The hottest ticket at the Independent art fair, now underway in New York, may just be at White Columns’s booth on the seventh floor, where ex-art dealer and now artist Joel Mesler is painting visitors’ portraits. They’re priced at a modest $250; even on my freelance writing income, I can afford that, I thought, so I threw on a patterned tie and pocket square (to up the degree of difficulty for the artist) and showed up as the fair opened at Tribeca’s Spring Studios.

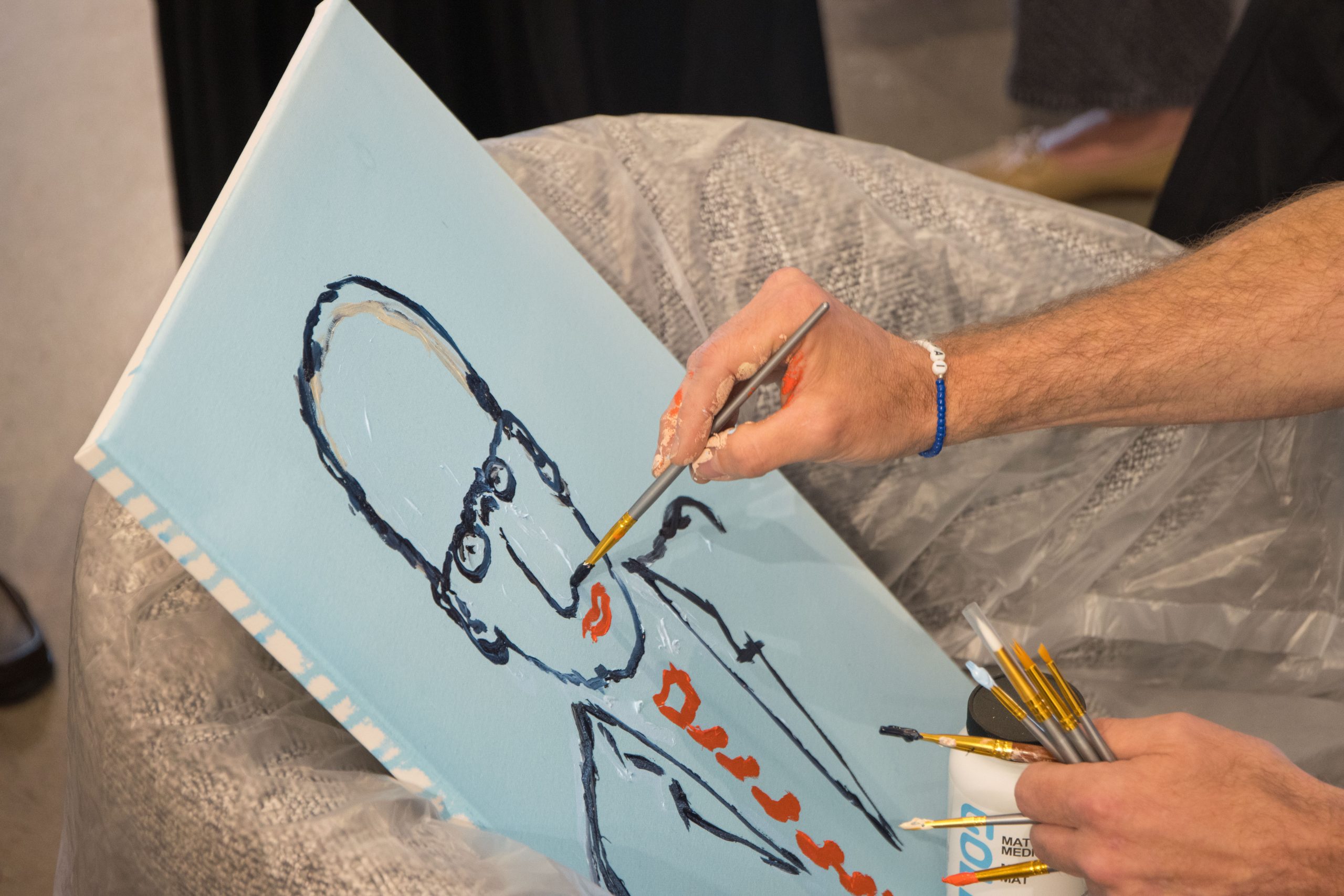

What I found when I got to his work station, a simple bench by a window looking down onto the sales floor below, wasn’t exactly what one might expect. No easel or palette. No smock, just gray chinos and a blue jersey. The canvas sat propped on a chair that was covered with a sheet of plastic, and his palette was just a disassembled cardboard box sitting on another cardboard box. I sat on a fairly grubby director’s chair; Mesler had just pulled it all out of a nearby mechanical room.

“There’s something about not setting up a traditional easel,” Mesler said. “It’s almost like I came in off the street, like someone just let me in. All these other people paid to be here! I try not to put in that much preparation.”

Exterior of the Independent Art Fair in New York, 2024. Photo: Elvin Tavarez.

When I showed up at 11 a.m., when the VIP preview was officially opening, Mesler had already painted two portraits (I was told I would be first, but whatever), and he would be banging them out until 8 p.m., when the fair closed, making this a bit of an endurance-heavy performance piece.

“Matthew Barney is just one of my perfect heroes,” Mesler said. He noted that Barney’s early “Drawing Restraint” performances are a bit of a model for him; the “crazy conditions” of trying to work in the hectic surrounds of an art fair are all part of the thing. The conditions have been crazier, in some ways, at past sessions; if you were taking the 35th Street Ferry to Randalls Island for Frieze New York in 2019 (we miss you, big tent!), you could pay $100 to sit for him on deck. He spent half the time barfing, seasick, in the bathroom. Not exactly Matthew Barney, but still, a true commitment to the bit.

But let’s back up a moment. Who is this artist, anyway?

Mesler has had a slightly circuitous trip in the art world, trying his hand as an artist in Los Angeles in his early days, then becoming, as he once described himself, a “middle-class dealer” in L.A. and then in New York. He had great success at scouting talent; he was among the first to show artists like Loie Hollowell (now with Pace), Rashid Johnson (now with Hauser and Wirth), and Henry Taylor (also Hauser and Wirth). He was dismissive of dealers who complain about having their artists poached. “It’s shocking that you’re surprised,” he said he would tell them, since art galleries are really just stores, not so much cultural institutions. “You’re brand-building just like I am.”

He started painting as a hobby in 2015 and showed what then-Artnet News editor Andrew Goldstein described as “self-satirizing” paintings at NADA Miami Beach in 2016. It all started in an offhand way: “I had sold out my booth of paintings of my own work at NADA two years ago and while I was talking to [publicist] Adam Abdalla about being bored with nothing to do for four days, he suggested painting portraits for people for me to stay busy. The rest is history.”

Brian Boucher sitting for a Joel Mesler portrait at the Independent Art Fair in New York, 2024. Photo: Elvin Tavarez.

And what a history it has been! He has had solo shows at top-shelf galleries from David Kordansky in Los Angeles to LGDR (from when Dominique Lévy, Brett Gorvy, and Amalia Dayan were briefly in business with Jeanne Greenberg-Rohatyn) in London and Palm Beach. His painting To Life (2020) went for a whopping $907,200 against a $150,000 high estimate at Christie’s New York in 2022.

Sometimes, when preparing to open a new gallery or mount a show, he releases a low-key-brilliant mockumentary-style promotional video in which art-world honchos like Gagosian director Adam Cohen, advisor Benjamin Godsill, and Rashid Johnson appear, alternately endorsing his projects, suggesting future steps, or (and Cohen is especially good at this) singing his praises while also dryly undercutting him. He himself guilefully presents whatever new thing he’s up to, intercut with videos of him living his newly sober life with his wife and children.

If he was a modest success before, he’s made it to the big time now, with his largest show yet opening June 6 at Lévy Gorvy Dayan in its grand Beaux-Arts townhouse on New York’s Upper East Side. Its title, “Kitchens are good rooms to cry in,” refers to the moment when his parents told little Joel they were divorcing. That was when things started to go wrong for him, he said; he later descended into drug addiction but is now sober. Mesler’s LGD outing will be quickly followed by a show at Château La Coste in Aix-en-Provence and Pool Party, a public installation at the Rockefeller Center ice rink, both of which open in July. (Meanwhile, both at Independent and at its townhouse gallery on New York’s Upper East Side, Lévy Gorvy Dayan is showing entrancing paintings by British painter Allison Watt.)

Before I got a chance to sit for my portrait this morning, New York contemporary art collectors Susan and Michael Hort had their turn, pushing my appointment back a bit, but you cede your place to art-world royalty when you have to. “They saved me as a dealer,” Mesler said. I watched as he hastily daubed while chatting amiably with the couple. At first he painted them on a single canvas, but a few minutes in, he stopped. “Not up to my standards!” he said. This was a unique event. “I’ve never done a re-do!” This time he opted for a portrait of Susan only, her trademark shock of red hair prominent on the canvas. He was done in two minutes, I swear.

Joel Melser paints Susan and Michael Hort at the Independent Art Fair in New York, 2024. Photo: Elvin Tavarez.

My turn! By now, things were getting a little chaotic. “I was next!” cried out another aspiring sitter. But he agreed to wait.

Mesler and I talked about past portrait sessions. The last time he did this, he painted until 3 a.m. at a wedding that had more drugs than a Burning Man festival, he said. People were trying to get their portraits done who couldn’t even stand anymore, he recalled, and physical altercations were breaking out over spots in line.

Mesler looked back on his days behind the desk at an art gallery, which is where I first got to know him, many years ago in Lower Manhattan. “I wake up every day thankful that I don’t have to be an art dealer,” he said, while surrounded by dozens of dealers hawking their wares. He did, though, say how happy he is that the artists he showed have gone on to great things. Recalling Henry Taylor’s recent Whitney Museum blowout, he acknowledged being “so happy Henry is finally having his due.” He recalled the days when Taylor’s painting setup was even more modest than his own.

Brian Boucher sitting for a Joel Mesler portrait at the Independent Art Fair in New York, 2024. Photo: Elvin Tavarez.

Asked who were his heroes in addition to Barney, Mesler cited painters R.B. Kitaj and, especially, Ben Shahn. “He got me into art,” said Mesler. “He was all about the opposite of scarcity. He wanted to get his work out into the world.”

Over the 15 minutes that I sat for the painting, things got louder and louder as more people streamed into the fair and made their way to the seventh floor, perhaps having seen Mesler’s Instagram post from the previous day announcing his portrait sessions. His studio manager, Maggie Merrell, did her best to keep things moving along, but she acknowledged that the chaos is part of the package. “Sure,” she said, “we could do Calendly appointments.”

Brian Boucher and Joel Mesler with the completed portrait. Photo: Elvin Tavarez.

Then, the moment of truth: he picked up his painting and turned it toward me. My blazer is outlined in blue against the pale background, and the salt in my salt-and-pepper beard is bright white. A photorealist he’s not; in fact, paintings have been orphaned in the past when, after being set aside to dry for a few hours, no one looking at them could recognize the sitter. I would probably have to stand next to the painting for you to know it was me, but I love it, of course. My horizontal-striped knit tie had turned out looking more like a lollipop, Merrell said, or a barbershop pole.

I’ll hang it with pride in my home. I can’t wait to pick it up.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.