The decades-old tradition of radical printmaking at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts is still going strong, with two exhibitions featuring bold colors and designs — and even bolder political statements — open through Friday.

Arte para el pueblo

The first, called “Arte para el pueblo” or “Art for the people,” features some 40 pieces created in the past year by Calixto Robles, the center’s artist-in-residence, as part of his $50,000 fellowship funded by the San Francisco Arts Commission.

The lion’s share of Robles’ recent artworks are posters made using printmaking. Printmaking broadly involves layering blocks of color on top of one another, which can be achieved in multiple ways.

One of Robles’ favorite techniques, called screenprinting, involves exposing photosensitive chemicals to light to create detailed stencils before applying ink or paint. Many of his works are created through a combination of several printmaking methods.

“I explore all the techniques,” Robles smiled. “I do etchings, linocuts, painting. I’m a self-taught artist, always experimenting. I like to play with my hands.”

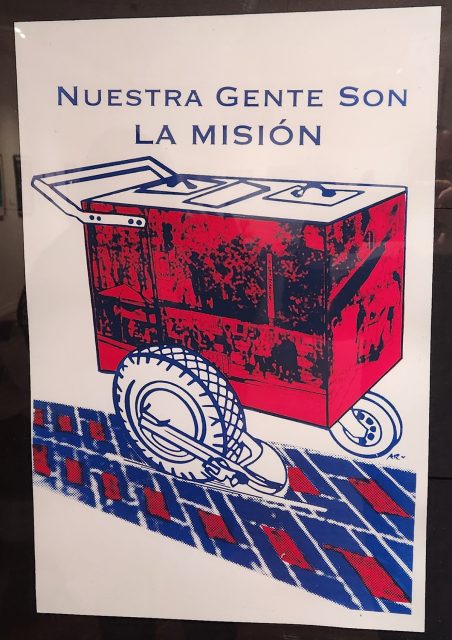

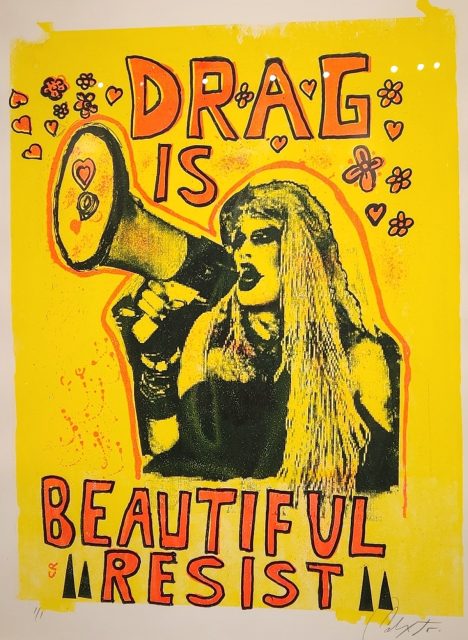

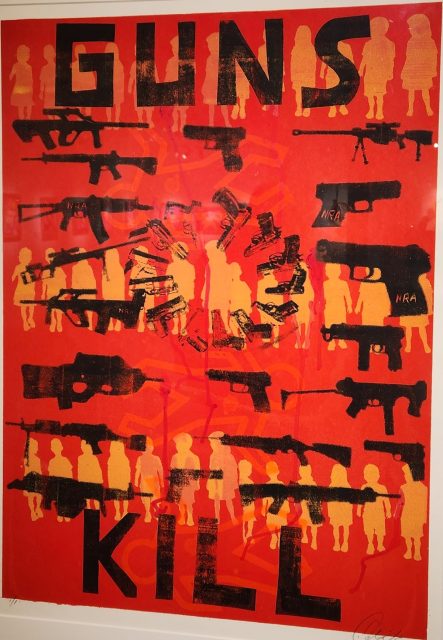

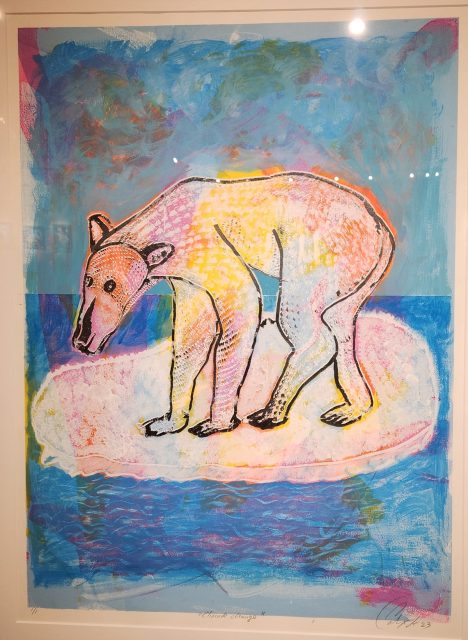

Robles has used his posters to comment on social issues, with designs that support drag artists, call for gun control and decry indigenous oppression. Printmaking is a particularly powerful medium for political expression, he said, because it allows messages to be spread en masse: “Printing gives you the chance to support different struggles: immigration, women’s rights, climate change,” said Robles. “I can do the posters and put them right on the streets.”

In fact, you may have seen some of his designs brandished by demonstrators in the Mission already — several have been printed up to 50 times to be given away during marches.

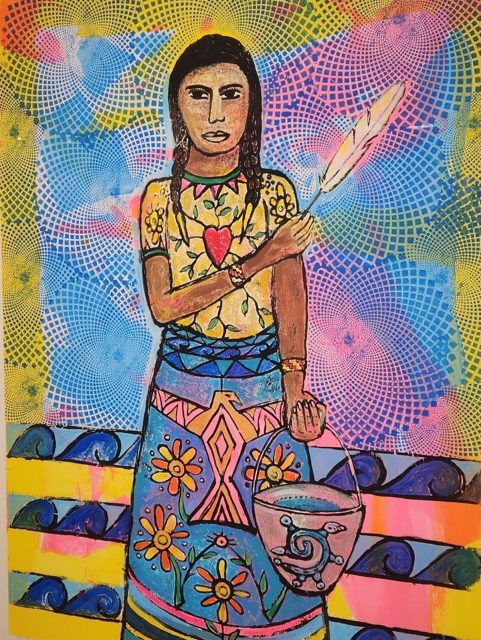

Robles, who moved to the Bay Area from Mexico in the early 1980s, also uses his art to reflect his indigenous Oaxacan heritage of Mixtecs and Zapotecs.

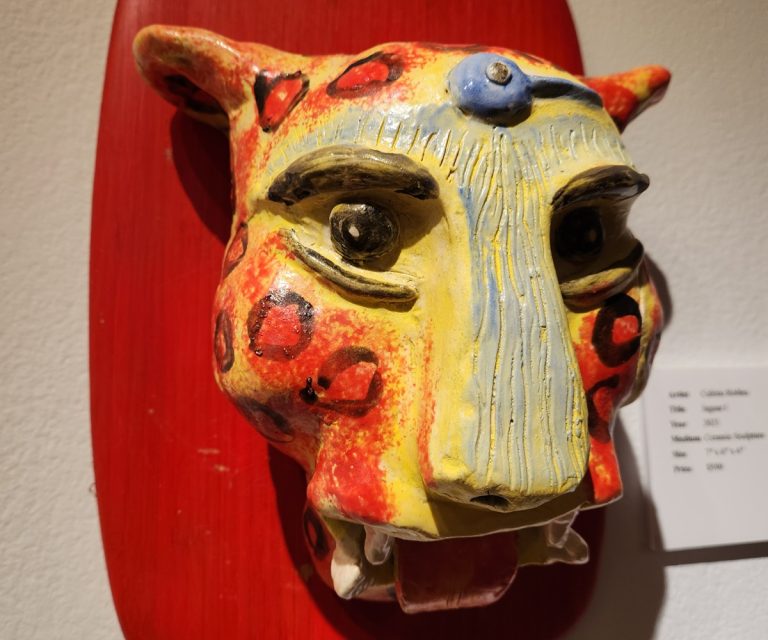

“They were great artists,” he said of his ancestors. “They created cities, paintings, ceramics, textiles. Those things, I think, are in my blood.”

Jaguars and hummingbirds therefore appear in lots of his paintings — although nowadays, he added, he also likes to include motifs from other cultures, such as lotus flowers or depictions of Native American ceremonies.

“I started studying the struggles and the way they have been robbed by this government for their lands, their rivers, their culture,” he said. “It’s the same thing that happened in Mexico with the native people.”

Including other indigenous cultures in his art is a form of solidarity, he said. In his recent work, he added, he has gravitated towards “spiritual” imagery like angels, to provide a positive contrast to the fierceness of his jaguars.

Chismosas

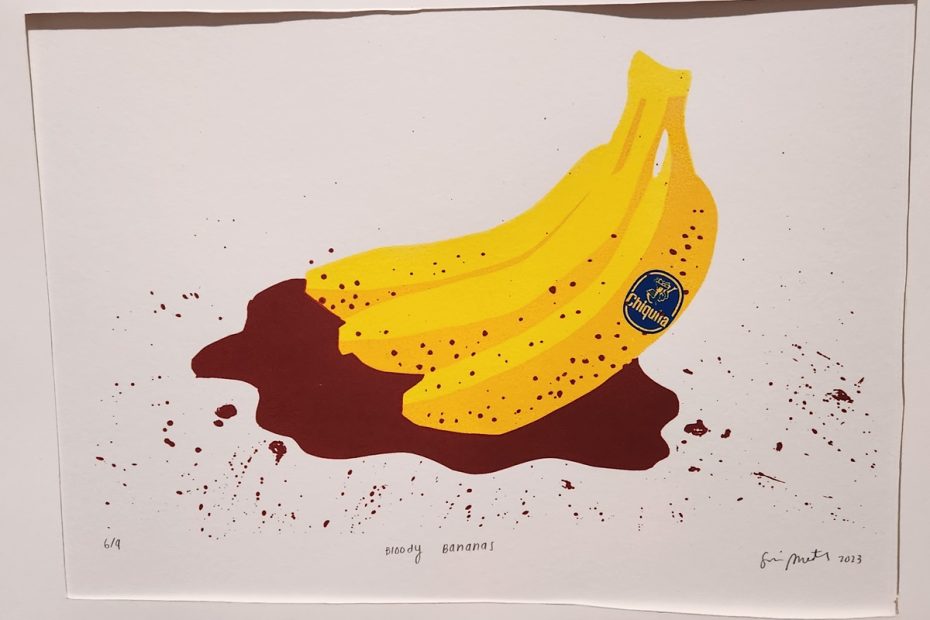

The second ongoing exhibition is called “Chismosas,” roughly meaning “women who gossip.” It was jointly put together by artists Alejandra Rubio, 26, and Sarai Montes, 23, and is based on the art they created during their apprenticeships at the cultural center.

“Generally the word has negative connotations,” explained Montes. “We were trying to redefine what it means to us. Sometimes conversation may be dismissed as gossip when really we’re dealing with very important topics.”

As with Robles’ exhibition, the bulk of the individual pieces are political posters created using a variety of printmaking techniques. But in “Chismosas,” the physical context of each individual artwork is just as important as the art itself.

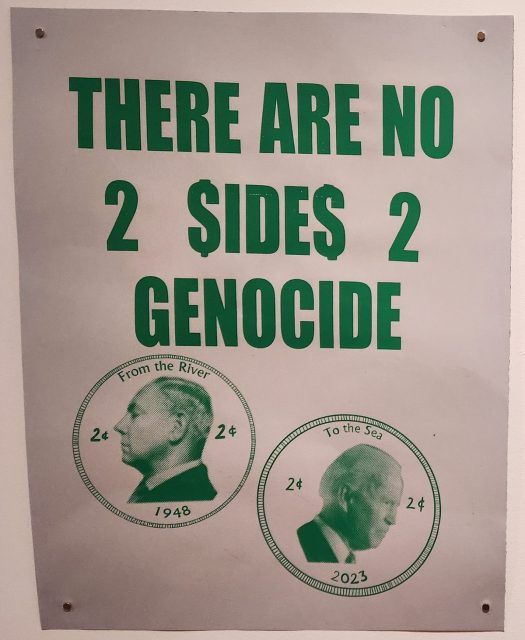

The pair have outfitted their gallery to look like a living space, complete with a set table in the “kitchen” and sofas and a TV in the “living room.” Symbols of typically feminine domesticity — embroidered tablecloths and pink floral crockery — are mixed in with the overtly political posters, which call for an end to gender-based violence and the war in Palestine.

The artists decorated the gallery with items from their own homes, including photos of themselves, cementing the link between hard-headed politics and personal, domestic space.

Local and global struggles are both given consideration. In one corner, one piece by Rubio tackles street vending in the Mission, while another directly next to it confronts killings in Gaza. Activism is depicted as something immediate and concrete, not abstract.

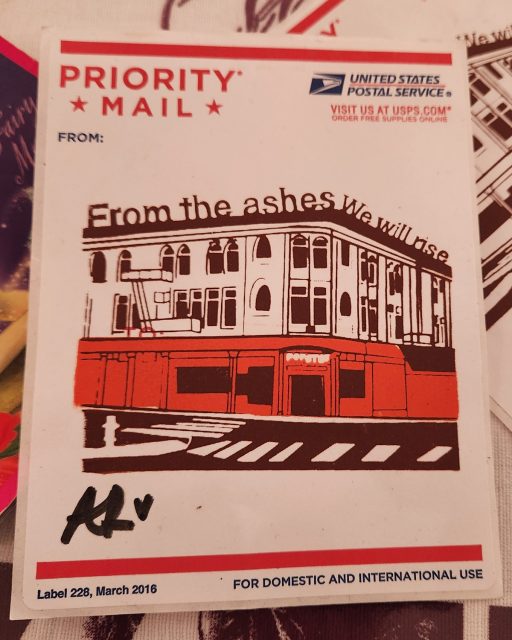

For example, Rubio recalled how she had watched the building at Mission and 22nd burn down from her apartment window in 2015. The incident spurred her to create a piece titled “From the ashes we shall rise,” with a printed depiction of the old building.

The artist had been a young activist against gentrification: “When I saw the building burned down, it was just one of those moments where the concept became real.”

The exhibitions will be up until Friday, Feb. 23, and the gallery is open from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. on the weekend, and 2 p.m. to 8 p.m. on weekdays. Group tours and reservations are also available by appointment.