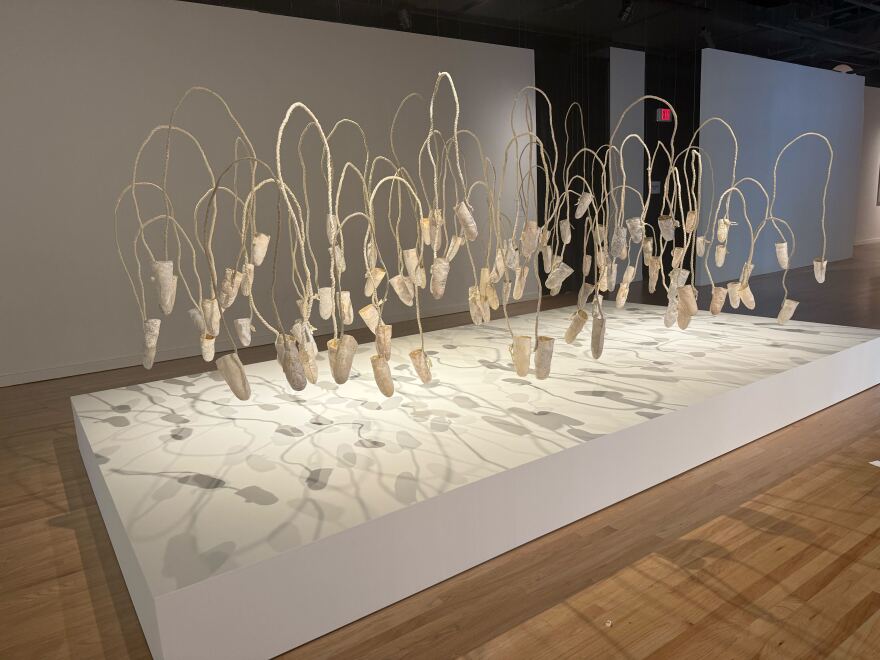

Cocoons hang from the ceiling in a gallery at Capitol Modern in Downtown Honolulu. Light casts a shadow onto a white platform, where they appear entangled in the web-like art piece.

From the surface, the cocoons are separated by their pods. But beneath it, they’re all connected.

“There’s this movement of shadow and line that one loss affects many,” said Sonya Kelliher-Combs, the artist behind “Idiot Strings.”

Kelliher-Combs is one of 49 artists whose artworks are on display at the Hawai‘i Triennial, the largest thematic art installation in the state with locations across O‘ahu, Maui, and Hawai‘i Island.

The 78-day event brings artists from around the world, including those from Indigenous populations. This year, some artworks created by Indigenous people embody intergenerational trauma and suicide in communities.

Kelliher-Combs, of Iñupiaq and Athabasca descent from Alaska, has been working on her piece “Idiot Strings” for more than 20 years. She created it in memory of her three uncles who died by suicide.

“It’s something that people don’t talk about, especially in native communities because of colonization and the church,” she said. “It’s considered shameful.”

She added that she wanted to remember her family and friends “who had fallen to this epidemic in our populations.”

Kelliher-Combs said the strings are tethers used to hang mittens. She said the attached sculptural pockets suggest an absent body.

She created the piece using commercial sheep rawhide, which is rigid when it dries. Then, she sews and stuffs it to create cocoon-like mittens. Once they dry, she paints them using acrylic.

In addition, the ropes are made of sheep wool, and the final step is dipping them in beeswax.

Kelliher-Combs underscored the process of creating her work. She often spent time working by herself or accompanied by family and friends.

“We need to talk about this hard stuff and bring it to light so people can move on from it and heal,” she said.

A legacy left behind

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among Indigenous communities in the U.S., according to a study from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. The rates increased by 40% between 2010 and 2020.

The late Native Hawaiian master carver Rocky KaʻiouliokahihikoloʻEhu Jensen died by suicide in 2023. Several of his carvings, which are ki‘i or images representing Hawaiian Gods, are on display at Capitol Modern.

In the 1970s, he and his wife, Lucia Tarallo, established Hale Nauā III, a Native Hawaiian arts organization that supports Native Hawaiian artists.

Jensen was described as a contemporary artist who used his art to educate his community. Tarallo said Jensen was an active critic of art institutions that refused to purchase Native Hawaiian art.

His artworks capture images of what Hawaiians looked like prior to the colonization of the islands.

Tarallo said Jensen was diagnosed with bipolar depression.

“He dedicated his life to not only his art but controlling himself,” she said.

Tarallo said Jensen left a legacy without realizing he left it in the first place.

“He felt that he had failed,” she said. “He died feeling that. Even if one person in the audience was listening, that was a boon to our soul. To Rocky, he wanted all of his people to listen.”

Tarallo said his last words were: “My culture let me down.”

Dealing with intergenerational trauma

On the second floor of Davies Pacific Center, a video shows a woman washing three white walls. There was nobody talking — just the texture of sound.

Nanci Amaka, an interdisciplinary artist from Nigeria, is the artist behind “Cleanse | Three Walls.”

The art piece pays homage to Amaka’s mother, who was killed in Nigeria when Amaka was 4 years old. She didn’t find out about her mother’s death until she was in her 20s, after she reconciled with her mother’s side of the family. That was after she and her family migrated to the U.S. from Nigeria in the 1990s.

Courtesy Nanci Amaka

/

“I carried around a lot of anger,” she said.

Growing up, Amaka’s mother was never mentioned in her household. In fact, her father got rid of all the photos of her.

She said she didn’t pry about how her mother was killed, but she often has bad dreams about it. She dealt with her mother’s death on her own — by not talking about it.

Amaka started her piece in 2017 at the Ward Warehouse before it was demolished. At the time, she was pregnant with her daughter. Three tripods were set up to record her.

She metaphorically cleans the space, adding that it’s minimal and quiet.

When the audience views the piece, she wishes to provide a quiet space for them to reflect on their trauma and heal from it.

“They have an excuse to think about the people they’ve lost and engage with those memories,” she said. “They can take a deep breath and allow themselves to feel whatever they felt in that moment.”

Behind the theme Aloha Nō

Noelle Kahanu, a co-curator of the Hawai‘i Triennial, said the artworks fit around the theme of Aloha Nō.

She said the artists draw attention to the harms and injustices happening in various communities.

“It’s about how artists within our midst are identifying the cracks and fractures that surround us,” she said.

Instead of the Hawaiian diacritical mark kahakō over the “o”, Kahanu said it’s replaced with pewa, a butterfly-shaped patch often used in woodwork. Pewa is often used to seal a crack in a ‘umke bowl.

She used the artists as examples.

“They’re offering wellness or healing through the pewa that we can take away from these exhibitions and the works of these artists with a sense of hope and not despair,” she said.