As much as they are works of art, the assemblage-like paintings of Raymond Saunders are works of archaeology.

In “Post No Bills,” a four-decade overview of his work at two galleries — David Zwirner in Chelsea and Andrew Kreps in TriBeCa — one gets the sense that the artist is excavating his own paintings, literally digging beneath their surfaces to expose hidden layers.

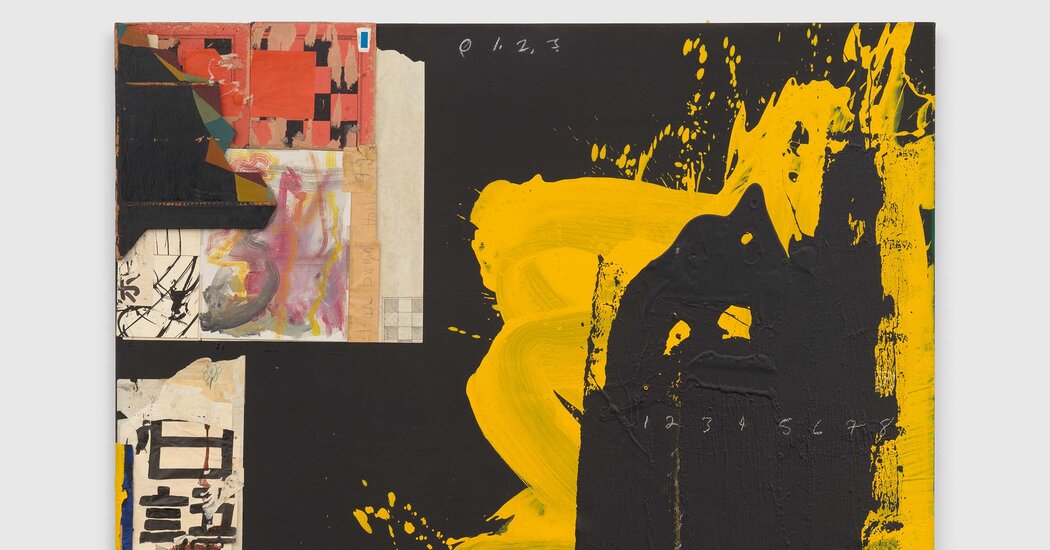

In “Saturdays of Black Color and Habitual Gestures” (1987), for example, Saunders mounts scraps of discarded posters, newspapers and street signage on canvas and then tears at them, yielding a distressed texture of buried paint and paper. In “Pittsburgh ’07-11” (2007), a thick layer of white paint has dried and cracked like a desert floor, its fissured topography revealing black gesso (a primer that makes canvasses smoother and less absorbent). There is life beneath the surface, and it is not content to stay there.

“Post No Bills” is a sprawling map of Saunders’s searching mind and hard-to-categorize work. The artist, now 89, draws from the improvisatory impulses of jazz, the power of Abstract Expressionism, the eclectic excessiveness of assemblage and the academic classicism of Renaissance painting.

His cartwheeling and singular aesthetic strategy teases the eye in “Places Near and Far” (1986), a work in which the precision of minimalism rubs up against the bombast of painterly marks whose wild coils and curves evoke Abstract Expressionism. Found materials, including street signage rulers, ornithology illustrations and children’s drawings, festoon the canvas, mingling with hurried chalk annotations and prays of gestural brushwork resembling graffiti.

Paintings like “Drawing a Still Life” (1987) and “A, B, See” (1996) reveal Saunders’s penchant for seemingly out-of-place art historical motifs, like elegant chalk drawings of Baroque still-life-esque pears and flowers. There is no easy way for the viewer to make sense of this motley group of elements, and it is this difficulty that makes the paintings so powerful.

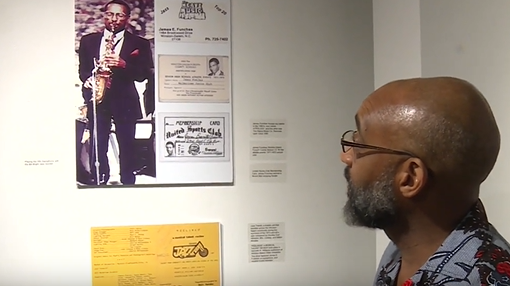

The exhibition, curated by Ebony L. Haynes, the director of David Zwirner’s outpost 52 Walker, also illuminates Saunders’s way of speaking to the broader social and visual world. The exhibition’s title, borrowed from a 1968 work on display, is a familiar part of the urban landscape, evoking the city walls worn down by cycles of illicit yet obdurate flyposting, removal and reposting.

Here, such urban surfaces are analogized to the rough and variegated texture of Saunders’s canvases; both are teeming with layers of articulation and erasure, both are archives of their own histories.

In several paintings, signs reading “Post No Bills” share the canvas with abundant brushwork and exuberant collages that disobey these directives of orderliness. Amplifying this renegade sensibility, Haynes has plastered some of the gallery walls with vinyl sheets featuring blown-up details of Saunders’s canvases, mucking up the usual austerity of the rooms.

Saunders rebels beneath the surface of his paintings, too. Throughout his career, he has asked where a painting starts — what exactly is a blank canvas? Rather than accepting white as the neutral starting point for painting, Saunders often builds dizzying assemblages up from a base of black gesso.

While some viewers may think such gestures are political, Saunders has long pushed back against a reductive linking of an artist’s work to their racial identity. In “Black Is a Color,” a 1967 essay, he rebuffed the ambitions of the Black Arts Movement — the cultural cousin of Black nationalism — as an unacceptable restriction on artistic freedom. Suggesting that Black identity solely defined one’s work was a gross error, he wrote, and by separating the two, “we get clear of these degrading limitations, and recognize the wider reality of art, where color is the means, not the end.”

This insistence that black is, indeed, a color reverberates from the paintings in “Post No Bills.” In them, we witness a lifelong exploration of the pleasure, variety and depth of black. At times it glistens with sleek sheen, at others it wrinkles like skin, and at still others it is matter-of-fact matte.

The black background also suggests another site of investigative inquiry: the blackboard. Saunders has taught at universities including the California College of Arts and California State University, Hayward (now California State University, East Bay), and his painting career is unthinkable without the inquisitive buzz of the classroom. In “Flowers From a Black Garden, no. 51” (1993), a miniature blackboard is affixed to the canvas. Coming from an educator’s mind and soul, Saunders’s work teaches our eyes how to ask questions, how to dig deep.

Raymond Saunders: Post No Bills

Through April 6 at David Zwirner, 519 & 525 West 19th Street; davidzwirner.com; and Andrew Kreps Gallery, 22 Cortlandt Alley, Manhattan; 212-741-8849; andrewkreps.com.

This review is supported by Critical Minded, an initiative to invest in the work of cultural critics from historically underrepresented backgrounds.