On June 2, María Luque noticed several of her contacts on Instagram posting about a form she had never heard of.

The form, Luque found out, had been sent to users in the European Union and the U.K. to give them the option to opt out of Meta’s plans to use public posts on Instagram and Facebook to train its artificial intelligence model. As an illustrator based in Argentina, Luque considered social media platforms vital for promoting her colorful hand-painted vignettes of everyday life. But she couldn’t find the form anywhere on her accounts.

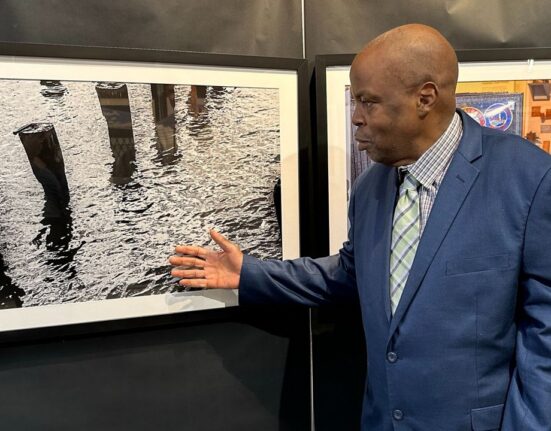

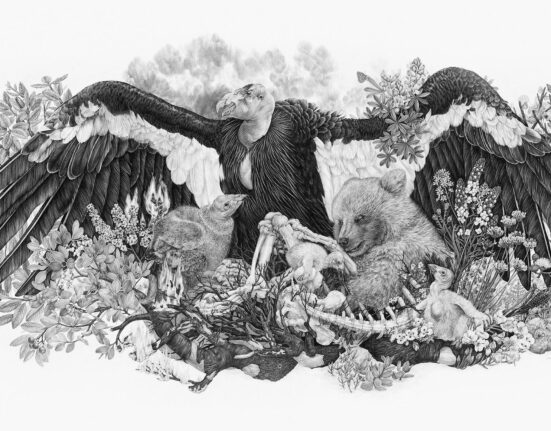

Instagram/@alzamonart

It didn’t take long for her to understand that only artists in Europe had been given the option to opt out. “We couldn’t find [the forms] because they weren’t available,” Luque told Rest of World.

Artists in Spanish-speaking Latin America — where AI regulation and privacy laws are outdated or nonexistent — are worried about the future of their work as Meta ramps up the training of its large language models by mining publicly shared content across its platforms. While the company gave its users in the EU and the U.K. the opportunity to protect their content — and has since paused its AI rollout there — most Meta users in Latin America will have no say in how the platforms use their content.

Rest of World spoke with nine Latin American artists, several of whom were unaware of Meta’s plans to use their content for AI-related purposes until June, when the company announced it had “sent more than two billion in-app notifications and emails to people in Europe to explain what we’re doing.”

“Instead of adopting broader protection measures for all, which would mean granting the same rights to Latin Americans as those in the European Union, these platforms discriminate based on location,” Agneris Sampieri, Latin America policy analyst at the digital rights group Access Now, told Rest of World.

A Meta spokesperson told Rest of World that the company will continue to build AI “responsibly” and that “using publicly available information to train AI models is an industry-wide practice and not unique to our services.”

Instagram/@panchopepe2000

In September last year, Meta announced the launch of new generative AI features, for which the company had mined the content on its platforms. It stated that “publicly shared posts from Instagram and Facebook — including photos and text — were part of the data used to train the generative AI models underlying the features we announced at Connect.” These features include a generative AI-powered search tool integrated into the Instagram app and an image generator available in the U.S., Australia, Canada, Ghana, South Africa, and India, among others.

A few months earlier, Arte es Ética, a collective of Spanish-speaking artists, had issued a manifesto and a petition calling for companies to let people opt into data collection. The group also urged investment firms, production companies, and platforms that use AI to incorporate copyright laws and data protection regulation in their fair-trade rating system, alongside gender equality and carbon footprint reduction.

For now, Brazil offers broader protection to its citizens than elsewhere in Latin America, since its privacy laws are more akin to those in Europe. Meta is legally required to give users in the country an opt-out option. Earlier this month, Brazil’s National Data Protection Authority announced that it would suspend the company’s privacy policy and issue a daily fine of $8,836 in case of noncompliance.

Experts say governments don’t have to draft new AI legislation to shield their citizens’ online content — they can strengthen their data protection laws instead. In Europe, Meta is “facilitating the right to object through the data protection framework, not through the AI Act,” Lucía Camacho, public policy coordinator at the digital rights group Derechos Digitales, told Rest of World, referring to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. “This is purely and simply data protection.”

“Instead of adopting broader protection measures for all… these platforms discriminate based on location.”

Some countries in Latin America, like Bolivia and Paraguay, do not have general data protection laws. Several of those that do, including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, and Costa Rica, haven’t updated them since at least 2012 — though Chile, Peru and Colombia are currently debating new legislation.

Chile is considering the creation of a Personal Data Protection Agency. “Digital platforms wishing to use personal data to train generative AI models will need to obtain specific consent to do so,” Felipe Osorio, public policy advisor at Wikimedia Chile, told Rest of World.

Instagram/@onedoodleperday

For now, users in Latin America feel vulnerable to Meta’s whims. “The fact that our region doesn’t have common priorities in terms of data protection is a challenge,” said Camacho. “The end result is what’s happening now: jurisdictional gaps.”

Artists in the region are worried that AI models, fed with high-quality material they had originally created, are essentially replacing them. Many feel powerless and depleted.

“I’m done worrying about this. I feel that there’s no way to protect ourselves,” Luque said.

She’s not alone. Andrea Galecia, a Peruvian illustrator, began building her creative portfolio in 2007. For Meta to copy 17 years’ worth of dedication to perfecting her technique is “really frustrating,” she told Rest of World. Galecia estimated that about 60% of her income comes from promoting her work on social media.

Some illustrators have left Instagram in favor of Cara, an artist-run social platform, in recent weeks. But for many, abandoning the former isn’t a viable option.

“Many of our clients are not on Cara,” Gaby Romero, an illustrator from Ecuador, told Rest of World. “For small or emerging artists, navigating Instagram’s world is already complex. You can’t ask your clients to migrate to another platform with you.”