“When you can’t think of what to draw, draw a head,” the Brooklyn-based artist Nicole Eisenman has been known to say, per a catalog for her critically acclaimed traveling retrospective currently on view at the MCA Chicago. “Shape Driven Heads,” a new series of paintings, hangs in her recently opened solo show at Hauser & Wirth in Paris, linking the artist’s well-known, figurative paintings and sculptural practice.

Texturally rich and colorful, the edited, curvy architectural portraits on view are similar to “how a child builds a tower out of blocks, putting these things together, and taking away shapes,” Eisenmann said in a recent conversation as she was opening her Paris exhibition. “It’s a building process.” They also share plastic to-go-cup lids as eyes.

“Sometimes I need a break from constructing stories and [to] just paint,” she said of her minimal, new head paintings. “There’s still a story, just way simpler, and less important. It’s where the paint leads you as you go along, you’re both making the painting and discovering it at the same time.”

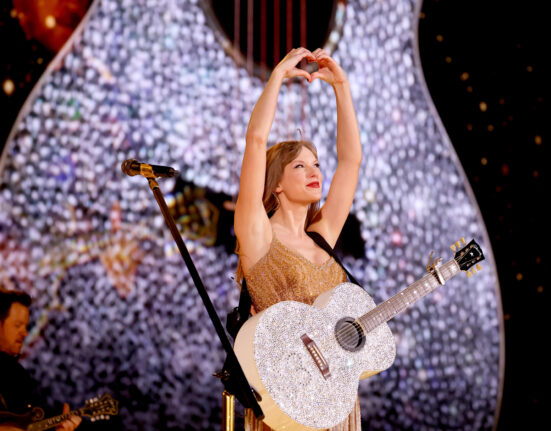

Nicole Eisenman The Artist at Work 2023. © Nicole Eisenman. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Born in France in 1965 and raised in Scarsdale, New York, Eisenman is one of the most well-respected painters; with a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Foundation Fellowship under her belt and global institutional recognition worldwide, including participation in the 2019 Venice and Whitney Biennials, she is by now a veritable art star.

Yet Eisenman has never claimed any of it was easy, whether in terms of her art career, which she felt experienced a dip in the early 2000s, or in her need to momentarily escape parts of her practice and explore others in a wide breadth of media. Eisenman touched on this as we walked through her exhibition at Hauser & Wirth, “Nicole Eisenman. with, and, of, on Sculpture,” on view until September 21.

On display here is bifurcated painting and sculpture practices that ricochet off of each other. The Brooklyn-based artist’s depictions of contemporary human experience, which range from the suppressed to the overt and include incisive socio-political commentary, are still ever-present. Deeply engaged with the tumultuousness of our modern life, Eisenman processes it from her own, gender-fluid perspective, and conjures the results in weighty, textural stories that go beyond verbal comprehension, hitting with full-body force.

Transformations and Narratives

Once a trompe l’oeil painter by day, decorating interiors in New York, Eisenman has gone from graphic, figurative painting about lesbian life in the 1990s to a looser expressionist painting breakthrough in the mid-2000s, which carried over into sculpture and abstracted forms. Her inclination to step back and forth in a kind of dance, in and out of narrative-focused works is understandable. When seeing her own retrospective, the artist said she was struck by the sheer quantity of figurative works.

“I’ve told a lot of stories,” she noted, comparing the process in some of those allegorical paintings to a writer’s cerebral “plotting of a novel.” In contrast, she says that sculpting is about “mashing, binding, splicing, smoothing, conjoining” of shapes.

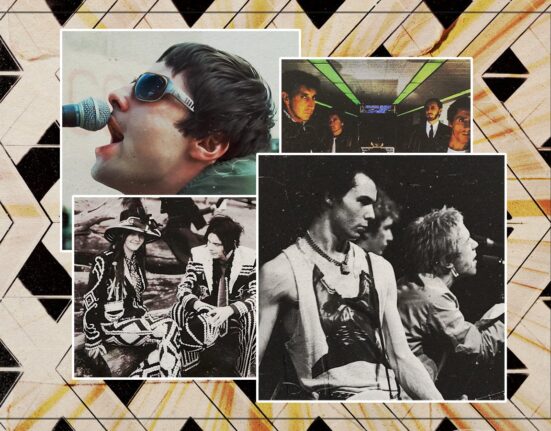

Installation view of “Nicole Eisenman: What Happened” at Whitechapel Gallery in London closing January 14, 2024. Photo: Damian Griffiths, courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery.

The Pig in the Room

Her detailed and densely populated depictions of gatherings are sometimes compared to Auguste Renoir’s paintings of 19th-century revellers, which is one of her inspirations in addition to James Ensor’s expressionist groupings of masked, idiosyncratic figures. Echoes of Pieter Bruegel and Edouard Manet, combined with the cartoonish-ness of Philip Guston, can sometimes be detected in her work.

But despite pauses, Eisenman’s narrative plotting remains an integral part of her recent projects. Central to the exhibition in Paris is a new, large painting titled Archangel (The Visitors) (2024). It depicts an art gallery full of people mostly milling among modernist sculptures (one grabs the wallet out of an elderly man’s pocket). Looming above them is a massive, pig-headed figure dressed in a green soldier’s uniform from World War I.

The figure’s black leather boot is pressing on the head of one unsuspecting person in the back, but nobody in the painting appears to realise that a monstrous creature is breathing down on them. At the painting’s focal point, coming into the gallery from the back, are men Eisenman rendered from photographs of Joseph Goebbel’s 1937 visit to the Nazi-dubbed “Degenerate Art” show.

Nicole Eisenman Archangel (The Visitors) 2024. Photo: Thomas Barratt, © Nicole Eisenman. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The pig-faced soldier is a reference to a Dada sculpture by John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter, called Prussian Archangel (1920) that was once installed hanging from the ceiling; the piece has stuck with Eisenman since first seeing it in a book some 30 years ago. “I thought it was just the ugliest, creepiest, weirdest sculpture, and I’m still fascinated with it,” she said.

Recently, the work began making much more sense to the artist. “It is what is hanging over us. All of this,” she said of the painting. “It’s something that’s in the room, that nobody is paying attention to … but what hangs over us is really terrifying. It’s ghastly.”

“It could be fascism, war, genocide, or the specter of a kind of repression, and it can come from unexpected places,” she added. Without wanting to get into specifics, Eisenman allowed that she is in part referring to current forms of censorship in culture and elsewhere, and the way they “land like an anvil, and self-censorship slips in sideways.”

Eisenman’s Jewish family fled the Nazis, leaving Vienna, Austria, in the 1930s; the artist has made work addressing this trauma and loss. “It’s part of my job as a human on earth to process the sadness of my family,” she said in an interview quoted in her retrospective catalog.

Nicole Eisenman, Fishing (2000). Photo: Bryan Conley, courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art.

Along with several artists, including Nan Goldin, Eisenman objected to the firing of Artforum’s former editor-in-chief David Velasco, following a letter he published in the magazine on October 19, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and describing the Israeli bombings of Palestinians as war crimes and genocide. The letter did not initially mention the October 7 attack by Hamas on Israeli civilians and was later amended. Eisenman removed her name from it and has said she would no longer work with Artforum for their firing of Velasco.

“I want to echo what activists have been yelling in the streets: Not in my name,” she told The New York Times in late October. “This war will not be done in my name. I resent these cowardly bullying and blackmail campaigns to distract everyone in the art world from the central demand of the letter, which was: cease-fire!”

Open Interpretations

Yet, even when her artworks are engaged in current affairs, Eisenman does not insist on how they should be read. Her artistic reckonings with social, environmental, and political upheavals remain open-ended and universal. On that note, occupying the center of the gallery, are two large figures peeled away from Eisenman’s more populated, monumental sculpture, Procession (2019), which was the star of the Whitney Biennial that year. They are androgynous, made with Eisenman’s signature, strange and unidentifiable cartoonish, smushed features—heavy, rounded hands, noses, and hooded eyes.

One bronze person trudges forward, barely pulling the other, who is bent on all fours, their head drooped, atop a wagon outfitted with square wheels. There is something rough and raw about their blurred features, which is unnerving, as though sprung from the imagination of a child who may not know what they are seeing, and wonders whether they should be frightened.

The piece was about Eisenman’s experience leading up to the Black Lives Matter movement, and those protests in which she participated. “You keep walking, sometimes with a fist in the air, that’s tired or broken. There’s a never-ending protest we have to show up for,” she said of the leading figure’s pose. She lends it a sense of optimism that runs through her work, but also a shared sense of melancholy and pain.

Installation view, ‘Nicole Eisenman. with, and, of, on Sculpture’ at Hauser & WirthParis, 5 June–21 September 2024. © Nicole Eisenman. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur

But removed from the rest of the Procession, the sculpture can also be interpreted as a relationship between two people, or a metaphor for one person pulling themselves along. “When it’s separated from this group, years later, we’re looking at a new story, one of moving through life, just trying to survive, or figuring out a way to do life,” said Eisenman.

Upstairs in the gallery, Eisenman displays works made by placing plaster, instead of paper, onto etching plates, in essence, to “conjoin my drawing and print-making process with sculpture,” she said. To the question she is often asked on how painting or sculpture interact or affect each other, she says “there’s no one way, of course, and I think that’s what this show demonstrates.”

Another example of this interaction is a large preparatory drawing for a sculpture in process, inspired by a 2020 painting. It depicts an immediately funny, impossible stack of figures, one on top of the other. At the bottom, a person carries a huge wine barrel tied to their bent back, as they reach forward to fill their glass from the barrel’s open spout. Next comes an enormous potato, and slouching on top of that, a large cat, followed by a seated woman, who pops up in another artwork in the form of a smiling Phyllida Barlow. She holds a vase of flowers atop her head.

“These are the things I need in my life,” Eisenman said of the pseudo-self-portrait. “It’s the basics: food, wine, art, something to show affection to, like a cat.”

Installation view, ‘Nicole Eisenman. with, and, of, on Sculpture’ at Hauser & Wirth Paris, 5 June – 21 September 2024. © Nicole Eisenman. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur

Like many of her pieces, this one is both funny and absurd, reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s writing, where characters wander through a kind of no-man’s land, for reasons they haven’t grasped. In both Beckett’s and Eisenman’s creations, little makes logical sense, but the effect is of something recognizable in ourselves.

“There’s humor in absurdity, it’s a crucial survival element,” Eisenman said, adding: “My painting doesn’t usually go into a surrealistic place. I want it grounded in our reality. I want it to be believable.”

Eisenman sparks this connection with her works, a subject she addresses in several contemporary genre paintings of beer gardens, parties, and demonstrators gathered in a park, as with The Abolitionists in the Park (2022). It’s a notion she also holds dear.

“I don’t believe in god. I could go on record saying that,” she said. “But there’s something else that becomes very meaningful to me, like … a spirituality located in human-based connections.”

Nicole Eisenman’s ”with, and, of, on sculpture””with, and, of, on sculpture” is on view until September 21 at Hauser & Wirth, Paris.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: