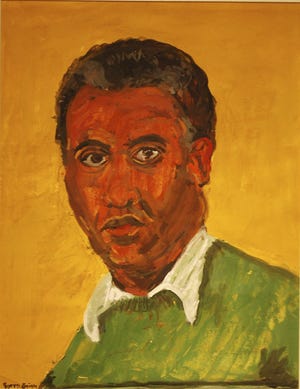

I can’t say, with any confidence, when I first encountered the paintings of Byron Smith.

Upon moving to Columbia almost 17 years ago, his art would become part of the atmosphere; more reliable and unchanging than the Missouri weather, but just as present and deeply felt.

When you so clearly associate an artist with presence, their eventual absence carves a greater void. News of Smith’s death came down this week, conveyed to me through a series of heartfelt social media posts from Smith’s friends and peers in the Columbia art scene.

Just two short months ago, I wrote about his participation in the Persimmon Creek Writers and Artists Residency, an Arrow Rock-based venture that offers artists rest and needed creative resources of time and space while deepening an understanding of the village’s Black history.

At the time, I couldn’t think of an artist better suited than Smith. I still can’t, even as this loss looms large. Smith was as Missouri as they come.

Need a break? Play the USA TODAY Daily Crossword Puzzle.

As the Tribune’s archives recalled to me, he studied art at the University of Missouri with the legendary likes of Frank Stack, who later became a peer and studio mate. Writing about an exhibit at Central Methodist University in Fayette, Cathy Throgmorton described Smith’s clear affection for “the landscapes of the Missouri River Valley and features of the communities that snuggle up to the rivers, especially Rocheport, Boonville and McBaine.”

Across the decades, Smith’s paintings would be exhibited nearly everywhere imaginable in Columbia and around the region, both becoming ambient and offering a distinct immersion with every viewing.

And truly, Smith’s work showed us the best of Missouri, as it is and could be. His paintings, lush and pastoral as they were, never traded in some notion of the ideal. Rather, their deep greens and endless blues offered a right-size, realistic view of our land and of us as its inhabitants.

I cannot separate my experience of living in the middle of Missouri from my experience of Smith’s artwork. Coming from Arizona — where you can experience sun-laced desert and tall, cool pine forests within the same three- or four-hour drive — initially Missouri looked the same everywhere. Smith’s way of seeing the world was as important as anyone’s in redefining, or properly defining, our state’s wild and remarkable personality, and of teaching me to see the beauty beyond Columbia’s city limits.

Today, it seems our state too often falls prey to Mary Oliver’s ever-relevant diagnosis of a politics and a collective heart that’s “small, and hard, and full of meanness.” The presence of artists like Smith provides a contrast and a salve. His work steadfastly showed us — showed me — how the body might be nourished by Missouri’s rivers and how the soul might grow tall in sight of the trees just beyond their banks.

He also gave us small-town scenes, humble portraits of places where the neighbors aren’t perfect but regularly trade kindnesses across the property line. To gaze upon one of Smith’s paintings was to believe, with him, in the goodness of being here and in the ways such good could turn toward fullness.

Smith revealed the best of Missouri in his very manner. Each tribute I read this week invoked his gentleness and generosity, without exception. He was as loud as his paintings, which is to say, a lovely murmur of a man.

There is something remarkable about associating an artist with one place to such a degree that you cannot separate the place from their memory. When I look upon the Missouri landscape, I see a Byron Smith painting; when I see a Byron Smith painting, I see the Missouri landscape. I think this is how it should be.

As I step away from our newsroom a little sadder, I can’t help but project this vision onto the world outside my reach. I see Missouri as a place and a people, each trying to live up to the promise of one another. A now-departed painter granted us glimpses of what this unity might look like.

For this, I am grateful to have lived in Columbia at the same time as Byron Smith. And I’ll rarely be anywhere without his work.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. He’s on Twitter/X @aarikdanielsen.