The experience of being the odd one out at school might have drawn him to Baldwin’s essay, he says. Although New York was and is full of black people, Ligon says he still found what Baldwin wrote about alienation and blackness mirroring his own feelings.

Later, he tried to incorporate ideas from what he read into his work, but found it difficult to do so visually.

“When I was a young artist, I was very interested in abstract expressionism, but there was no way to introduce the content of the books that I was reading into my artwork.”

‘A little looser’: sociable art at Supper Club event in Hong Kong art week

‘A little looser’: sociable art at Supper Club event in Hong Kong art week

The breakthrough came in the late 1980s, when Ligon and other artists, such as the feminist artist Barbara Kruger, began to appropriate images and texts created by others earlier. They recontextualised them in attempts to foreground marginal perspectives – in Ligon’s case, perspectives formed of his personal experience as a gay, black man in America.

His seminal work, produced between 1991 and 1993 and called Notes on the Margin of the Black Book, comprises framed, typed texts from diverse sources, including Baldwin’s writing, that are shown with copies of Robert Mapplethorpe’s idealised nude photographs of black men published in 1986 as The Black Book.

This work, now in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, draws attention to the complexity and intersectional nature of identities. Oversimplified identity labels are something that he continues to react against, in his now signature style of illegible, text-based paintings referencing 20th-century literary figures.

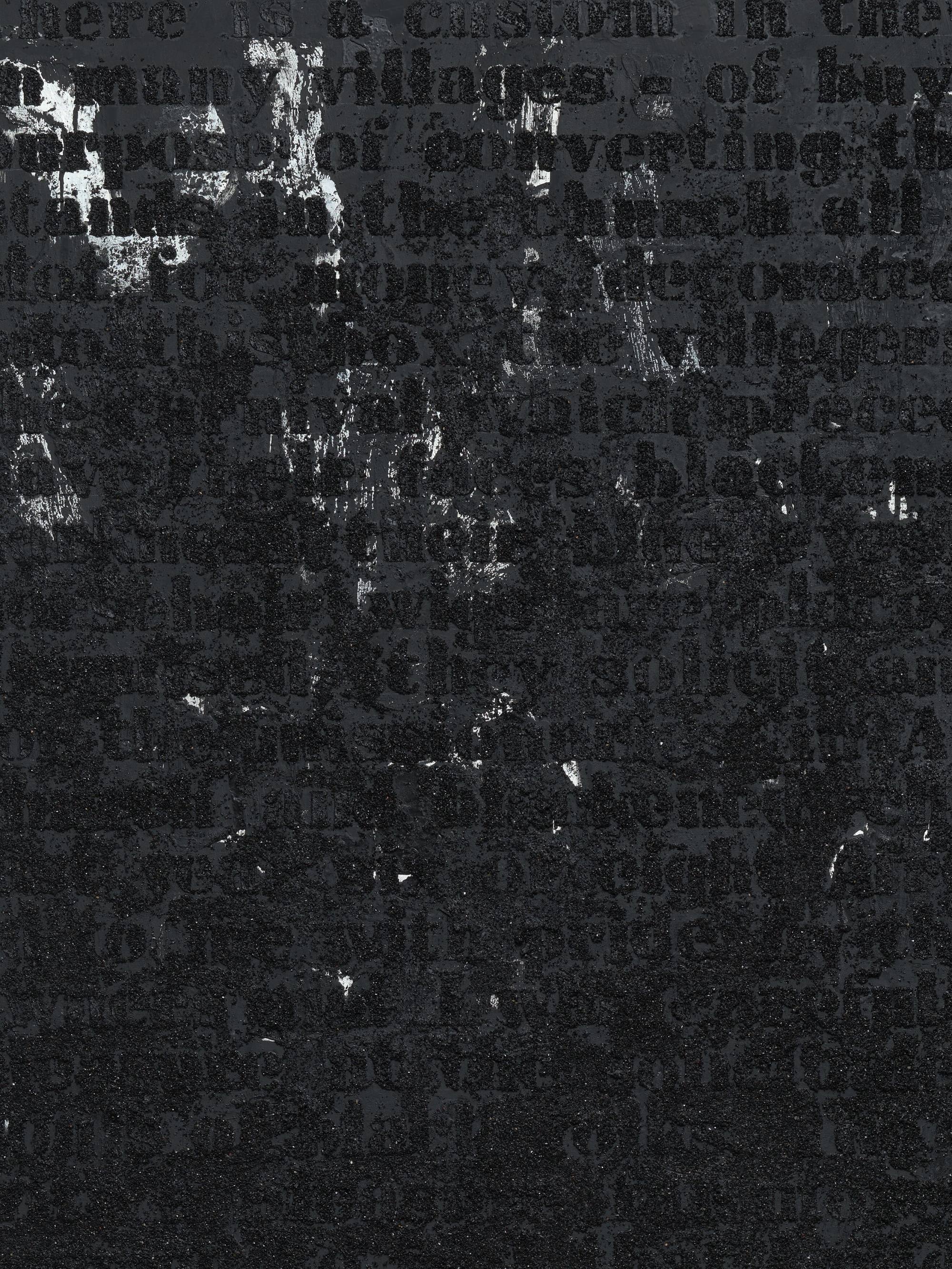

“I wanted to make very clear text [at first], but the use of oil paint makes messy text,” he says. “That was interesting to me. Where the letters, the words, the meaning break down through the act of writing is actually what the paintings are about.”

The paintings, he says, use various rendering techniques to depict the coexisting hypervisibility and invisibility in the black experience.

Making Baldwin’s exploration of colonialism and race hard to read serves two purposes, Ligon says. “The more you struggle with something, the more engaged you are with it,” he says.

Also, he wants to express the fact that ideas aren’t always transparent and clear.

He adds that the paintings are “about that struggle to make meaning and the back-and-forth between legibility and illegibility, abstraction and figuration”.

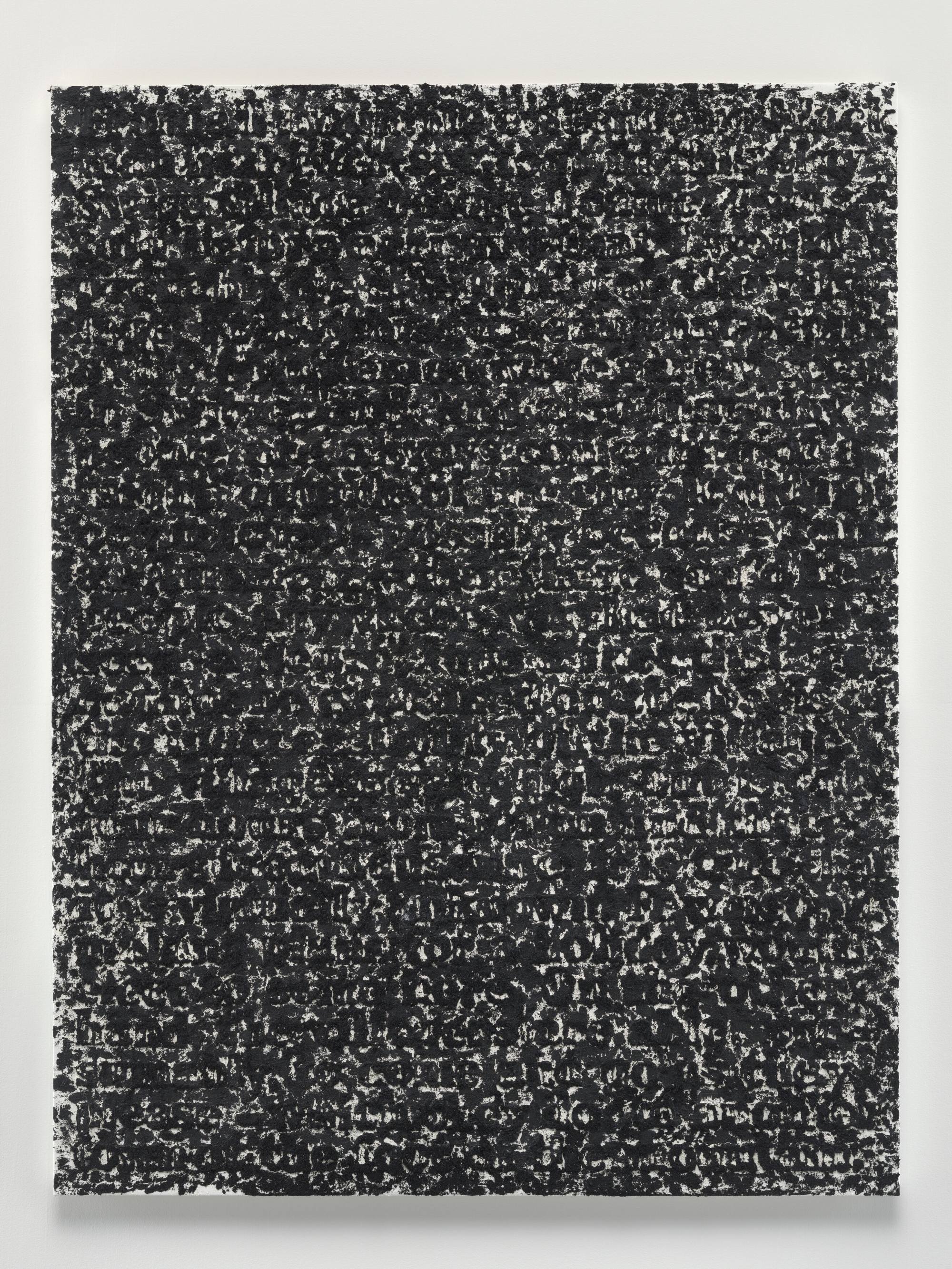

A more abstract body of paintings, titled Static, which he began last year, takes its name from the white noise on analogue televisions.

It’s funny to think that black culture can spread globally and have such an important impact, but that doesn’t always translate to how black people themselves are treated

Baldwin’s text is still there in the background, but it has been “taken to the point of static”, Ligon says. He started by painting white text on a white canvas, then rubbed a black oil stick across the surface.

“It’s a pure abstraction,” he says. “I feel like we are in a post-text, post-truth moment, at least in the US, where there are facts and there are ‘alternative’ facts. Language’s ability to convey meaning and truth is very much under question.”

Also on show is a series of untitled drawings on mulberry paper, which were inspired by stone rubbings he saw in Xi’an, in China. These are rubbings on top of a Stranger painting with carbon and graphite. The untitled works have different degrees of abstraction.

The curator Thelma Golden and Ligon were the first to coin the term “post-black art” in the late 1990s. Meant to liberate the then generation of black artists and creatives from the burden of representing their entire race and from being boxed in by racial identity, it became much criticised for underplaying the degree of racism that still exists in contemporary America.

“It’s funny to think that black culture can spread globally and have such an important impact, but that doesn’t always translate to how black people themselves are treated,” he says.

Western societies engage in a simultaneous incorporation and disavowal of black culture, he says.

In June, Hauser & Wirth will publish Glenn Ligon: Distinguishing P**s from Rain; Writings and Interviews, a selection of the artist’s writings and interviews with other journalists as well as his fellow artists over the past 30 years.

“Writing is a way to think more deeply about something, but making art is also a way to think about something – which doesn’t mean it’s easy. It’s as hard for me to make a painting as it is to write an essay.”

Ligon adds: “They’re the same level of difficulty, but maybe the same level of reward, too.”

Glenn Ligon at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, 8 Queen’s Road Central. From March 25 to May 11.

Additional reporting by Enid Tsui