After more than 30 years of active involvement in Seattle’s art scene, Mary Ann Peters finally has her first solo museum show. Opened this month at the Frye Art Museum and titled Mary Ann Peters: the edge becomes the center, the exhibition features two bodies of work: the artist’s this trembling turf series — all 10 panels of which are being shown together for the first time — and a new, site-specific installation titled impossible monument: (gilded), which is a continuation of her impossible monuments work. For Peters, a second-generation Lebanese American artist, the Frye is a “perfect match,” for her,” she says. “I think some of the most adventurous work is happening there.”

Installation view of Mary Ann Peters: the edge becomes the center, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, June 15,

2024–January 5, 2025.

Photo by Jueqian Fang

A multi-award-winning artist with a laundry list of awards under her belt, Peters not only has a prolific output — she has fostered the local arts community and advocated for artists’ rights for years. She is a founder of Seattle’s Center on Contemporary Art and a former board member and president of the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression. Peters’ work, although primarily rooted in subject matter concerning the Middle East, is widely applicable in that it encourages viewers to look beyond information presented by mainstream sources about history, politics, and culture. Sparked by a 2010 trip to Lebanon with her siblings, this approach of digging deeper, or looking beyond the edges, has become a guiding force for Peters — and the catalyst for a big shift in her creative practice.

“We went to Lebanon and then the Arab Spring happened,” Peters recalls, “and it became quite clear to me that I didn’t understand that part of the world enough. In trying to educate myself I started following obvious sources, but then I got intrigued by archives, histories, and perspectives that weren’t represented in those sources.”

In the years after that trip, Peters returned to the Middle East and spent time in Europe and Mexico City, looking closely at the migration pattern of her family and thinking about the untold or censored stories of countless immigrants around the world. It was during one of these trips, a 2016 residency in Beirut, when the idea for her this trembling turf series started to emerge. “I was doing research at the Arab Image Foundation, which housed, I think at the time it was over 600,000 images by photographers and artists in the region,” Peters recalls. While looking through a book, she came across the allegation that there is a mass grave underneath one of the city’s posh golf courses. Given the tenuous and disputed nature of the information, Peters didn’t feel comfortable making work directly about the subject, but she started thinking more deeply about what lies under the surface of things—both physically and metaphorically.

“The science of locating the history of things that are buried is forensic anthropology and archeology,” the artist explains. “They use a device that skims the earth much like a sonogram and pulses where it comes across something solid.”

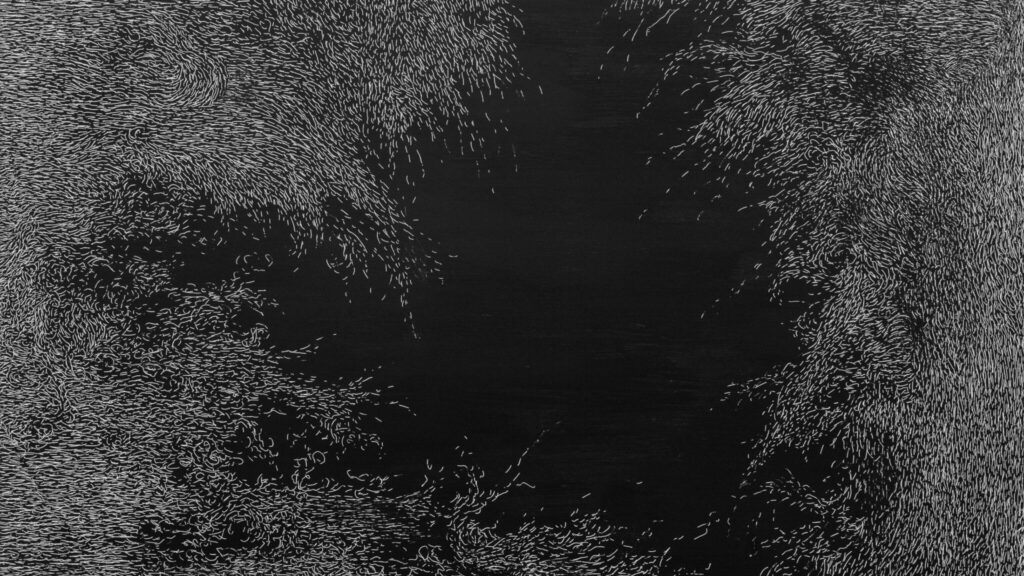

The resulting series, created over five years, consists of 10 large-scale works made with white ink on black clayboard. The marks, there are thousands of them within each piece, are similar to the pulses released during sonar imaging—from within their depths an image, an idea, an artifact emerges. Here, it’s more of an emotion than anything else. Peters captures voids, chaos, overwhelm, and sheer determination in her brush strokes. “The orientation is purposeful,” she says of the five-foot-tall by four-foot-wide rectangles. “Looking at them, the viewer can feel as if they can submerge themselves underground. I wanted to have each viewer find their spot in the piece and want more.”

Mary Ann Peters. this trembling turf (the hollow), 2021. White ink on black clayboard. 60 x 48 in. Collection of the Seattle Convention Center.

Photo Courtesy of James Harris Gallery. Photo by Rafael Soldi

Peters’ new work, impossible monument: (gilded), is contained within a cabinet-like form and holds a hodgepodge of symbols that tie back to themes of displacement, the meaning of homeland, and having—or choosing—to live away from the latter. Made with fabricator Joel Kikuchi, the installation is full of symbols: keys, survival blankets, and door plates all nod to ideas of home. “I included dozens of keys,” Peters says, “because the bottom line is that everybody wants to be able to open their front door, everybody wants their key. Most people when they leave their home they take their keys because they think that they will go back.”

Mary Ann Peters. impossible monument: gilded (detail), 2024. Wood, laminated survival blankets, glycerin, keys, keyhole plates, ribbons, aramid honeycomb, oval frame. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view of Mary Ann Peters: the edge becomes the center, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, June 15, 2024–January 5, 2025.

Photo by Jueqian Fang

Coordinated by Alexis L. Silva, a curatorial assistant at the Frye, Mary Ann Peters: the edge becomes the center is a poignant reminder that we should never mindlessly accept things at face value. Asking questions, getting second opinions, and looking to alternate sources always prove invaluable, especially when agenda-driven media are leading the conversations around global events. Beyond any messages gleaned from the work, Peters’ artistic skill is on full display. Meticulous detail and thoughtful materiality bring a haunting beauty to each piece.

“I hope that these pieces generate a curiosity about the part of the world I’m interested in,” she says. “I also hope that I’m making work that acts as a spark for people to take a chance on finding out more about things they don’t know.”