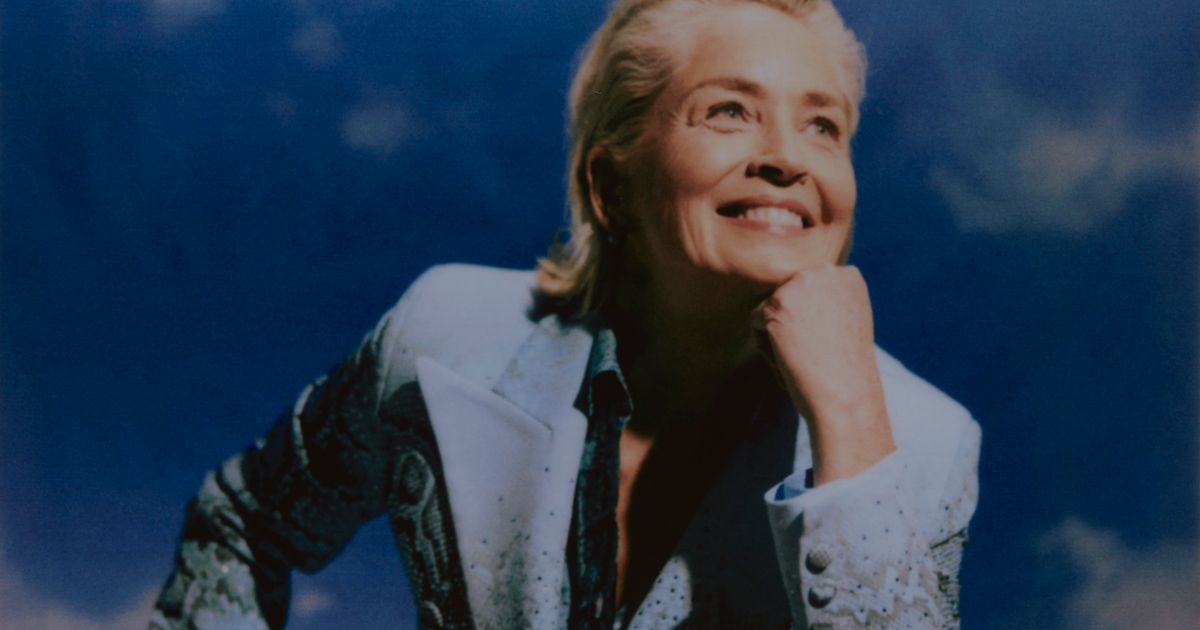

The artist in our 2023 Vulture Festival portrait studio.

Photo: Chantal Anderson

John Waters once talked to me about “The curse of fame.” He was referring to the difficulty, the near-impossibility, of anyone not deeply immersed in and of the art world — an actor, a musician, etc. — to be taken seriously by the art world. Usually such people are looked at askance, or not looked at at all. They’re treated as novelty acts, ones that exist outside the serious insider art world.

As someone with no degrees, who never completed school, who did not begin writing until I was 40 and taught myself to write in public, I am interested in people who took similarly unconventional routes to finding their own voices and modes of expression. Sharon Stone is one of these artists. I first noticed her work during the pandemic when she began posting it on Instagram. Here was this personage, this legend, this star, painting. Like many of us during the height of COVID, she had withdrawn into a condition something like the caves. She worked at home, in what looked like her bedroom, with things close at hand, using materials that were around. And she worked constantly. She was covered in paint.

At first I just watched. I was amused, thinking, Fun. Another movie star who paints. Then I kept watching. She kept working. Stone is among the most looked-at people alive. Here she was alone. Working, and growing. Often with nonartists, they find a trick or gimmick and repeat it. This was not happening. I thought of Jim Carrey, who in 2016, after the onset of our long American night, began making drawings of Trump. This was at a time when few from his industry dared speak up. I interviewed Carrey at Vulture Festival in 2018, and he recalled his team advising, “Don’t do this.” In him I found a passionate activist artist. It was not altogether different from when I saw the paintings of one of the worst Americans who ever lived, George W. Bush. After plunging America into the abyss, he began to paint himself naked alone in a bathtub, wiggling his toes; himself in a shower, peeking at us in a little mirror. It made me think of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell. I knew I had to write about him.

Few have had as much taken away from them as Stone. In 2001, not long after we witnessed annihilation on September 11, Stone suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage — a serious brain injury. It went undiagnosed for nine days, her bleeding into her own brain all the while. An experimental new procedure was undertaken to save her, one that has left her with 23 platinum coils in her brain. For a time she lost the hearing in one ear, was unable to walk, her face had fallen in, she was unable to speak — and when she did relearn to speak, she had a stutter. She saw colors, hallucinated.

This is a person who had raised considerable sums of money for AMFAR; who had been recognized for her AIDS advocacy; who had prominent roles in a number of enduring films. Even so, she stopped being offered parts. She was alone. She had “lost her place in line,” as she put it. Then her world was taken away. She lost her beloved child in a custody suit. And she continued to contend with the reality that to many people, her entire career could be reduced to a Basic Instinct scene in which for one-sixteenth of a second her genitals may or may not have been visible.

During a breathtaking and candid hour-long conversation at this year’s Vulture Festival in November, Stone revisited these moments with me, drawing a line from her assorted traumas to the work she’s now producing as a painter. As she puts it, “Style is what you do with what is wrong with you.” She took all of these life events, everything that was taken away, everything that was given, and she learned to breathe and to forgive. In a sort of mystic unraveling, I see an artist, someone living a life in art. Being a freedom machine. It is easy to shun the work of movie stars. No matter. Stone understands that, explaining, “I am not ashamed; I am unblemished; I am pure in my heart and in my soul. I am not bitter; I am not sad; I have no need to be washed clean; I am not angry … We can survive anything. Everything.” She more than survives.

You opened your memoir, The Beauty of Living Twice, with a poem from Emily Dickinson, the one that begins, “Because I could not stop for Death, he kindly stopped for me.” Why did you start your book with this otherworldly piece of writing?

Well, I’ve had this weird experience of having a lot of death experiences in my life. I was hit with lightning when I was a kid. I must have been 16? I grew up really, really in the country — like, kids drove their tractors to school after they finished their chores. I was ironing, and I had my hand on the faucet and the iron, and lightning hit the well. It literally knocked me across the kitchen, and I hit the refrigerator and was just out. My heart stopped. And my mother — not that this was unusual for her — belted me. She hit me across the face as hard as she could. That brought me to, and then she took me to the hospital. I had to be on a heart machine for about a week because it gave me an arrhythmia.

A couple of years before that, I was breaking a wild horse in our side acreage and the horse took off. My mother was hanging sheets on a clothesline and the horse took me under the line. I was nearly decapitated. My neck was really badly cut open. And then I had a stroke and nine-day brain bleed when I was 41.

Can you talk a bit about that? You actually got into the carriage with death.

Yes. I couldn’t get to the hospital right away, and when I eventually did, I was put in an MRI tube, where I fell unconscious. When I woke up, there was no one in the room but my doctor, and he was quietly stroking my hair — which is never a good thing. I looked at him and said “Oh, I’m dying, aren’t I?” And he said, “You’re bleeding into your brain.” I called my mother and my best friend. And then suddenly, I was … traveling out of my body, up into this — I don’t know how to quite explain it — this chasm, this tube of white light, and I could see people who had passed away, close friends looking down at me, smiling at me. I felt like I was going to them.

And then I felt like I was kicked in the chest, really hard. I don’t know if they defibrillated me, but I [intake of breath] and sat up. I went into the bathroom and peed for what seemed like an hour. I just felt so out of my body. They sent me to a hospital where I wasn’t in a regular kind of intensive care; I was in this room where we were all just separated by drapes and there was a nurse’s station in the middle. There were about ten of us, and it was right after 9/11.

So the whole world was traumatized.

It was awful. Some people were dying and some were making it, and it was so traumatic. I lost 18 percent of my body mass. And it was a nightmare because of my fame. The first doctor just wanted to be on the phone with People magazine, and he wanted to give me exploratory brain surgery. He was crazy and had to be fired.

Horrifying.

Finally, after I bled into my brain for nine days, they did an angiogram and missed the problem — so they decided I was faking it and that it was time for me to go home. I had been on this drug called Dilaudid, which is synthetic heroin, all this time, and was hallucinating, I didn’t know where I was. Eventually my best friend convinced them to try one more angiogram.

When they looked, they realized that my vertebral artery — which, for reference, when Christopher Reeve had his accident, both of his vertebral arteries were ruptured — one of mine was completely ruptured, and I’d been bleeding into my face, head, and spine this entire time. My artery was hanging by a thread. I had to have an eight-, nine-hour surgery. I woke up later with metal coils in my neck and no artery. Then it was a month to see if I would live from this operation, since it was a new type of procedure — which I learned in People magazine when I got home. [Laughs.]

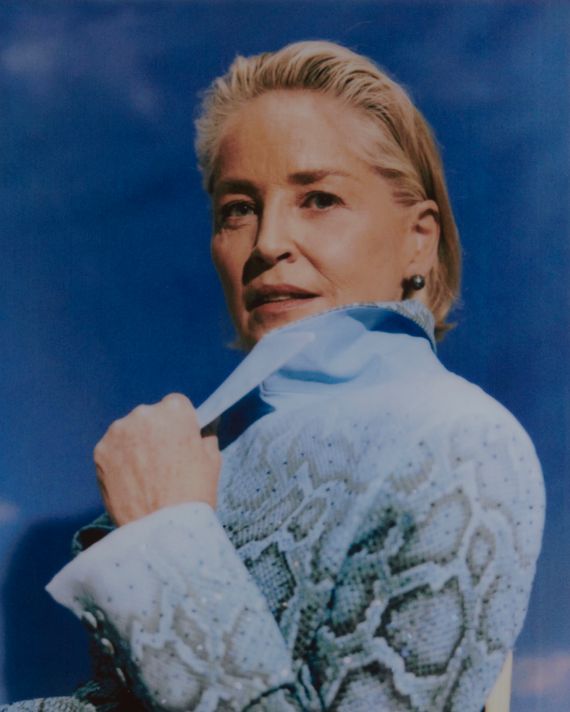

Photo: Chantal Anderson

And the recovery was long and grueling and traumatizing but life transforming.

Yeah. About seven years of recovery. I came home walking on the tops of my feet, no feeling in my left leg, and stuttering and seeing color patterns on the wall. I couldn’t write my name or remember anything. I thought the gardener was a burglar. I just didn’t know anything. My marriage was over.

It ended during this, or it had been ending?

Well it had been ending, but this certainly ended it. This was the end. It was not a great place to try to be recovering. You know how sometimes life gives you taps on the shoulder? “You should probably think about making some changes. You really need to do something different.” And suddenly you find yourself teeth-down in the dirt? It was like that. Like, I wasn’t listening.

So much was being taken away from you so fast —

Everything.

Everything. Which later connects to the name of your first exhibition, “Shedding.”

“Shedding.”

So you were in the carriage with Death and Eternity. You had given up everything and everybody had sort of given up on you.

And I was okay with it.

You were?

Yeah. When I got home from the hospital I couldn’t sleep during the night. I could only sleep during the day. And I kept having these feelings where it was like I was being downloaded with information, but I couldn’t really understand what it was. I just kept saying “I really don’t even know why I’m here. What’s the point? I don’t even know what’s happening or why. But I need someone to protect my son.” I had a 1-year-old child. My husband was filing for divorce, and he and his girlfriend wanted custody. They got it, and along the way disparaged me as a person. I lost my career, I lost my baby, everything. I was in court something like seven times for increased child support, and yet I couldn’t work because of my condition.

You were paying them child support?

Oh yes, and it kept increasing until I had to re-mortgage my house and all my savings were gone, and I was just so up against the wall.

It’s the strangest thing. I was in the Bodhi Tree bookstore in West Hollywood one time before all this happened, and there was a Buddhist statue that was being used as a doorstop. It had a woman holding a vase upside down. And I remember asking the checkout person, “What’s that about? Why is the vase upside down? I don’t get it.” And the person explained, “That’s the absolute moment of complete peace, where you’re at total emptiness.”

Something about that really stuck with me. I recognized that being completely empty doesn’t mean that you’re broken, it can mean that you’re at peace. And then another time I was at my dentist —

There’s a line!

And my dentist is a supercool woman. I had to get a root canal, so she put the shot in my nerve, which caused a seizure — because now I have a seizure condition from the brain damage. When it was over, she was like, “Wow, do you want to go home?” and I was like, “Jesus, no! I’ve already been through all this, please just do it now! Tell me what you’ve been up to lately! Talk to me and get me through all this.” And she started telling me that she and the woman at the desk had been working in a women’s prison that weekend. And I was like, “Oh, so you go up there and do dentistry? That’s so cool.” And she was like, “No, I teach forgiveness.”

I was like, “That’s incredible. Can you do that with me? Can you come over to my house and teach me how to forgive myself? Because I’ve lost everything. I lost custody of my adopted son, which means he’s now lost two mothers, and I don’t know how to live with that.” And so they came to my house and taught me that only God was perfect and it wasn’t about me. What I had to learn to do was be the best mother I could under the circumstances that were given to me, and to not try to make my plan of being a mom how I thought I should be a mother. It really changed my life, this shift to thinking about how to be my best in the circumstances I was in. That’s how I ended up painting.

Photo: Chantal Anderson

I know you always worked as a kid …

I sold Christmas cards and pots and pans door-to-door and mowed people’s lawns and painted barns.

You have identified as “Kitchen Sink Irish.” Can you explain what Kitchen Sink Irish is?

Well, we say there are two kinds of Irish: There’s Lace Curtains and there’s Kitchen Sink. Lace Curtains is high-end Irish. Kitchen Sink is when you have one bathroom and you piss in the kitchen sink when the bathroom’s not available.

You studied art — where did you get your B.A.?

Edinboro University in Pennsylvania. I failed acting in college by the way.

Well that’s encouraging! How did you pick up painting?

I have always drawn and painted. As an adult I would bring crayons and coloring books to set. I remember bringing the Andy Warhol coloring book to set when I was doing Basic Instinct, because you don’t really have much space or downtime on a film set, but it keeps your brain alive.

And then when you were recovering, how did you start painting? Scale-wise, what material, in what room? I think all artists are guided by other voices, that art is using us to reproduce itself somehow.

It is so, so true. My friend sent me an adult paint-by-numbers kit because I said, “I want to start painting again, but I think I’ve lost all my brushstrokes.” Somebody else had given me an easel, and I put it on the easel and I was doing it, and someone took a snapshot of it and I put it on Instagram. And then someone wrote to me and said, “Can we auction it off for charity?” and I was like, “Oh yeah, sure,” and I gave it to them. And Art News took a picture of it for the charity and said “look at those brushstrokes.” And of course, you know, any encouragement and I’m like [pants like a dog].

I love that! “You like me?”

Right, exactly! So I started another paint-by-numbers and I go, “Oh, I don’t have the patience for this,” and I just painted it.

That was the break, right there.

Yeah, where I was like, “I can’t. I’ve just got to paint it.” I finished that and then I thought, Oh, I need to do more to that. So I turned it upside down, I took black paint, and I started painting what looked like Japanese calligraphy down the sides because I thought, That’s what it looks like to me. I wanted it to be this other thing. And then I thought, I’m gonna go over to Blick. I was looking at sketchbooks and the stuff that I would have normally bought, but then I walked into the back and there were these big, pre-stretched canvases. When I went to school we had to stretch our own canvases.

What a pain.

It’s a lot of work. And here there were pre-stretched canvases in the back.

You’re not supposed to use them in the art world, so this is already a major leap.

Right? And I was like, “Oh my God! I can afford a pre-stretched canvas!” And this had never occurred to me because when I was doing this previously, there was no buying that stuff! I mean, come on! Starving actresses don’t buy pre-stretched canvases. So I was standing back there and I thought, I’m gonna buy this 4-by-4-foot canvas, put it in the truck, and take it home!

It sounds amazing and terrifying.

I brought it home and painted it in my bedroom.

When? A week later? A month later?

Oh no, same day. I was like, “I’m just gonna do this! Right now!” I bought an acrylic paint set and some brushes, and I’m like “This is happening!”

Wow.

I started, and I thought, Well, I’m just gonna work on my color field. This all changed with the stroke, because I started seeing colors on the wall and then I got this brain medicine, but I still see extra colors. So I started ordering more canvases. I thought, I am going to paint only these squares and just these color-field paintings until I get it, because this is gonna be my lesson, and I’m gonna do my 10,000 hours. I’m gonna work at this.

That’s the Kitchen Sink Irish again. Work, work, work, work, work.

I have a very large bedroom, so I started doing it in the bedroom, and then before I knew it I was selling my bedroom furniture. I started moving stuff out, I gave away my bed and got this small Parisian-like bed that I shoved to the side, and pretty soon I was just waking up in boxer shorts and a T-shirt, painting all day and all night, getting back in bed, getting up, brushing my teeth, and painting all day, all night. After about ten or 11 months, my kids were like, “This is ridiculous. You have to move out of your bedroom. You don’t eat, you don’t leave your room — this is craziness.”

It sounds possessed — no offense.

I was! I have a guesthouse, so I moved into a bedroom in the guesthouse, and then I literally painted myself into a corner. There were so many paintings. So I sold the furniture in the living-room area of the guest house.

My God!

Then one day I made a painting for a really good friend for her birthday. She’s kind of well-known.

Can I ask who it is?

Her name is Anastasia Soare. She’s Anastasia the eyebrow lady — she didn’t speak a word of English, and then started waxing ladies’ vaginas and eyebrows and built this empire. I’m crazy about her because she’s so hardworking and she made her business out of nothing. We’re great friends because we have the same kind of crazy work ethic.

I made her this 4-by-6-foot painting for her birthday, and we unwrapped it at her party. Afterward I was trying to leave and all these people were like, “We’d like to do a commission!” And I was like, “I don’t know what that is!” They’d ask, “Well, how much are these paintings?” And I was like, “Oh, they’re $30,000,” because I don’t know what paintings are supposed to cost! You know what I mean? They said, “Well how do we get in touch with you?” I was like, “I have to go!” I didn’t have any idea what I was supposed to say or do, and I just thought, Bye!

Classic artist answers.

Right? And, about eight days later, I got offered a show.

Bam!

And I was just like, “A show? How do you do that? What do you do?” I didn’t really have any understanding. I’m still kind of winging it.

We’re all always learning in public, and especially as an artist, you’re making it up as you go. What is your process? How many paintings do you have going at once?

It just really depends. It can be anywhere from one to eight or nine.

Okay, so you’ve got a lot going on. Do you have a drawing practice?

For more figurative things, I do, but it depends on the painting. There’s a point where you just listen to yourself and paint.

You get out of your own way.

You just paint. I think this is why I work so well with Paul Verhoeven, who directed Basic Instinct. That’s the thing he said to me when I was terrified, since I was the 13th person they offered the movie to. Even when we were shooting, I thought, Oh, they’re just waiting for Michelle Pfeiffer to change her mind. They don’t really want me. He came up to me one day and said, “You know, there’s an angel that flies through you. Just get out of the way.”

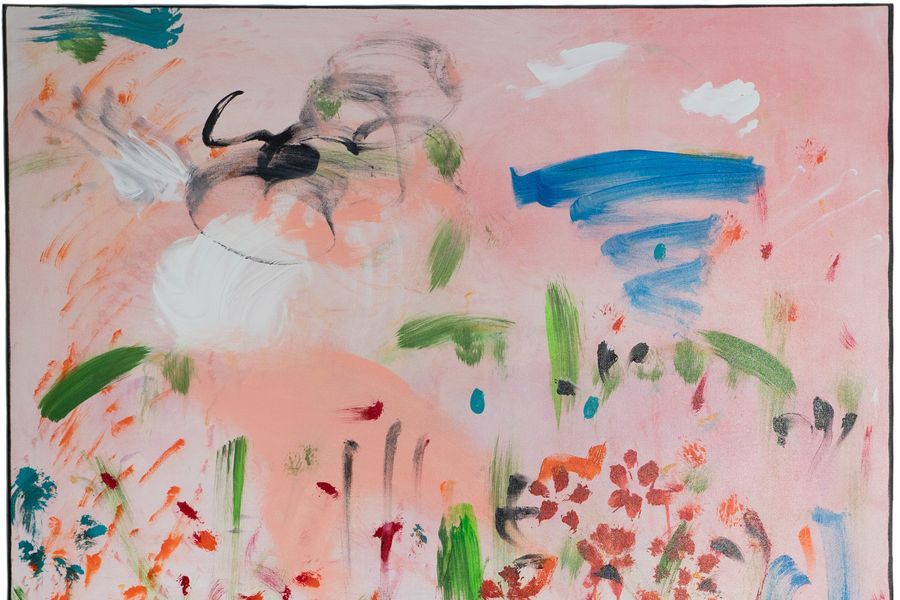

Let’s look at some of your work. I want to talk about the title of this painting. When was this painted?

This was painted in ’22. It’s called It’s My Garden, Asshole.

It’s My Garden, Asshole

Art: Sharon Stone

Tell me about the title.

I had this really dear, dear friend. She was over 40, she was trying to have a baby with her husband, and she lost the baby. It was really hard. I’ve been there, and I’m sure many women in this room have been there. It’s the unspoken thing. Then she got pregnant and she was able to carry the baby through, but she was in her mid-40s and she gained a lot of weight. Not the L.A. kind of pregnancy, right? She had a regular pregnancy, gained the regular amount of weight, and had the most beautiful baby ever. Her in-laws came to visit, meet the baby, and they all went out to dinner to have pizza and celebrate the baby, and her father-in-law said, “You know, you really shouldn’t be eating that. Look at you!”

Unbelievable.

And she called me and she was just so broken, because she was so hormonal and upset. And I said, “You know what? It’s your garden, and that asshole doesn’t get an opinion.”

Boom!

“Because you gave him the greatest gift you could ever give, right? You did the greatest thing you can ever do, and you did it past your shelf life!” And it made me so mad, so I named the painting It’s My Garden, Asshole.

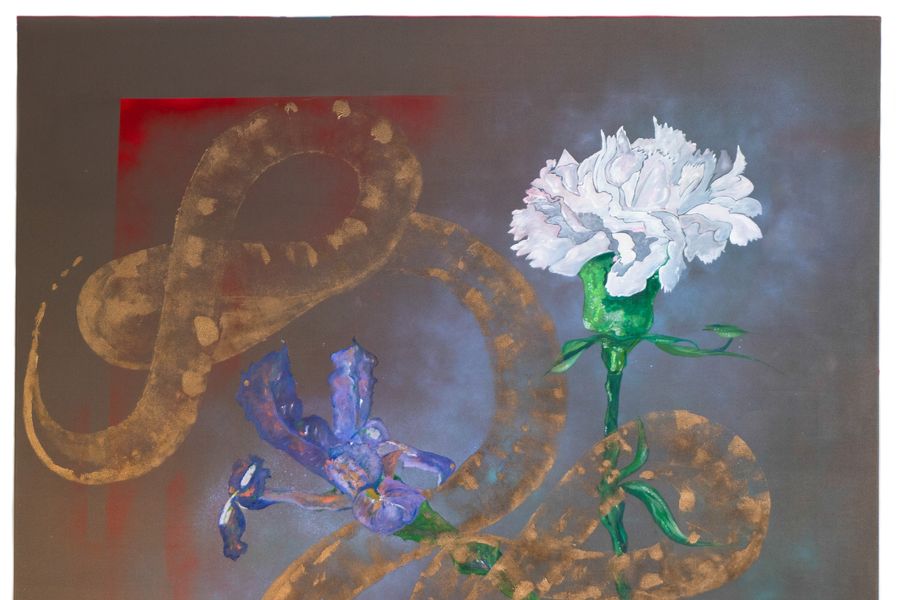

Welcome to My Garden

Art: Sharon Stone

I want to dwell on the idea of It’s My Garden. What is the word “garden” to you? Because you use it in a few titles, and “Welcome to My Garden” is the name of your exhibition in Greenwich, Connecticut. Here’s a painting with the same name.

Well, in the beginning, we thought that God was nature. The moon, the sun, the water, the Earth. And we loved God in this way. And then when Man decided that he wanted the land, the water, the Earth, everybody chose these various religions in order to speak to God and threw God up in the sky and then created all these borders and boundaries that became identity. “You are Canadian, you are Indian, you are Chinese, you are American, you are French, and God is up in the sky.” But prior to that, we were just human beings who loved nature, and God was in nature. The garden is where God lives, in nature, and in the end, nature is going to make all the decisions. You don’t have to believe in climate change, just as gravity doesn’t require your belief. Climate change is gonna occur with or without you. So that’s sort of how I think about the garden thing.

These are not totally realistic or totally abstract. There’s a flower in it and shapes and colors and …

Yeah, these are never the whole snake. There’s no head or tail. Snakes are the only animal that sheds its skin constantly. What I like about that is that it’s the one that changes and grows and just keeps shedding as it continues to change and grow. So I put this shape in a lot of my paintings because it’s very interesting to me that this is about changing and growing.

And then there’s a kind of change of mood where you get like, a Chinese kind of landscape, like in Bayou. What year is that?

2021.

Bayou

Art: Sharon Stone

And how is the tree made?

This is acrylic, but it’s also spray paint.

I thought so.

I’m starting to use spray paint to express this impressionistic perspective.

Giverny

Art: Sharon Stone

Giverny. Can you pronounce it?

“Guh-vur-nee.” I have these friends whose family legacy is to take care of these giant, important estates. They took care of Versailles, and I got to go there when it was closed. They were taking care of Giverny, which is where Monet painted the beautiful Water Lilies. They had a child who was about 6 or 7, and I said to their kid, “Will you take me everywhere and show me where all the paintings were painted?” We got to go up in the rooms and look through the porch boxes, and we got to crawl around on the bridges and pull away the brush. “Oh, this is where the rowboat was painted from, and this is where this painting was painted from.” We got to crawl around in the grass and see where Monet painted all the paintings. This was my impression of my day with this 6-year-old there, which was just thrilling.

Dreamscape 1

Art: Sharon Stone

This is Dreamscape 1.

This is just the way dreams look to me sometimes.

River

Art: Sharon Stone

I think your more recent work has taken a real turn, and I’d like to say I’m noticing it in this one. I wonder if you would talk about River.

My 11-month-old nephew and godson died of sudden infant crib death, and his name was River. I painted this for him. Where do you go? What’s it like? As a person I’ve always felt … odd. I felt like there were other solar systems, and that I was from one of those other places. It looks more like this where I’m from, and that that’s where he was going.

The Party

Art: Sharon Stone

What’s going on in The Party, and when was it painted?

This I painted a while ago. It’s similar to the one I painted for Anastasia, except she was Romanian so I painted the floating balls at her party in the darker colors from Romania. And I painted this because I just felt like this was like a Hollywood party.

Is that what they’re like?

Yeah. [Laughter.]

Unpinned

Art: Sharon Stone

This one, Unpinned, is a real beauty. When was this made? The shape in the center appears to kind of hold the whole thing together or blow it apart, or to be a body? What’s going on here?

I just painted this. I started making these more graphic underpaintings, because now I paint at different stages. I paint an underpainting, then sometimes a middle painting, and then the painting painting, because now I understand what I didn’t understand when I started, which is that there isn’t just “the painting.”

Artists, do you hear that? “There’s not just ‘the painting.’”

The painting comes in stages, in levels and layers. Sometimes it happens where the painting just comes. But sometimes, you’re painting and you recognize, Oh, this is the underpainting. And then you paint again, and you realize, This is the structural piece that’s going to hold the ultimate painting. So this had an underpainting, this had the graphic piece that was the structured piece, and then it had the butterfly. And then in the end I was like, “I want to do the body in the middle,” which I drew in pencil.

You wear a lot of hats. You do not stay in your own lane.

Well I was told in the beginning of my career, when I wanted to write a book and do other things, “Stay in your lane.” I wanted to write a book of short stories. “You can’t do that! You can only do a memoir.” But I’d written a bunch of short stories for different magazines, so eventually I was like, “Well, I’ll just turn my short stories into a memoir and lace them together!” But yes, it was always, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that.”

What do you want to tell everybody?

You can do whatever the fuck you want! And all you have to do is do it. It requires discipline. And what you have to do is you have to have discipline. People start things, but they don’t finish them. You have to finish it, and then demonstrate your completion of it. That’s a whole thing. So it’s not just that you can do it, you have to do it and finish it, and then continue your discipline. Discipline is everything.

Everything.

Discipline is freedom. I don’t care whether you’re working out or having a friendship. It’s discipline. If you think, Geez, why haven’t I heard from my friend? Well, has your friend heard from you?

Photo: Chantal Anderson

It’s difficult for creative people who have become famous for other things to cross over into the art world. Have you run into that?

Well, most people don’t want to take me seriously. They have that troubling vagina problem. And if you’re attractive, again, you must be an idiot.

Or you slept your way there and all of that.

You can only sleep your way to the middle, so forget that. But I would say that great success makes people think that you don’t have any talent. If you’re “pretty successful,” you’re probably considered to be talented. But if you’re “greatly successful,” your talent will always be in question.

And if you’re a woman and you’re greatly all of that, then what are you?

Fucked.