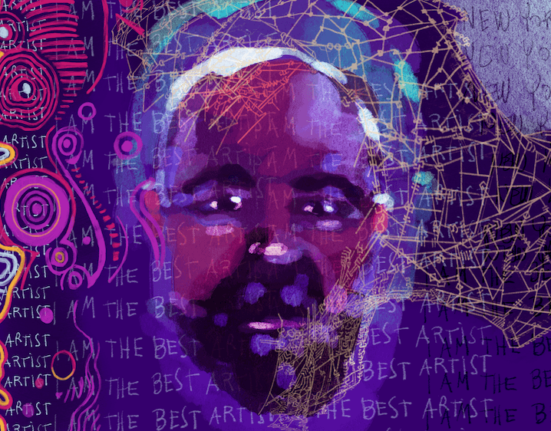

Courtesy Blanton Museum of Art

Artists are commonly thought to toil away in their studios day and night, but that is typically not the reality. In truth, artists need money to fund studio space and materials. For many, making ends meet is not possible through selling art, and this means finding a job.

There is an entire history of artists working at the Museum of Modern Art alone. In the 1960s, sculptor Sol Lewitt worked there as a receptionist, Minimalist Dan Flavin took a job as an elevator operator, and painter Robert Ryman manned the galleries as a security guard. The artist Howardena Pindell even worked as a curatorial assistant in the drawings department; she came up with the idea to use discarded paper punches in her abstract paintings from her time in that office.

This fringe history of artists moonlighting as MoMA workers informed “Day Jobs,” one of the year’s most memorable shows. Held at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, the exhibition was “an attempt to dispel the stubborn myth of the lone genius, working in isolation in the studio creating masterpieces,” as curator Veronica Roberts put it in an interview with ARTnews.

She pointed to Tishan Hsu, an artist now known for painting and sculptures that combine the imagery of technology with the human body. “Hsu was a word processor in the 1980s, and was doing this with predominantly women at a corporate law firm… He began thinking about how screens were changing our relationships with our bodies, and that question has been the foundation to everything he has made since.” A painting from 1982, Portrait, is on view in “Day Jobs”; it depicts glitchy lips and eyes on a panel with rounded corners reminiscent of early IBM computing screens.

“Day Jobs,” with its assertion that artists’ art is not the only aspect of their life which defines them, and indeed that such circumstances impact what they make, was emblematic of a larger trend that could be seen in US museums in 2023. This year, many institutions began to focus on how constellations of artists form around shared lived experiences. Artists were being celebrated as multihyphenates who are influenced by their peers.

This framing lends itself to explorations of artists’ biographies, which have not always been celebrated in the field of curating. Roberts told ARTnews that while coming up as a curator, mentioning an artist’s biography was disparaged. “There was an endeavor to keep an artist’s life totally separate from their work,” she explained. Of course, there are dangers in overusing biography, which can result in flattened readings of complex works and practices, especially ones by artists from marginalized groups. Now, however, it feels like a misstep to not thoughtfully pay mind to the circumstances of art-making, and this is encouraged in shows that expand the very concept of what it means to be an artist.

Installation view of “Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969,” 2023, at Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Photo Olympia Shannon, 2023

One such show was “Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969,” which opened at the CCS Hessel Museum of Art in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, in June. The exhibition considered Native North American artists who had incorporated theatre and performance into their work, and took its inspiration from the 1969 proposal Indian Theatre: An Artistic Experiment in Process, written by teachers at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe. The document proposed that centuries-old forms of Native performance could be reinterpreted for a new age, while also noting that all this contemporary practice “cannot be developed overnight.” In the authors’ words, “it will come only as the result of an educational process in which Indian artists are created who can then make their own statements.”

“The document was a revelation to me as it felt like a missing piece of art history,” curator Candice Hopkins said in an interview. “Here were the dual origins of Native theatre and performance art, rooted in practices of experimentalism and cultural difference.”

By rooting her show in what could be labeled experimental theatre, Hopkins was arguing that the artists she included were inspired not just by art history but by the other arts, too. And she suggested that though they were bound by Indigeneity, these artists were also borne from varying experiences, interests, interpretations, and Native nation affiliations that impacted their art. The show included black-and-white videos of IAIA students performing in masks and regalia, but it also included paintings by Kay WalkingStick, a sculpture by Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill, and newly commissioned choreography by Jeffrey Gibson. All of these artists were “making their own statements,” as the IAIA teachers might have put it.

Installation view of “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines,” 2023, at Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Courtesy Brooklyn Museum

Hopkins’s rediscovery of the 1969 manifesto and archives is a testament to how the IAIA students were creating works not meant for art institutions. The contents of “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines,” a show at the Brooklyn Museum through March 2024, function in a similar way. The exhibition highlights zines (short for fanzines), made in the advent of accessible photocopy machines, from the 1970s to present day.

More than 1,000 objects are packed into the galleries, which present how zines aided in the formation of networks of avant-garde musicians and visual artists, many of whom were queer. And many wear multiple hats. Vaginal Davis, for example, appears in this show as an artist, a model, and a musician. She was credited in over a dozen wall labels, for her self-published Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine (1987–91), for being a subject in Rick Castro’s photographs, and for her collaboration with Lawrence Elbert on the music video The White to be Angry (1999), produced to accompany a song by her punk band Petro, Mureil and Esther (PME). Davis even tracked the interconnectedness of the North American punk scene in the “History of Punk Timeline” (n.d.)—a foldout made for the Toronto-based J.D.s magazine (1985–91).

Branden W. Joseph, an art historian who curated the show with Drew Sawyer, said of the exhibition, “These relationships were not only on the basis of actual lived experience, but also, in many cases, fostered by relationships and situations that artists imagined and then brought into existence for themselves.” The zine, which can be printed matter in addition to video and audio cassettes, was an extension of mail art and artist books, and came into being to meet these community-building desires. And while the exhibition tracks the zine’s genesis in a pre-internet era, it also argues for its enduring popularity with a space devoted to contemporary practitioners.

In a much different way, this year’s edition of the Made in L.A. biennial, titled “Acts of Living” and now on view at the Hammer, mirrors the curatorial thrust of “Copy Machine Manifesto” with stated ambitions to “situate art as an expanded field of culture that is entangled with everyday life,” according to its description. The show includes an exhibition-within-an-exhibition by the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA), which has installed a break room (including a Bunn coffee maker, microwave, and soft Muzak) to house a selection from its collections. Food, drink, and casual browsing is unheard of in archives, and LACA wanted to create an alternative space for this.

“It’s very much a conversation on preciousness and preservation” LACA’s director and archivist Hailey Loman told ARTnews. “We emphasize that we want you to work in this space, we want you to hang out here … We are not interested in preserving materials ‘forever.’ We care about how looking at a document can make changes to our lives right now.”

The Los Angeles Contemporary Archive’s installation in Made in L.A.

Photo Joshua White

The collections include paper trails from the practices of Patricia Fernández, Barbara Kruger, and others. And while Loman described that archives often prioritize press releases and documentation of exhibitions or performances, those that pertain to the nitty-gritty of process receive a subsidiary focus. In LACA’s collections, there are gas bills, studio leases, even paintings that were deemed subpar by the artists and then tossed out. “These are things that help us to learn how art is getting made and how people are living and surviving,” Loman said.

This greater acknowledgement of the labor involved in the arts coincides with a burgeoning workers’ movement in museums. Across the country, staff at institutions ranging from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to the Buffalo AKG Art Museum have led unionization campaigns. Meanwhile, artists are agitating for fair compensation. In 2018, the W.A.G.E. organization released their often-cited fee calculator, which determines project-based payment by both an artist’s participation (i.e. solo or group show) and a nonprofit’s annual operating expenses (i.e., from Apexart to the Met). Institutions can advertise their W.A.G.E certification status if they comply with these rates; the most notable ones to do so have been Artists Space and the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland.

Roberts, the “Day Jobs” curator, said that her show is connected to both developments. At the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, where she is the new director and where the exhibition travels in the spring, “Day Jobs” will become the first group show held at the institution where participants will be paid a fee. Roberts said this not only has to do with the agency that comes with her directorial position, but also the labor and financial precarity that her show makes clear: “That discussion connects to the exhibition itself, and the consideration of artists’ lived experiences and the conditions of making.”

To put it another way, there are many forces outside the studio that affect what happens within. In 2023, reconciling the two became the job not just of artists, but the institutions that exhibit their work, too. That trend looks to continue as “Day Jobs” travels in 2024.