The artist Roni Horn considers herself an “off brand” in more ways than one.

“I’m not even sure I’m a visual artist,” she said recently during a visit to her large Manhattan studio, incongruously located in a high-end Chelsea apartment building.

Those statements may sound self-deprecating coming from someone with four solo exhibitions at galleries and museums this spring, an unusual number for any artist.

But Horn, 68, an intellectually peripatetic Conceptualist, has an innate confidence, which may stem from the fact that she does not feel she fits in anywhere, personally or professionally, and never has. So she simply follows her ideas wherever they lead her — what’s the worst that could happen?

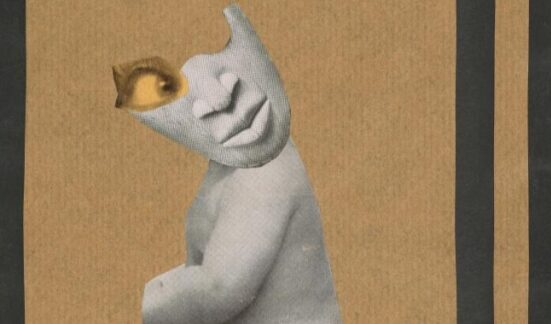

The results she achieves seem to have few stylistic similarities. The serene, Minimalist cast-glass sculptures do not seem to be by the same person who produced those playful text-based drawings, or the suites of paired photographs. Sometimes her work reveals her hand; more often it is fabricated to her specifications.

“So much of the art world is about branding, and Roni’s work isn’t that,” said Poul Erik Tojner, the director of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek, Denmark, the site of one of her upcoming shows.

Her great subject turns out to be the malleability of identity itself, which may help explain why Horn describes an exhibition as a “group show of myself.”

Over a nearly 50-year career, she has returned again and again to the concept of doubling, as in her 1997 diptych “Dead Owl,” twin photographs of a stuffed snowy owl. A solo show organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Tate Modern, which ran from 2009 to 2010, was called “Roni Horn aka Roni Horn.”

“Fluidity of identity was always something I always related to myself,” Horn said. “I was not a fixed thing. I was very stable, but I wasn’t fixed.”

From that complex idea comes work with a pared-down quality. “Her work is so distilled,” said the artist Matthew Barney, a friend of Horn’s. “She hones it down until what’s left is presence. There’s no extra baggage.”

Horn’s longtime gallery Hauser & Wirth is featuring her twice this season. At one of the gallery’s New York locations, in SoHo, a show of her work (through June 28) features six luminous cast-glass pieces as well as 14 works on paper made with graphite and watercolor, which she calls “diced” because she cuts them up and reassembles them.

A show at the gallery’s branch on the Spanish island of Minorca opens on May 11 with a variety of installations and sculptures, including “Asphere” (1988/2006), a patinated copper sphere that is slightly askew.

In addition, she has two major European museum surveys. “Roni Horn: Give Me Paradox or Give Me Death” is on view through Aug. 11 at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, while “Roni Horn: The Detour of Identity” runs from May 2 to Sept. 1 at Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. “Detour” pairs her work with clips from classic films.

That both museum shows are outside the United States does not surprise Horn.

“Most of my work has not been collected here, with the exception of Glenstone,” she said, referring to the art museum in Potomac, Md., founded by the collectors Mitchell P. Rales and Emily Wei Rales. “I’m not a must-have artist. I’ve never been hot.”

Horn lives in Greenwich Village, and has a home on Maine’s Mount Desert Island, too. She loves remote places, and for many years spent much time working in Iceland.

Seated in a separate room of her studio hung with works by other artists — including Matthew Barney, Philip Guston, Weegee, Ed Ruscha, Louise Bourgeois and Vija Celmins — Horn fidgeted as she talked about her life and career. She kept picking up a notebook, but never made a single mark. If her muse happened to call, she was ready.

“Most of my art I see as a workaround,” she said of the circuitous routes she takes to a finished piece. “Improvisation and workarounds.”

That day she was working on what she called a “weird drawing”: The letters of the word “spirals” had been rearranged on it over and over.

“It just came out of nowhere,” she said. “Even if it ends up making no sense, I thought, ‘Let’s check it out.’”

Even at a time when attitudes about sexuality and gender norms are shifting, Horn’s way of talking about herself stands out. She has long eschewed most labels. Asked if she is married, she said, “Technically, yes, but I don’t partake of the institution.” (Julia Todoli, whom Horn prefers to call her partner rather than wife, is a schoolteacher.)

Horn, who came of age in the 1970s, recalled navigating a culture that did not seem to have a place for her. “I was kicked out of women’s bars plenty of times, because people thought I was a man,” she said, adding, “I was not able to not be androgynous.”

Instead of picking a subculture, “I just floated,” she said, partly because she’s not a very social person to begin with.

“She made gender a theme in her work,” said Glenstone’s director, Emily Wei Rales, adding, “and she fought for it.” Rales, who organized a 2017-18 show of Horn’s work, observed: “She is who she is, and she’s not apologetic about it.” The museum’s collection includes the cylindrical cast glass work “Water Double, v. 3” (2013-15), another twinned piece.

Horn’s glass works have become a signature, and they appear in all four of her spring shows. Made with optical glass, they can weigh up to five tons. Horn, returning to the idea of doubling, said, “It has this mischievous appearance as a solid, but technically it’s a supercooled liquid.”

Viewers often think the pieces are made of water, and they elicit a strong response. “They are ineffably beautiful,” said Horn’s friend Tacita Dean, the British artist. “And I just think they’re unbelievably, sensually female, too.”

Giving aesthetic pleasure is not always considered a plus for a Conceptual artist.

“I get criticized for their being beautiful,” Horn said. “But I think that the beauty in them is a manifestation or an artifact of this concept that I’ve developed.” In other words, it’s a byproduct and not the point of the work.

Horn was born in Queens and raised partly in Rockland County in New York. Her mother had various jobs, and her father was a pawnbroker; his dealing in jewelry helped inspire an important early work, “Gold Field” (1982), a sculpture made out of thin sheetlike layers of gold foil. “Maybe I got the pawnbroker’s daughter thing out of my system with that one,” she said.

Horn’s father gave her a camera from his pawnshop, and her parents “set a value” on things like taking her to the Museum of Modern Art.

Seeing the Northern Lights as a child also made an impression, setting her on a course of nature-themed works, notably “You Are the Weather” (1994-96): 100 photographs of a woman sitting in hot springs in Iceland, with a slightly different expression in each image. A series of related photographs, “Untitled (Weather)” (2010-11), are in the Louisiana Museum show.

“The works use weather as a barometer of feeling,” said Donna De Salvo, a former chief curator at the Whitney who helped curate Horn’s solo show there.

“She has different weapons, and repetition is one of them,” Tojner of the Louisiana Museum said of Horn’s penchant for iteration. At the show in Denmark, visitors will find “Portrait of an Image (with Isabelle Huppert)” (2005-06) — 50 images of the French actress stacked in rows.

When Horn was pursuing her B.F.A. at the Rhode Island School of Design, her thesis project, titled “Ant Farm,” used real ants, which she said was probably the earliest sign of her fearlessness in trying new materials.

“The ants were really about social culture,” Horn said. “The ants created, in effect, a drawing in the earth.” She added, “Drawing, for me, is the core activity.”

For her M.F.A. at Yale, Horn chose sculpture as a focus partly because that meant she would not be tied down to a specific material, keeping her options open as always.

She had her first solo exhibition, in 1980, at Kunstraum, a nonprofit space in Munich. Later that year she had a show at the Institute for Art and Urban Resources (the predecessor of MoMA PS1), where she exhibited her first doubled work, “Pair Object I” (1980), made from two copper rods.

She has returned frequently to installations of leaning rods against a wall, often covered with text, as in “When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes: No. 859 A DOUBT IF IT BE US” (1993/2007). That work, from her series highlighting the poet, is included in the Cologne show.

Over the years, Horn has become particular about how her art is installed; just because she has mined ambiguity in her work does not mean she lacks strong opinions. “Anybody who works with me knows that I’m the curator,” she said.

Rales recalled that for the 2017 Glenstone show, Horn made a detailed drawing of exact measurements of the space.

“When she got here, she said, ‘That ceiling height has got to change, and that wall has to go here,’” said Rales, who has become a close friend of Horn’s, as has her husband. “She likes control, but I could also sense that she was right.”

De Salvo said that Horn’s outward toughness contrasted with the work itself: “Roni infuses it all with tenderness and vulnerability. She lays bare quite a lot.”

But the form of that expression may well change from piece to piece, summed up by the work that gives the Louisiana show its name, a text-based gouache titled “The Detour of Identity” (1984-85).

Horn acknowledged that for casual viewers, she “doesn’t maintain an entrance point to the work” — visually speaking — “and that’s why I lose my audience.”

The prospect of losing viewers might make some artists zig or zag, but Horn is already in the detour business.

“Even if something is popular,” she said, “I’m still moving on to something else.”