In the brief moments before totality, the palette of the sky deepens to a twilight blue. As the Moon glides in front of the Sun, wispy streaks of white-appearing light radiate outwards, while a halo of fire encircles our swiftly blackening star. There’s a lot of science going on during an eclipse. But scientists are not the only ones preoccupied with these heavenly views; for centuries, artists have stood beside astronomers, with paintbrush or chisel or camera in hand, trying to capture the colors, shapes, and shadows of the moment.

The extraordinary wonder and great dread of an eclipse have served as inspiration for some of history’s most impressive and imperative works of science art. And though artists from many millennia and cultures have used different mediums to capture the feeling of cosmic connection for their own reasons, sometimes they were enlisted by scientists. After all, documentation of celestial events can help astronomers further study the remote happenings of space. Now, NASA is once again turning to art for the solar eclipse on April 8.

Artistic creation hasn’t been far from astronomy since 3340 BC, when the earliest known record of a solar eclipse was created. A 5,364-year-old petroglyph depicting overlapping concentric circles was found etched on a stone megalith in Ireland, inscribed by Neolithic astronomer-priests. The mesoamerican Maya civilization also used rock art to record their startlingly accurate eclipse predictions, and the Pueblo society carved pictographs of a dark sun reaching outward with fiery tangles into New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon during the 1097 eclipse.

Babylonian stargazers were first able to foresee solar eclipses with the discovery of the saros cycle around 7th or 8th century BC, but even this early scientific finding didn’t change the human desire to pair eclipse art with the unknown or mysticism.

Quite a few pieces from Asia depict mythology, such as Chinese book illustrations from the fourth through first centuries BC picturing legendary dragons or menacing dogs and cats devouring a sun, symbolizing the fear that their lifeforce would disappear. Intricate funerary vases sculpted by Chinese artists in the 1300s show the same fabled dragon chasing an eclipse with eager jaws.

In other parts of the continent, many traditional works of Tibetan art honor Rahula, a protective deity who was fueled by consuming bodies of the cosmos, causing the sun to eternally vanish. And in Japan, artists created woodblock paintings, such as a 14th-century woman confronting a wicked ghost below a shielded sun.

Painted eclipses in Europe tended to be associated with religion, since the Christian Bible describes one during the crucifixion of Jesus. Consequently, one famous piece by Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele depicts the scene in the late 1800s with a charcoal-colored sun in the background.

It was in the 20th century that art and science really became as intertwined as the Sun and the Moon. Before photographs could technically capture the exact instance, artists were commissioned to document the essential details of color and light during the moments of totality.

Then in 1918, in cooperation with Princeton’s Astronomy Department, the US Naval Observatory hired famous landscape artist Howard Russell Butler to memorialize one of America’s most extraordinary eclipses, one that would cross the contiguous United States from coast to coast. The science community believed Butler’s shorthand sketching and painting technique were perfectly suited to mimic the transient effects of nature. He cataloged the solar conditions with such astounding brilliance and accuracy, he was called upon repeatedly to record subsequent eclipses—forming an inextricable link between visual artists and scientists.

Art and science seem like disciplines that couldn’t be more disparate, but both fields draw from the powers of observation and interpretation, and both are rooted in the same human drives to explore and innovate. Many in each line of work equally seek the truth. Creativity has a constant and critical role in all scientific breakthroughs, just as art conveys society’s most penetrating and novel understandings through a highly personable lens.

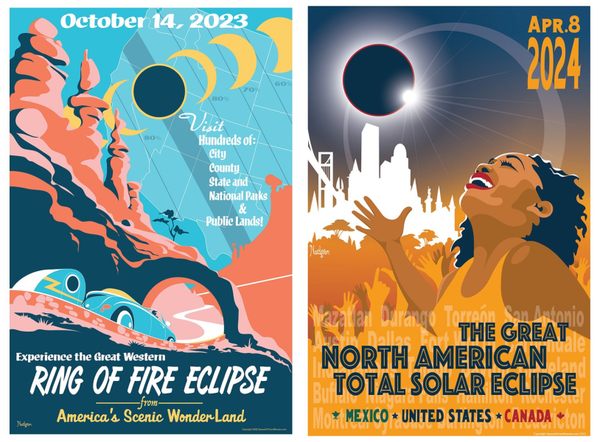

NASA seemed to recognize a connection between the fields. Six years ago, they launched a themed poster project to celebrate and further advance the art-science connection. The posters creatively depict the environments where people live within the paths of totality. Now, to honor what NASA astronomers are calling “The Heliophysics Big Year” (a global celebration of the different ways the Sun touches people on Earth), the project is showcasing artists who aim to design works that not only offer safety and factual information, but also use imaginative graphics.

“This is also about inclusivity. The posters were made by a diverse group of contributors from different races, backgrounds, and life experiences,” says Denise Hill with NASA’s heliophysics outreach team. “We want everyone to connect and see themselves in this art project.”

The 2017 solar eclipse traveled above multiple U.S. national and state parks and across America’s agricultural heartland. As it approached, NASA invited dark matter astronomer and eclipse-chasing artist Tyler Nordgren to create original scientific yet eye-popping posters that educate, engage, and foster astro-tourism in these remote locations.

It wasn’t until Nordgren attended a professional astronomy conference in Hungary that he would witness his first total solar eclipse. He was instantly struck with exhilaration and marvel. “I knew exactly what I was going to be looking at, yet my hair stood up on my neck, and in that moment, I understood the difference between knowing and feeling,” he says. “It’s a multi-sensory experience that evokes a deep emotional response.”

Nordgren’s unique artistic style resonates with that sentiment. It’s a mesmerizing blend of must-have communication and dreamy nostalgia drawn in an array of muted nebula tones. His work so expertly highlights the iconic landscapes of eclipse regions that it has been adopted by the Smithsonian. Since the NASA project’s inception, he has prolifically produced around 85 pieces of striking poster art to promote public eclipse observation.

The art project extends through December 24 this year, but NASA intends to continue their art and science connection through various recurring collections. After April’s eclipse event, they will host an exhibit where the public can imaginatively share their eclipse experiences through social media. Hill adds, “It is a way for us to see beauty and connect to our universe creatively.”

The art brings a human perspective to the eclipse. As Nordgren explains, “An eclipse is not the alignment of the Sun, the Moon, and the Earth in the universe. It’s the alignment in the universe of the Sun, the Moon, and you—the observer—at a rare moment in time.”