In 1987, Joan Didion wrote a series of articles for the New York Review of Books that were then collected into the book “Miami.” The acclaimed journalist captured the “tropical capital” during a period of dubious notoriety — post Mariel and McDuffie, in full-blown cocaine-cowboys, glamour-and-carnage swing. She saw the city with the fresh perspective of a well-informed outsider and nailed its ironies in microscopic detail: empty plazas downtown; condos walled off or guarded by moats, for “times of unrest”; bankrupt developments. “A tropical entropy seemed to prevail, defeating grand schemes even as they were realized,” she wrote.

In writing “Miami,” the author of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The White Album” did what journalists do: She parachuted in, then immersed herself for months. A California native, Didion lived in New York, but retained her Sacramento-bred interest in the edges of the New World. She homed in on Miami’s Latin community, particularly Cuban exiles, because she had a deep interest in the global south; she previously wrote a book about the war in El Salvador.

Didion was a thorough researcher. She went to Dolphins games, courtrooms, political meetings, morgues. She interviewed politicians, developers, criminals, journalists. Mitchell Kaplan, a man whose grand schemes of making Miami a literary hotspot have far from failed, drove Didion around town one day. “We spent an afternoon in my car, basically, and she was quiet but really lovely and really engaging, asking questions,” the Miami Book Fair founder told me. “But mostly she was observing.”

Many of her observations were original and prescient. She pinpointed Miami’s unique role as the center of a circle from Europe to D.C. to Bogota to Havana. She realized that Latin Americans were the city’s emergent power base and its increasingly dominant culture. And she narrated it all from a quintessentially lacerating Didion point of view: unsentimental to the point of grimness, what the writer Mike Davis dubbed “sunshine noir.”

In retrospect, the fault lines of Didion’s outsider perspective are evident. She tallied the body counts and the squandered public money, but failed to savor the cultural bounty. She penetrated the political societies of the exile community, but not the dance clubs.

In 2001, I moved to Miami to write for the Miami Herald. Many of the places Didion wrote about had indeed been defeated or were unrecognizable. I bought a copy of “Miami” at Books & Books and devoured it as absolutely necessary, but also already dated. I recognized the tropical entropy, the corrupt privatization that Didion nailed as being “on the southern model.” But I also witnessed dreams being realized: DJ Le Spam spinning global beats at Little Havana’s Fuacata, bookworm bacchanals at the Miami Book Fair, taggers turning Wynwood into an outdoor art fair.

I found a different Miami because I was looking for the perfect beat, just as Didion viewed the city as a case study in what writer David Rieff said was her great subject: empire. This is another thing journalists do: We bring our baggage to the byline. The inevitability of subjectivity is one of the lessons her writing teaches. “I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind,” she wrote in “The White Album.”

Didion died in 2021. But her impact seems to grow, not just on writers, but on artists, musicians and filmmakers. The critic Hilton Als built an art exhibit, “What She Means,” around her life; it’s now at the Perez Art Museum Miami. The first song on the new Olivia Rodrigo album gets its title from a Didion story in 1967 on Haight-Ashbury. Greta Gerwig’s movie “Lady Bird” opens with a Didion epitaph: “Anybody who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento.”

While researching Didion, I realized there’s an aspect to her work that gets lost beneath the withering one-liners and gimlet-eyed autopsy accounts. The woman who chronicled her husband’s death and daughter’s mortal illness in “The Year of Magical Thinking” loved flowers. They’re there in “Miami,” “the fallen frangipanis and crepe myrtle blossoms.” I believe it is this, Didion’s appreciation of beauty, that elevates her writing to be more than just a record of the world but the world itself. “In this mood Miami seemed not a city at all but a tale, a romance of the tropics, a kind of waking dream in which any possibility could and would be accommodated.”

I recognized that Miami in 2001. Maybe you do as well.

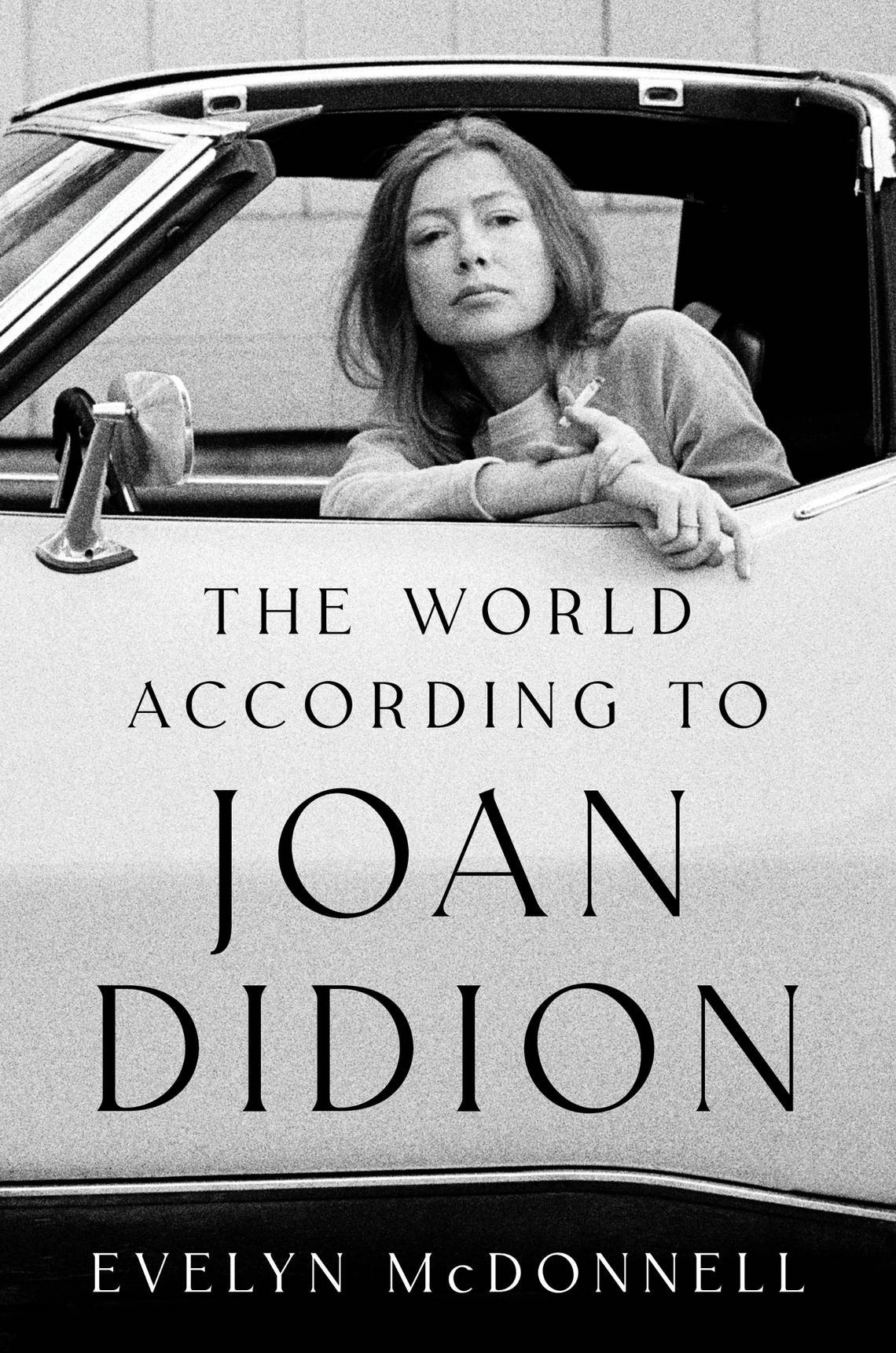

Evelyn McDonnell is a former pop music critic at the Miami Herald and the author of “The World According to Joan Didion.” She’ll speak about her book at the Miami Book Fair at 11 a.m. Nov. 19 and will interview Susanna Hoffs on at 6 p.m. Nov. 18. At 2 p.m. Nov. 20 , she’ll give a guided tour of the Perez Art Museum Miami exhibit “Joan Didion: What She Means.”