It was the early ‘90s and the Mission was boiling, fermenting with artists from all over the world. At least that’s how Clarion Alley’s Project co-founder Aaron Noble recalls it — an artistic melting pot. And one of the premier artists at the time — a painter fueled by coffee, tobacco and burritos — was spray painting institution Scott Williams.

Williams, who lived at his apartment at 20th and Shotwell for 35 years, died Sunday, May 26, at San Francisco General Hospital. He was 67 and succumbed to an infection, according to his family.

Williams was one of the first artists to paint a mural in Clarion Alley after Noble and other artists started the project in 1991, Noble said. The two cultivated a friendship that lasted through the ‘90s before Noble moved to Los Angeles in 2000.

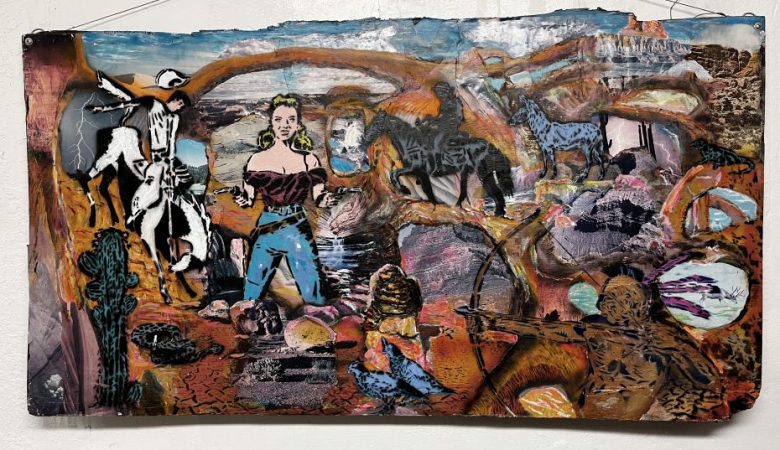

“His work was everywhere, literally out on the street and indoors and outdoors, on cars driving by. You couldn’t avoid it,” said Noble. “He was a stencil artist. He was the stencil artist. He was the greatest of all stencil artists.”

Some of Williams’ stencil pieces sat at local favorites, such as Burger Joint, Leather Tongue Video, Pedal Revolution, Chameleon Bar, Armadillo’s on Fillmore, DNA Lounge, Amoeba Records and The Lab. Mission Local found that his painting at The Lab was the only one remaining.

Williams started using stencil in the early ‘80s when he cut images from magazine images and glued them on pages of a notebook.

“I had this idea in the back of my mind, ‘What if I was to take a photograph and cut out all the dark parts and spray paint through that? I wonder how that would look.’ I remember thinking about that for several months,” said Williams in the 1991 documentary Spraypaint. “I thought this might not work, so I won’t spend much time on it and I just did it really quickly and sprayed it once and I was surprised how well it came out.”

Williams was born in Los Angeles and grew up in Santa Barbara. He arrived in San Francisco in 1979 and started doing stencil work shortly afterward. He received the 2005 Adeline Kent Award, which recognizes promising artists in the state, and his work has been featured at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and the San Francisco Art Institute.

After more than a decade using spray paint, Williams switched to an airbrush machine in the early to mid ‘90s because the latter was less toxic, some of his friends said. Toward the end of his life, he returned to making collages in books.

“Recently, he showed me a series of 8.5” x 11” pages he’d been working on since 2020, his pandemic series — abstract magazine scraps collaged, around 50 pages in all — no people, no text. Brilliantly dense stuff which rivals earlier spray stencil abstract work,” said his friend and client Robert Collison.

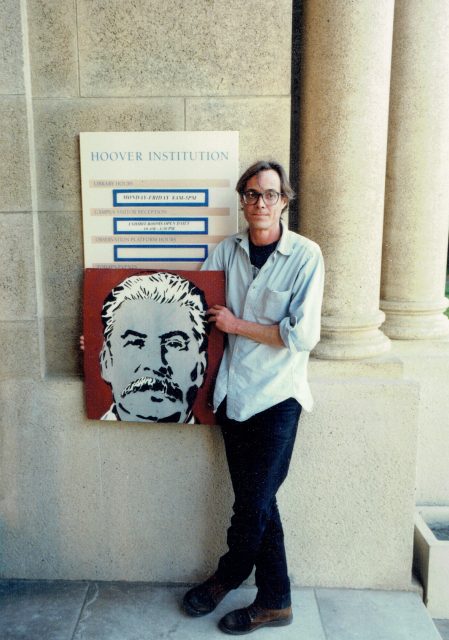

Friends described Wiliams as smart, soft-spoken and well-read — a Marxist who thought Lenin was under-appreciated. One of his pieces is a portrait of the trio Lenin, Marx and Colonel Sanders.

He liked super carnitas burritos from El Farolito, Cafe Bustelo, Export A’s cigarettes, crusty sourdough and an occasional Negra Modelo. He hated sports and television — though he did sometimes use the latter as a metaphor.

“You watch television and things are changing irrationally from one point to the other, from 500 dead in China to a dog food commercial,” he said in SprayPaint. “That’s a dominant feature of our culture, these images are hitting us one after another and not in a particularly sensible order. Maybe if you stood back far enough from it there would be a point where it would make sense.”

Annice Jacoby, a writer, artist, curator, advocate for public art and author of the 2009 book “Mission Muralismo,” said Williams’ work is complex and mysterious, an oeuvre that commands attention.

Comparing him to “Andy Warhold or Robert Rauschenberg or any of the so-called fine artists” of the late 20th century, Jacoby said he was “just as avant-garde, but directly in the street at the same time.”

“He also had some sense of ‘no surface was safe’ just like Michael Roman, a mixture of political imagery, pop culture and juxtapositions,” she added. “He definitely was kind of the king of it at that time.”

Noble recalled his “amazing library of imagery” that Williams called “stored energy.” “It was this surrealist mashup with pop cultural images from all different eras and different mediums all mashed together in a timeless, flickering, vibrating, interdimensional collage.”

Russell Howze, the author of the 2008 book “Stencil Nation” and founder of stencilarchive.org, met Williams in the early 2000s after documenting his work throughout the city. For years afterward, he visited the artist’s apartment to photograph his work, images he would eventually use for his website. He remembers him as a teacher and mentor, a person who deflected talking about his art.

“He seemed meek and mild but if you look, his art was very bold, very strong. He wanted to fill in every last millimeter of space and he just took these normal, mundane clips of art and created these otherworldly pieces,” said Howze. “He definitely had this punk aesthetic. He was right there in the middle of all of that in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.”

Punk is how longtime friend and fellow artist Fred Rinne met Williams in 1981.

They were both fans of the Cramps, a band with New York and Sacramento roots, and became “darn near family, a tribal family” to one another, said Rinne. “It all happened because of punk rock.”

William’s death came as a surprise to his sister Lissa Williams, who spoke to her brother a couple of weeks before he died. She recalled her brother as “very entertaining and very good at telling me stories,” and said he had been feeling better and ready to go home.

She said he would have been happy to read at least one of the latest headlines: “He would have been so happy to see that Donald Trump was found guilty.”