Throughout March, we have celebrated Women’s History Month with an installation of some outstanding works from the museum’s collection by women artists working in the mid- to late-20th century.

Building on a long legacy of collecting and exhibiting art by women, we are pleased to feature a group of prints by Alice Neel (1900–1984), Faith Ringgold (b. 1930), Grace Hartigan (1922–2008) and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), all of whom overcame significant challenges in their lives and careers.

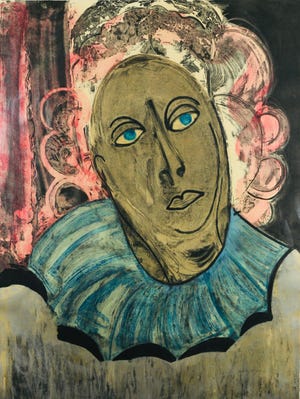

Powerful portraits reflect emotional gamut

Upon entering the museum, you will see Neel’s arresting portrait of her granddaughter, “Olivia.” Visitors have remarked that Neel has brilliantly captured the look of a typical teenage girl, with body language and attitude that suggests the comfortable relationship of a friend who would “flop down and talk.”

Neel, about 80 at the time she made this portrait, surely acutely understood the changes in the lives of young women over her lifetime and powerfully captured a sense of potential and expectation in Olivia’s frank gaze and parted lips.

Neel built her career on unflinchingly honest and intense portraits of family, friends and fellow artists. Her subjects express universal human emotions of fear, strength, pain and defiance, revealing personalities and insecurities. Despite suffering a nervous breakdown, attempting suicide and being hospitalized earlier in her life, Neel nevertheless became one of the 20th century’s most powerful portrait painters. Some longtime local residents might recall a retrospective of Neel’s work at the museum in 1977.

‘Mama can Sing’ and ‘Papa can Blow’

Nearby, you will see two very different prints by Black artist Ringgold: “Mama can Sing” and “Papa can Blow.” A painter, writer, mixed media sculptor, performance artist and activist, Ringgold (now 93!) creates works that comment on themes of race and gender and their relationship to the art world, history, politics and society.

In this pair of colorful prints, Ringgold portrays a jovial pair performing energetic music (most likely jazz or blues). She contrasts light blue and gold motifs and establishes a coloristic relationship between the saxophone’s shiny brass plating and the lyrics that surround each figure.

Ringgold became one of the first artists recognized for making fine art objects from textiles, sewn fabric, weaving, quilting and embroidery, media formerly referred to as “women’s work” and “craft.” During the 1970s, she challenged these stereotypes and succeeded in elevating her textile- and fabric-based work to the level of fine art.

Color sets the tone

Like Neel and Ringgold, Hartigan was intrigued by the human figure. Part of the series “Great Queens and Empresses, Elizabeth Etched” depicts Queen Elizabeth II. By employing contrasts of red and brown, Hartigan created the effect of sunlight shining on Elizabeth’s hair and filtering through the curtain in the background.

Hartigan was one of a small number of women associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement that blossomed in New York City from the late 1940s to early 1950s.

An associate of artists Jackson Pollock, Frankenthaler, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Larry Rivers and the poet Frank O’Hara, Hartigan played an essential role in the artistic and literary awakening that repositioned New York as the center of the modern art world.

Relocating to Baltimore in the 1960s, Hartigan became director of the Hoffberger Graduate School of Painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art. This print reflects Hartigan’s interest in strong women, a choice that paralleled challenges in her own life, including her struggle with alcoholism in the early 1980s, attempted suicide and her husband’s mental and physical decline.

Also nearby is Frankenthaler’s colorful lithograph, “Barcelona,” one of several Frankenthaler created from nine colors in a workshop at the Ediciones Poligrafa, SA in Barcelona, Spain.

In this print, a field of richly layered colors (shades of green contrasted with blue, red and yellow) seem to compete for prominence. At the same time, vertical strokes in primary colors stabilize the composition’s dominant, earthy greens. She uses color and gesture to suggest the evening bustle of the city. Here, the artist created a print that conveys the spontaneity of her paintings and achieves a similar transparency and brilliancy of color.

Influenced by Pollock, Frankenthaler encouraged paint or ink to go where it would when she applied it to unprimed canvases or the matrices for her prints. The resulting works referenced the natural world, posed against and within airy, seemingly fluid spaces; not unlike those found in “Barcelona.”

Often referred to as a color field artist, Frankenthaler was fascinated by the possibilities of sheer color and its unpredictable relationships, inspiring artists such as Kenneth Noland, Sam Gilliam and Morris Louis to follow her lead.

The work by these artists will remain on view through August. And make sure to look for works by other women artists throughout the museum — including Louise Nevelson, Sarah Miriam Peale,and Anna Hyatt Huntington — all responsible for iconic works in the collection.

And while you’re at it, take a look at, and think about, the way women are represented by male artists in the collection.

Art is more than decor: It’s about coming together, preserving traditions, making memories

Daniel Fulco, Ph.D., is the Agnita M. Stine Schreiber Curator at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts. The museum is open Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Sunday, 1 to 5 p.m., closed Mondays and most holidays, including Christmas, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Go to www.wcmfa.org or call 301-739-5727. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and LinkedIn.