Artist Roy Nachum triumphantly climbs and stands on a rock, as we take in the beautiful nature around us created virtually and projected onto the walls and floor of the main hall of his new museum in lower Manhattan. I take a seat on top of the foam stone and look at the only other “real” objects around—swings on either end of the room.

“It reminds us of Central Park, of those rocks,” Nachum said of the foam objects. “It gives you that memory and you can lean on that. When you lean on that memory, then [the technology] doesn’t feel so strange.”

It is a grand entrance for the artist’s forthcoming 36,000-square-feet museum, located in the former Century 21 department store space near the World Trade Centers. Now in its soft opening, Mercer Labs: Museum of Art and Technology has been in the works for six years and was created with Nachum’s business partner Michael Cayre, a real estate developer.

Rihanna and Roy Nachum at the artwork reveal for Anti at MAMA Gallery, 2015. Photo by Christopher Polk/Getty Images for Westbury Road Entertainment LLC.

Nachum, a multidisciplinary artist primarily known for his surreal but hyperrealist paintings, rose to fame with the cover he designed for Rihanna’s 2016 album Anti. The artwork, titled If They Let Us, included the braille text of a poem written by Chloë Mitchell and featured Nachum’s signature Crown Kid character. The original paintings Nachum created for the album are in Rihanna’s private collection, while the crowns are featured in his new museum.

He said the Crown Kid “serves as a symbol of humility and equality” and the Braille another medium to communicate through language. “The tactile quality allows for interaction otherwise not allowed in painting,” he said.

“My work by its nature demands interaction, and I believe that both consciously and unconsciously this notion has grown to feed the dream and movement behind Mercer Labs, where technology is the tool and the viewer is invited to experience the work from another point of view,” he added.

With Mercer Labs, the artist hopes to encourage people to ponder themes from equality for those with visual and hearing impairments to the encroachment of technology and artificial intelligence into our lives: “Everybody here deserves an equal chance to enjoy and really experience the moment.”

An installation of a robot that writes messages in sand inside the Mercer Labs Museum in Manhattan. Photo courtesy of Mercer Labs.

In the first room, Nachum introduces the braille motif that is woven throughout the museum. However, the braille is, in most cases, projected light and so not actually tactile or useful for people who are blind. But, in one room, Nachum included a handful of his signature hyperrealist paintings with embedded braille that can be touched. He explained the motif as a callback to his early career when he first moved to New York from Israel.

“I created paintings that included burnt charcoal, so the people individually touched the work and it leaves evidence,” as the charcoal smears across the canvas, Nachum said of his earlier work. “So now I encourage people who are visually impaired to touch all my paintings.”

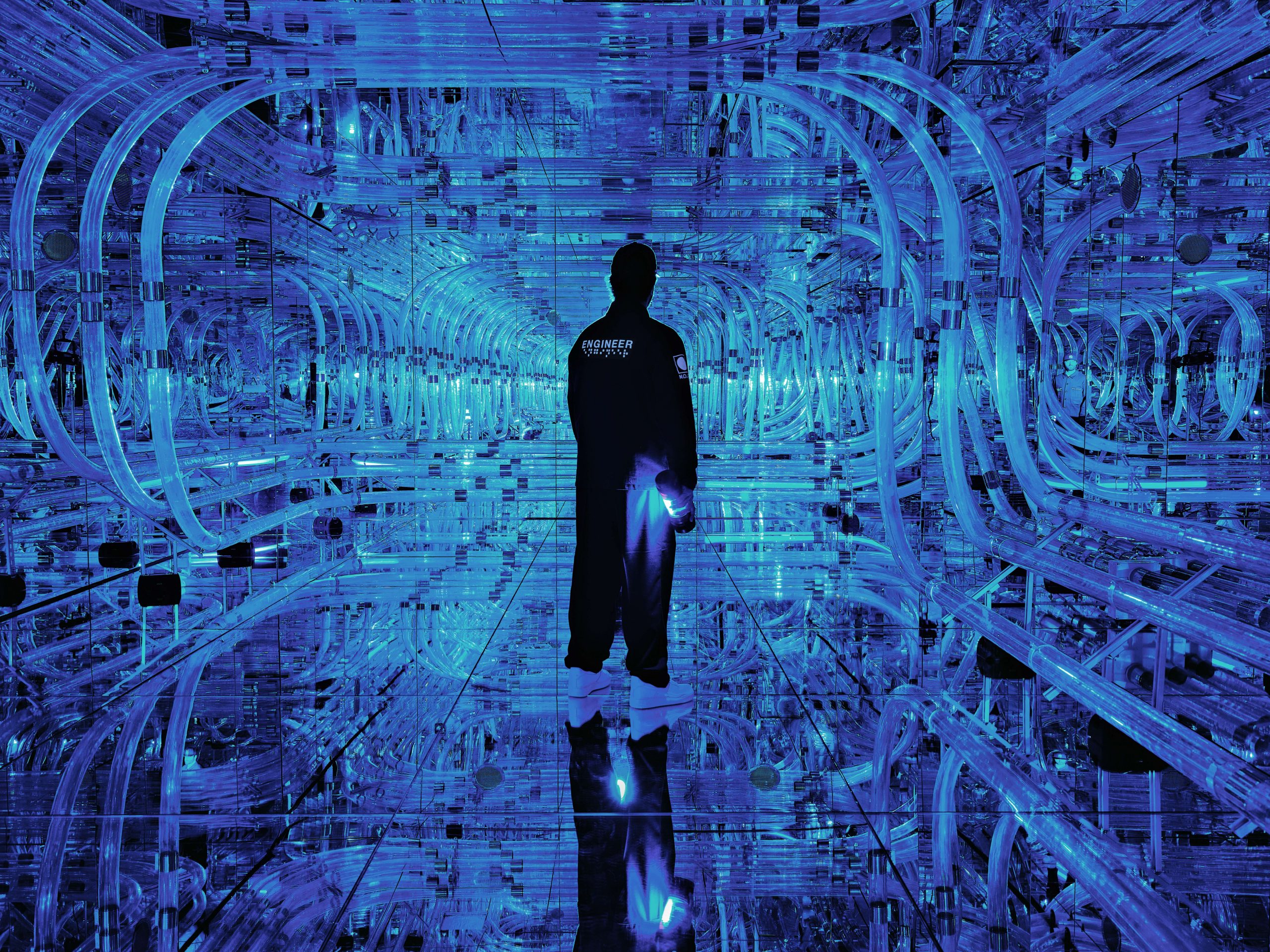

A view inside the Mercer Labs Museum in New York City. Photo courtesy of Mercer Labs.

Up the stairs, Nachum led me to a room where I was instructed to put a blindfold on—a natural equalizer for those who can see and those who can’t. The blindfold bore the text “I SEE SOUND.” The room was mostly empty apart from mood-setting lights and pillows on the carpeted floor. I fashioned an eye mask to my face and plopped onto the floor. The space around me filled with sounds—mostly recognizable nature-scapes of rushing water, rain, and jungle animals.

Here is where Nachum’s efforts towards inclusivity are realized. The artist has embedded 36 speakers under the elevated floor. Because of this, the floor vibrates and rumbles with definition. A deaf person could likely, for example, follow the movement of a tiger as it moves through the space roaring. It is meditative, like listening to guided imagery to allow one experiencing it to create any visuals in their head.

“We have to create it in real time in the space to really understand how to move sound through it. You cannot really plan ahead,” Nachum said, adding that really most of the museum’s installations had to be designed on-site once the building was secured. He recreated the museum 35 times during the process until he was happy with the end result. “There is a way to tell a story to really engage people. So, it has to be a certain way.”

In another room, Nachum has created a large-scale holographic installation which uses 500,000 individual LED lights, hung on strings and equally spaced apart, like pixels. With this, Nachum creates three-dimensional videos, from a galloping horse to flickering fire. The lights are placed in an infinity room, which explodes the piece to a grand scale that feels otherworldly. It’s his first time working with such an installation at this scale.

The outside of the new Mercer Labs Museum is seen in New York City. Photo: Adam Schrader

And from there, Nachum took me to another room targeted at children. (The artist has two children of his own, a nine-year-old and a three-year-old, with his wife Maia, who have all been involved in the creation of the museum.) In this space, children can use available crayons to color in images of dinosaurs. These are then quickly scanned and become three-dimensional digital creations that will permanently live in a digital environment created by Nachum. Also included is a ball pit and a giant chess board, created from hand-carved wood and 3D-printed resin, which reacts when trod on.

“Kids are so inspiring,” said Nachum. “They’re so innocent. If they want to jump on a table, I let them jump on a table. There’s a lot of restrictions in life so in here there are no restrictions. You can touch the work.”

The next room is filled with plastic flowers and screens showing a very pink scene with monkeys howling on screens embedded among the floral arrangements. In this room, Mercer intends to serve flower-flavored drinks, bringing taste into the equation.

A view inside a floral pink room at Mercer Labs. Photo: Adam Schrader

All in all, the range of the technology utilized in the space is vast, ranging from the editing of light and directional sound to robotics and A.I. In one room, visitors type a message on a tablet screen that is then sent through a pneumatic tube array. The device that carries the message through the pneumatic tube has a screen that visually adapts to the message sent using A.I. Nachum encountered a problem with physics in the creation of the room: “We had to find so many different solutions.”

He added that he hopes to collaborate with musicians and other artists, such as Drift, the artist duo opening a museum in Amsterdam to house their epic installations.

Asked about whether he found it risky to open an immersive museum when some others have struggled with maintaining interest and slowing finances, Nachum was unequivocal. “I don’t see it as immersive,” he said of Mercer Labs.

“It’s not just about projectors. It doesn’t have to just be video mapping technology,” he continued. “To me, it’s a space that we can collaborate and change the canvas all the time.“

Mercer Labs has opened in preview at 21 Dey St, New York, with limited time slots available.

More Trending Stories:

A Case for Enjoying ‘The Curse,’ Showtime’s Absurdist Take on Art and Media

Artist Ryan Trecartin Built His Career on the Internet. Now, He’s Decided It’s Pretty Boring

I Make Art With A.I. Here’s Why All Artists Need to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Technology

Sotheby’s Exec Paints an Ugly Picture of Yves Bouvier’s Deceptions in Ongoing Rybolovlev Trial

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.