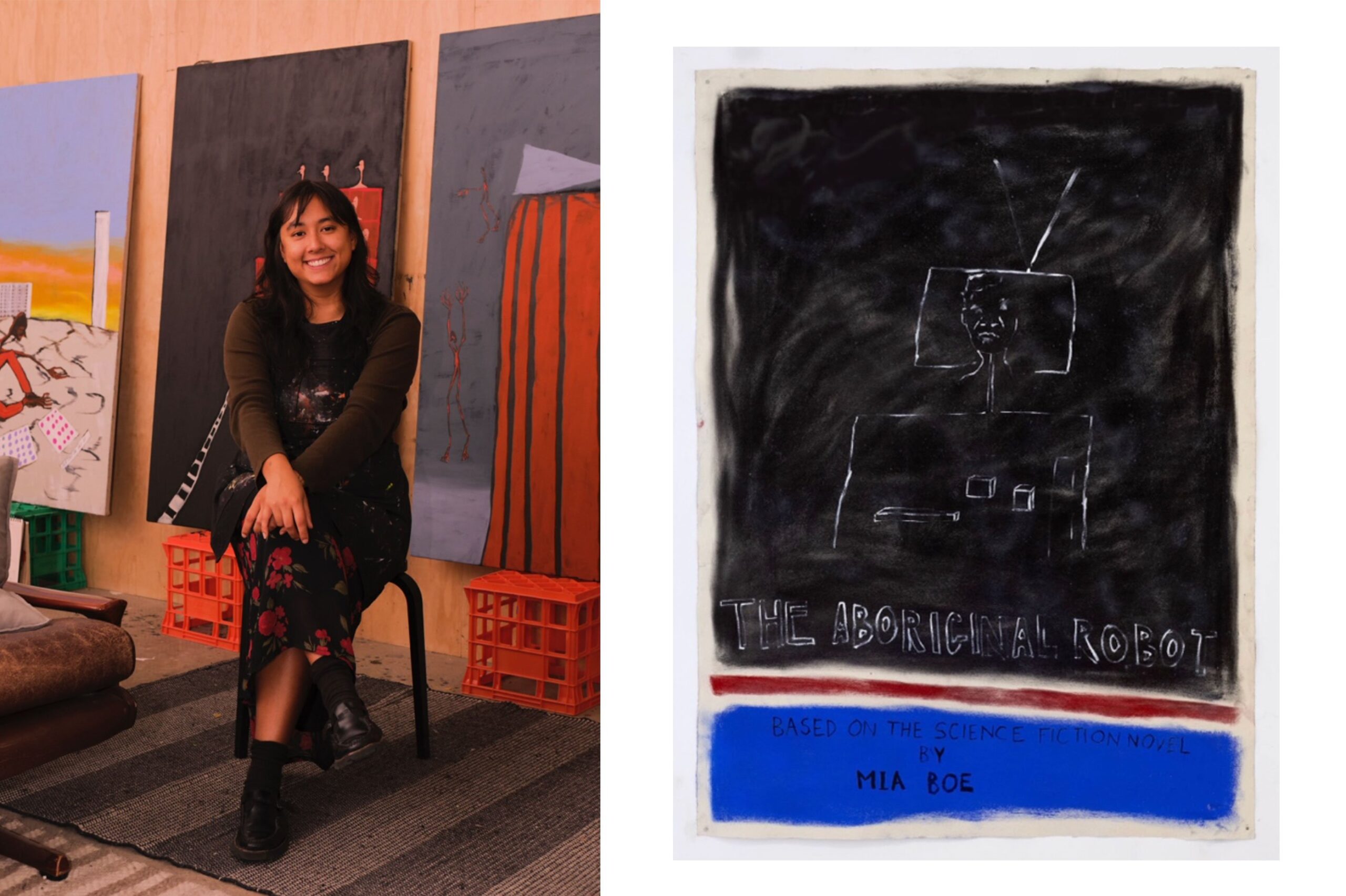

Melbourne-based Butchulla and Burmese painter Mia Boe has had a big couple of years. This year she was a first time Archibald Prize finalist for her portrait of Tony Armstrong, her work has hung at the NGV, National Portrait Gallery, and Monash University Art Museum. She’s been selected as one of the Ace Hotel’s artists in residence, and completed a residency in Mexico City. It’s a lot for a self-taught, or, as she describes herself a “baby artist” (she is also humble and self deprecating), who has only been painting full time for four years. It’s another accolade that her solo show, The Aboriginal Robot, has just opened at Paddington’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery. RUSSH caught up with Boe on the eve of her opening.

Your new show, The Aboriginal Robot follows a narrative arc, and feels a lot like a film’s storyboard. What story is the work telling?

It’s set in this dystopian, not so distant future. Some people have had to leave the planet because the land is almost dark and beyond repair. And so the government creates an Aboriginal robot, an AI system, with Aboriginal land caretaking knowledge. And it’s called the Dreaming Machine. It learns about the people that have exploited the land and profited of the land and of the governments who encouraged those people. And then the Dream Machine begins a revolution. So taking inspiration from Blade Runner, Wall-E even, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and also a little bit from Frankenstein in the creation of this being who turns on its maker.

What were some other influences?

I’ve been reading lots of science fiction in the past year, especially Octavia Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve read some classics recently, like H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, and 1984. A lot of dystopian political science fiction. There’s a great quote by Ursula K. Le Guin, “Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive”. I took that to mean that good science fiction, even though it’s talking about these imagined futures, is really reflecting the now. And so I wanted to make a science fiction story to talk about the state of Australia and the ignoring of the Aboriginal voice and knowledge.

How is this show different from work you’ve done in the past?

I found this show quite difficult to do because I haven’t worked with these imagined stories before. In my past exhibitions I was referencing specific histories or people or stories, I love people’s stories. The works are layered with mistakes, which I quite like the look of. You can see layers behind different colors. In a way I feel quite self conscious because the story is all coming from me rather than relying on history.

You’re self taught. How did you teach yourself to paint?

I just did it. I studied art history at university which showed me which artists I liked, and which artists I didn’t like. And what political artists in Europe and Australia did, which is what I wanted to do, in a way. But really just trial and error.

You did a two-year residency at Melbourne’s Gertrude. How formative was that to your development as a painter?

It was amazing. Because I didn’t do art school, it was the first time I felt like I had an artist cohort that I could ask for advice and share things with, and they would share things with me. It was very social, and the staff are so helpful. I could not recommend it enough to all artists to apply. But like all schools or social situations, it’s good to break out and see that I can exist without relying on everyone there for advice.

Was art important to your family when you were growing up in Brisbane?

My Dad and Mum took me to a lot of exhibitions. The ones I remember were at Milani Gallery, a commercial gallery that represents a lot of very important Australian artists like Richard Bell, Vernon Ah Kee, Gordon Bennett, and Judy Watson. My parents are both lawyers and that idea of seeing things from all perspectives and experiences has helped my thinking in terms of trying to create stories and making art.

Did you consider studying law?

I did, and I actually applied last year. But I don’t know if I want to be a lawyer. I want to learn about the world in that way – the legal system, the justice system. I want to find a way where I can combine art making with that sort of research and understanding. Over the past four years my Dad’s been working on the death-in-custody case of Kumanjayi Walker. I went to Alice Springs twice to watch parts of the coronial inquest into his death.

What’s it like to have your first show with Roslyn Oxley9, the grande dame of the Australian art world?

I was really shocked when they reached out last year, because I feel like such a baby artist, and the artists that have shown here are some of my favorite artists. Tracey Moffatt is my top artist ever. It’s a great opportunity for me.

You are literally following Tracey Moffatt, her exhibition, The Burning, has just come down as yours is going up.

I know, it’s not lost on me… During my art history degree I never would have imagined that.

So, what’s next?

I’ve got a big break from December to November. I’m really scared but also excited. I haven’t had time to experiment all that much and I have a desire to move away from doing only paintings and experimenting with soft sculpture. I’ve been working with a lot of Burmese longyis (sarongs), and embroidery and trying to stitch together objects. I love painting, but I’m excited to do something more tactile with my hands too.