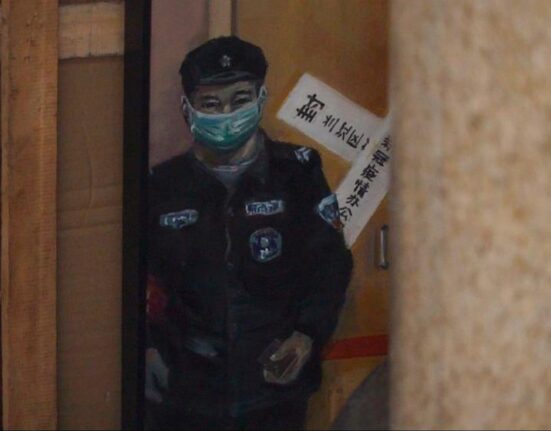

“Nordic Utopia?” installation view at National Nordic Museum in Seattle.

Of course they went in part to escape the horrific racial violence and pervasive inequality in America, the Black artists who looked to the Nordic countries as a creative safe haven in the 20th century, but there was more to it than that.

“(In the 1930s), musicians (and) singers are touring through the Nordic countries–Fats Waller commented on their appreciation for swing music, but also a deep understanding of it–so there was an audience for performing artists,” Leslie Anne Anderson, Chief Curator of the National Nordic Museum in Seattle, told Forbes.com. “For visual artists like William H. Johnson, he traveled of course to Paris, where he met his wife who was a Danish artist herself, and then relocated to the Nordics.”

The National Nordic Museum examines the captivating stories of African American visual and performing artists who found refuge and creative freedom in the Nordic countries beginning in the 30s during a first of its kind exhibition, “Nordic Utopia? African Americans in the 20th Century,” on view through July 21, 2024.

Anderson had been thinking about William H. Johnson (1901-1970) when Ethelene Whitmire, Chair and a professor in the Department of African American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, spoke at the National Nordic Museum in 2019. The pair of museum professionals had much in common. Both were past American-Scandinavian Foundation Fellows, both Fulbright Fellows, both spent time at the University of Copenhagen.

Whitmire’s talk centered on African Americans in Denmark. Afterward, the two discussed collaborating on the topic, perhaps focusing on Johnson, a painter finally receiving his due with a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and a spotlight shining on him during the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.” The pandemic interrupted their conversations, but in 2021, Anderson reconnected to propose collaborating on a pan-Nordic exhibition covering a broader scope of Black artists across numerous creative fields.

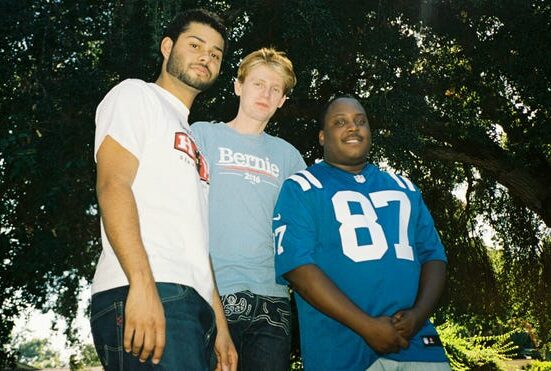

From the soulful melodies of jazz legend Dexter Gordon (1923-1990) to the bold expressions of multimedia artist Howard Smith (1928-2021), and the captivating movements of choreographer Doug Crutchfield (1938-1989), “Nordic Utopia?” illuminates how these pioneering individuals discovered a unique environment ripe for innovation and artistic exploration in the Nordic region.

Their expeditions were largely centered in the Nordic capitals: Copenhagen in Denmark, Helsinki in Finland, Stockholm in Sweden, and Oslo in Norway.

“They found a place where they could release their creativity, they could pursue opportunities that they may not have had in the States,” Anderson said. “We were very deliberate with the question mark (in the title) because there’s no such thing as a utopia, but (the artists) for the most part talked about how their experiences–professional and personal–were improved in the Nordic countries.”

The 1930s were peak Jim Crow. Decades before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 even attempted to make public life and employment equal for the races, a promise yet unfulfilled in America.

In addition to the physical violence and state sponsored humiliation and inequality, racial prejudice hung on African Americans like a lead blanket, sapping them of their energy to create, their drive to create, the joy of creating.

World War II ended the first wave of African American artists journeying to the Nordics, but they would return.

Take Two

“Nordic Utopia?” installation view at National Nordic Museum in Seattle.

After the War, conditions in America for its Black citizens didn’t meaningfully improve. As was the case following World War I, returning Black soldiers who thought their willingness to fight and die for their nation would hold them in greater esteem in the eyes of their racist countrymen were sorely mistaken.

Howard Smith served eight years in the Army before attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1960. In 1962, he went to Finland.

“Howard Smith experienced a tremendous amount of racism in his artistic education, in his life, that was a major reason for him going into Finland, but he went as part of a CIA backed program that was organized to challenge the perception of American race relations abroad,” Anderson said. “He arrives in Helsinki as part of this group and ends up staying there; what he mentions in interviews is that he feels so much more free to produce creative work abroad without concern of race.”

Smith returned to the States, but ultimately decided to go back to Finland and live out his life there.

Europe remained a haven for Black artists in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, particularly the Nordics, where a burgeoning jazz scene required talent to feed, talent pushed out of America by the advent of rock and roll.

“In the 50s, you have jazz clubs being established–Jazzhus Montmarte was a major spot in Copenhagen for folks like Dexter Gordon,” Anderson explains. “There was the promise of the audience that had already been established, an economic promise of going to the Nordic countries, but there was also a community of music makers, of music enthusiasts, who would really support the arrival of people like Dexter Gordon or Duke Jordan (1922-2006).”

African American musicians begin collaborating with other expats and Nordic locals. Word spreads attracting more likeminded individuals to explore the scene. Jazz label SteepleChase records was founded in Copenhagen in 1972. Duke Jordan became one of its first artists to produce an album. A gallery in “Nordic Utopia?” features Gordon and Slide Hampton’s “A Day in Copenhagen” record playing.

The emerging jazz scene in Copenhagen was mirrored in Stockholm during the 60s and into the 70s. At the same time, a group of visual artists decided to go to the Nordics as opposed to Paris because of this burgeoning community. Anderson credits John Hays Whitney fellowships with allowing many of these artists to continue their studies abroad.

“Clifford Jackson (1927-2006) goes to Copenhagen and Stockholm, he ends up living the rest of his life in Stockholm,” Anderson said. “He knew other visual artists in New York like Sam Middleton, who also had a Whitney fellowship. (Middleton) ends up going to Stockholm and Copenhagen for a short period–a year –and then he goes to the Netherlands and remains in the Netherlands.”

While clubs and record labels welcoming the African American musicians, the painters, likewise, found galleries and collectors in the Nordics less burdened by racial considerations than their American counterparts.

Jazz music, abstract painting, creative freedom, community, equality, economic opportunity.

“The arts are influencing each other and visual artists are hanging out with performing artists,” Anderson said. “Sam Middleton (1927-2015) and Clifford Jackson knew Miles Davis and Dexter Gordon in New York and they reconnected with Dexter Gordon and others in Copenhagen and Stockholm.”

As the 60s advanced into the 70s and international commercial air travel became more commonplace, another major barrier discouraging African American artists from sampling the Nordics was lessened: homesickness.

Visiting ‘Nordic Utopia?’

“Nordic Utopia?” installation view at National Nordic Museum in Seattle.

Through artifacts, music, paintings, drawings, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, photography, film, and journalistic writings, “Nordic Utopia?” offers a comprehensive exploration of how individuals found creative freedom in these predominantly white countries.

Highlights include masterpieces by William H. Johnson from the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Gallery in Washington, DC. Intimate glimpses into the personal collections of artists like Ronald Burns and Howard Smith have been generously shared by their families for display.

Following the exhibition’s run in Seattle, it will travel to the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, WI, and Scandinavia House in New York City.