Lynne Tillman Joan, you’ve just come from MoMA. What was it like installing this … are you calling it a retrospective?

Joan Jonas I’d never do that. I’m calling it a survey because it is not everything I’ve made, but it’s a lot.

LT How do you figure out the best way to show all this very diverse work?

JJ You have to make a model, so a model, actually two, were made: one is at my place and the other, which was the working model until very recently, is at MoMA. And then I worked also with the curator, Ana Janevski, who is very good. The MoMA team has been in my loft doing research and going through the archives for almost three years, so they knew the work incredibly well by the time I got to MoMA.

LT How did they make the selection? You have one of the most varied careers, with numerous works across multiple disciplines.

JJ In 1994, I had a show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where I turned a lot of my performances into installations, meaning I rearranged the material and changed the form but kept the same content. In turn, these installations were documented on video. Since then, I’ve been developing some of those works continuously. They get shown over and over again. I know installation is also a general term for arranging things but, for me, it is a form that I work with. And, in the case of this show at MoMA, many of the works have been exhibited already: first at Tate Modern, London, in 2018; then at Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto, in 2019; and, most recently, at Haus der Kunst, Munich, in 2022–23. So, we’ve added some new works to the MoMA show to make it more unique and interesting.

LT And more current?

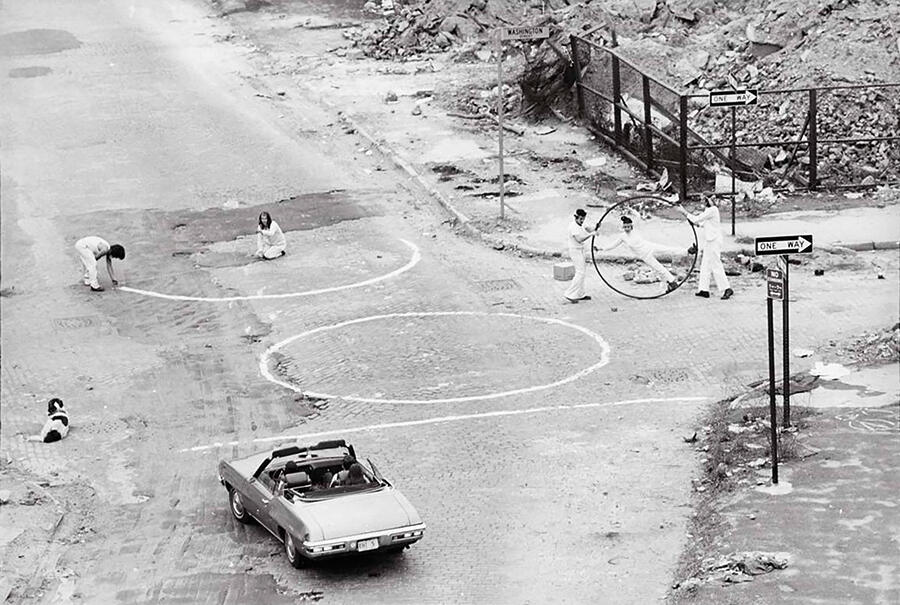

JJ Yes, it’s more current but there’s work from the very beginning, starting in the late 1960s when I began my ‘Mirror Piece’ series, to the present.

LT I like those early works and I usually don’t like mirrors in art.

JJ Oh, really? That’s interesting. I started working with people carrying mirrors in formations for performances towards the end of the 1960s. At the start, I used full-length mirrors, which reflected and changed the space around them. I was initially inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’s short-story collection Labyrinths [1962], in which he mentions mirrors many times. So, I just took all those quotes from Borges and memorized them. My very first performance was reciting Borges while wearing a mirror costume.

LT Around that same time, during the 1960s and ’70s, the Judson Dance Theater also featured women – and men – performing nude or scantily clothed. Specifically, I’m thinking of Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy [1964] and later Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A with Flags [1970/2019]. How did you feel about showing your face and body during these early performances, as well as in video works such as Vertical Roll [1972]?

JJ I wore masks in the beginning. I went to Japan and I was inspired by Noh, the classical dance-drama form, which uses masks to cover the face. So, in my first few performances – though not in the mirror performances – I often wore a mask to transform my persona. I remember I had extreme stage fright in the beginning, which I’ve gotten over now, but I never questioned the use of my body or my face: my body was my vehicle.

I never questioned the use of my body or my face: my body was my vehicle.

LT Do you think because you were a dancer, you imagined your body differently, say, as a vehicle of expression, an object for exhibition?

JJ Well, when I decided to switch to dance, I was studying art history and making sculpture. I had wanted to make a move to performance, and the way I decided to do that was by spending a couple of years going to every dance workshop I could, because I had never performed in front of an audience. So, I made up that gap by working with all these dancers.

LT Was that with Simone Forti?

JJ She was one of them. Yvonne, too.

LT Trisha Brown?

JJ Yes, definitely Trisha, and Deborah Hay. Everybody needed a little money, so they were all doing workshops. But, also, ‘happenings’ were huge in the 1960s. I switched to performance and dance because I was inspired by the happenings of Lucinda Childs, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. That’s what I wanted to do.

LT Was it also that you wanted to be working with people?

JJ Partly, yes, but not entirely. I make a lot of work that doesn’t depend on people, like my drawings and videos. When I first got a video camera in 1970, I spent a lot of time by myself with it, working with the closed-circuit system of early video.

LT You were one of the first people to work with video.

JJ Yes. This is something I say often but, when I switched to performance or live art, I really saw all the forms coming together: writing, drawing, performing, music. For me, it was about different aspects uniting and informing each other in my work.

LT Over the years, you’ve added many other elements.

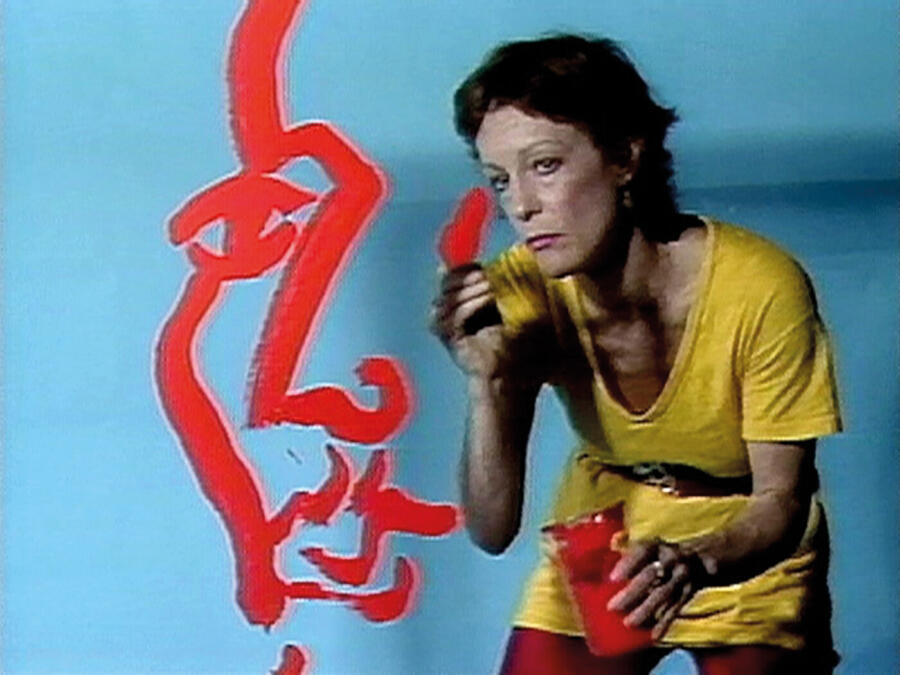

JJ What interested me at first about video was the layering. There was the projected video and the live performance taking place in front of it, which was being filmed and would also, in turn, be projected, so the audience saw several things simultaneously. I wanted to pile meaning into all those layers.

LT You also work with words. I think of you as a literary artist, whether you’re including poetry or prose or using it as the basis to begin a work. You mentioned Borges as an inspiration to use mirrors in your work. I feel your practice has always been undergirded by writing.

JJ I have always loved to read and, even before becoming a performance artist, I was very inspired by James Joyce’s Ulysses [1918–20]: the way he used the myth of Sisyphus to illustrate a novel. That intrigued me and, later, I started bringing into my own work this idea of the myth representing something or someone in the story.

LT I want to talk a little bit about how your work deals with ritual. In contemporary life, there aren’t many rituals we still observe. Is that absence partly why it became important to you?

JJ In the 1960s, when I was looking to make the transition to performance, I heard about the Hopi snake dance, which takes place annually in northern Arizona. I went there to see it and it was amazing. They train the snakes for weeks and weeks beforehand and then the dancers perform with the rattlesnakes in their mouths. Of course, in respect to Indigenous customs, I could never have included that dance as part of my work; it was an inspiration, not a source.

The idea of performing outdoors was also a source for my work. I was reading books about shamanism, and so on, which became the basis of my inspiration. I thought of my early performances in New York as rituals. My rituals, however, would be just simple things that we do every day, like walking. It wasn’t something I said on a megaphone or made a big issue out of, it was just my way of giving myself a platform to stand in the middle of the room and move and make sound.

LT Like giving yourself permission to do that because you are, when you are performing, an icon, representing not yourself but another figure or an idea. The objects that you bring onto the stage are also unexpected, tall paper cones, for instance. But I would say one aspect of your work is a feeling of reverence.

Nature is sacred, the life of animals is sacred, children are sacred. There is reverence for life in your art.

JJ Really? That’s interesting.

LT It’s not religious. We often think of religion and reverence together, but what I believe you’re trying to create is – maybe like the Hopi snake dance you watched – appreciation for the sacred. Nature is sacred, the life of animals is sacred, children are sacred. There is reverence for life in your art.

JJ Maybe you’re right: there is this kind of spirit in the work.

LT Yes, the spirit. When a performance is going on, even if I can’t make total sense of what happens before my eyes, the feeling is that life is precious. A feeling beyond reason.

JJ Exactly. I always tell people to just experience the work. The way I put a piece together is to take, say, a work of literature or a poem as a starting point, but I don’t illustrate it. My work is not illustrational: it’s associative, intuitive. So, of course, it’s a little opaque, I agree. But that’s the way I work.

LT It’s too easy to say it’s dreamlike.

JJ No, no, no! I don’t ever say my work is a dream. Never!

LT No, neither would I, although I can imagine some people do. I’ve made film and included non-narrative, non-linear elements in the work and discovered how much possibility accrues from juxtapositions and elisions. Also, from playing with sequences, you have other, new visual ideas.

I wanted to pile meaning into all those layers.

JJ It’s good you brought up film because it’s one of the many forms I work with – perhaps the main one, I would say. Also, being in New York and living next to Anthology Film Archives, co-founded by Jonas Mekas, was a treat. I went as much as possible and I learned so much from what I saw there, in particular montage and layering techniques – filmic structure.

LT That’s why, when I wrote an essay about your film Berlin Road Movie [1971] in the book Joan Jonas is on Our Mind [2017], I noted that you were using the Kuleshov effect – an editing technique which juxtaposes one image against another. It’s the same in your performances, different elements layer on top of each other, figuratively, juxtaposed, and affect a spectator in ways that can’t be described instantly. I think about the playwright Richard Foreman. His plays are very different from your performances, but he was likewise looking at the irrational. You’ve also mentioned how you were inspired by Maya Deren’s films.

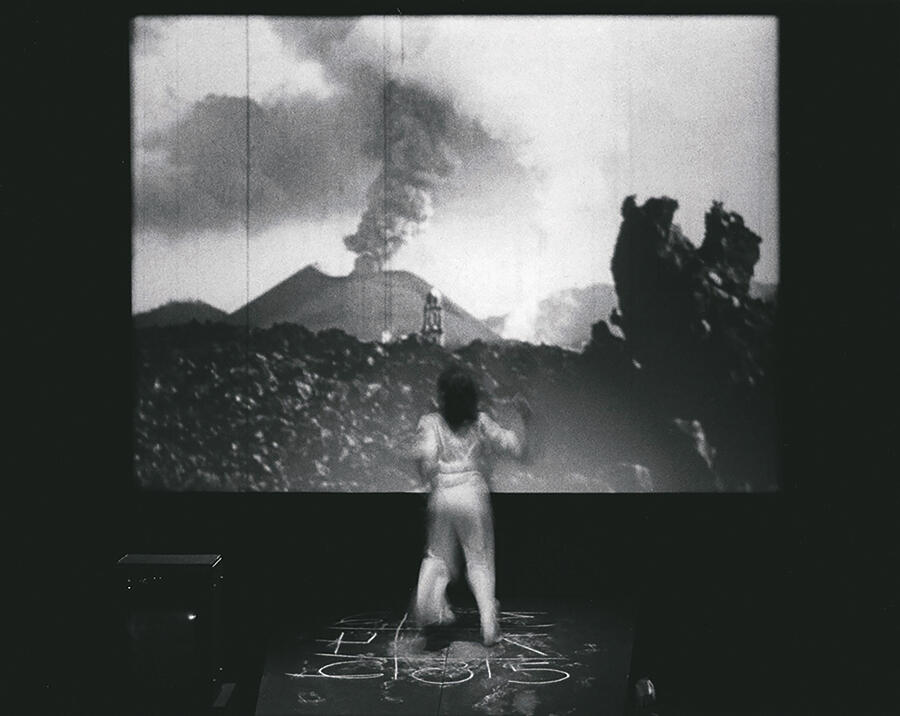

JJ It’s hard to believe, but I didn’t see Deren’s work until after I’d done my ‘Mirror Piece’ performances. She was a brilliant filmmaker, but the main thing that drew me to her was a four-hour screening at Anthology Film Archives in 1976, of all the unedited footage she had shot in Haiti between 1947 and 1954. This had a major impact on me; in particular, it influenced Mirage [1976/2001], which is included in the MoMA show.

I saw Haitians perform these rituals where they would draw symbolic images [vèvè] of Vodou spirits in the ground with white sand. After that, I started drawing with chalk on a blackboard in some of my videos, or on the ground during my performances. Seeing that footage of Deren was inspirational, of course.

LT Can you speak about your performance and installation piece The Juniper Tree [1976/94]?

JJ Do you know the Brothers Grimm story of The Juniper Tree [1812]?

LT I don’t. I know Oscar Wilde’s grotesque fairy tales.

JJ Well, The Juniper Tree is a terrible story about redemption. It starts out with a mother who dies shortly after giving birth and is buried under a juniper tree. She leaves behind her son and her husband. In time, the father remarries and has a daughter with his new wife. The stepmother, however, hates her stepson and, one day, lures him to peer into a large trunk filled with apples and then slams the lid down on the little boy’s head, decapitating him. She cooks the boy in a stew to dispose of his body, while his grieving half-sister gathers his bones and buries them under the same juniper tree as his mother. The little boy’s spirit arises from under the juniper tree in the form of a beautiful bird, who then drops a big millstone on the wicked stepmother’s head, killing her. So, it’s a happy ending.

LT It’s so interesting, the relationship of these kinds of myths to psychoanalysis, because fairy tales, as gruesome as they can be, are often lessons for children and, later, adults to experience their own feelings of aggression.

JJ It’s funny because, when I first showed this work, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, it was as a piece for children [The Juniper Tree (Children’s Version), 1976]. Shortly before the performance started, several mothers came up to me and told me that they had read the story and were horrified that I was performing it to their children. But I had just read Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment [1976], so I told the mothers it was a teaching story: the children learn how to deal with anger, as you say, and it all turns out fine in the end.

LT Albert Einstein famously urged a mother, who wanted her son to be smart, to have him read fairy tales.

JJ I remember Simone and Kiki Smith were performing in the 1976 version. And it was quite funny because everybody was kind of out of it – it was when we were all drinking and smoking – so there would be these long silences here and there. It was kind of chaotic! Then the technician had made a lightbox, but he thought it wasn’t working, so he kept turning the power off, causing everything to stop! Afterwards, the artist Bob Morris came up to me and said: ‘I finally understand your work, Joan!’

This article first appeared in frieze issue 243 with the headline ‘Conversation: Lynne Tillman and Joan Jonas’

Joan Jonas’s ‘Animal, Vegetable, Mineral’ is on view at The Drawing Center, New York until 2 June. Her exhibition ‘Good Night Good Morning’ is on view at MoMA, New York until 16 July

Lynne Tillman’s Thrilled to Death will be published by Soft Skull Press in 2025

Main image: Joan Jonas, Mirror Piece I, 1969, performance view. Courtesy: © Joan Jonas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York