elders.

After nearly a decade and 23 exhibitions, the Secessionists ripped themselves in half. On the one hand was the “Klimt group,” which encouraged the inclusion of applied arts and other mediums in their exhibitions. Another faction held that painting was superior over art forms and should be kept separate from them.

The split, which had been growing for years, was finalized in 1905, when Moll was in talks with a private gallery to host a Secession exhibition. The Klimt group regarded this as selling the movement’s anti-industrial and anti-commercial movement and, after losing a society-wide vote to determine whether Moll would be allowed to accept the deal, resigned, causing membership to drop significantly.

Why are we still talking about the Vienna Secessionists?

Egon Schiele, Kneeling Female in Orange-Red Dress (1910). The model for the work was the artist’s sister, Gertrude Schiele. Collection of the Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Because the group would leave an outsized footprint in styles including Art Nouveau and Expressionism in Austria, the latter prominently led by artists including Egon Schiele (a Klimt protege) and Oskar Kokoschka, who were associated with the group in its later years. The Vienna Workshop, which closed after the stock market crash of 1929, would further shape movements from Bauhaus to Art Deco.

Olbrich’s Secession Building, one of the earliest spaces dedicated to exhibiting contemporary art, would weather World War II to remain the only venue in Austria to be managed by local artists. Its facade continues to bear the Secessionists’ motto in large gold letters.

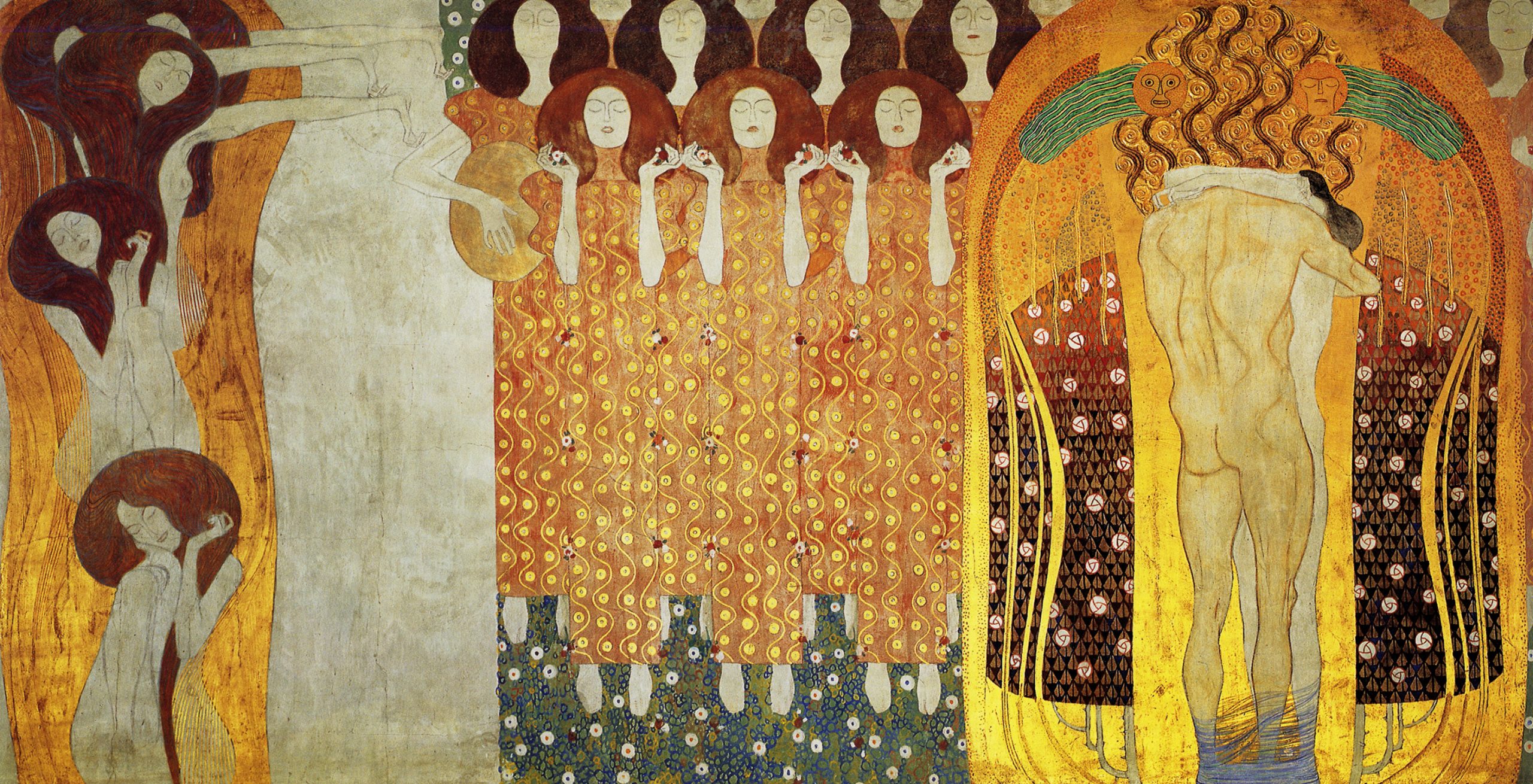

Main room in the Secession Building with the Beethoven Frieze by Gustav Klimt and Max Klinger’s Beethoven statue, 1902. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

One of the building’s galleries has been specially designed to display Klimt’s monumental Beethoven Frieze, created for the 1902 Secessionist exhibition dedicated to the German composer and acquired by the Republic of Austria in 1973. Though derided as obscene by the public upon its unveiling, the sprawling mural is now celebrated as a masterpiece of Austrian art. In a further sign of how the country has come to embrace a once-subversive movement, the frieze was commemorated in 2004 in a €100 gold coin dubbed the Secession Coin.

For as long as there has been art, revolutionary movements have continually reshaped its creation and perception. Artcore unpacks the trends that have shaken uptoday’s and yesterday’s art world—fromthe elegance of 18th-century Neoclassicism tothe bold provocations of the 1990s Young British Artists.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: