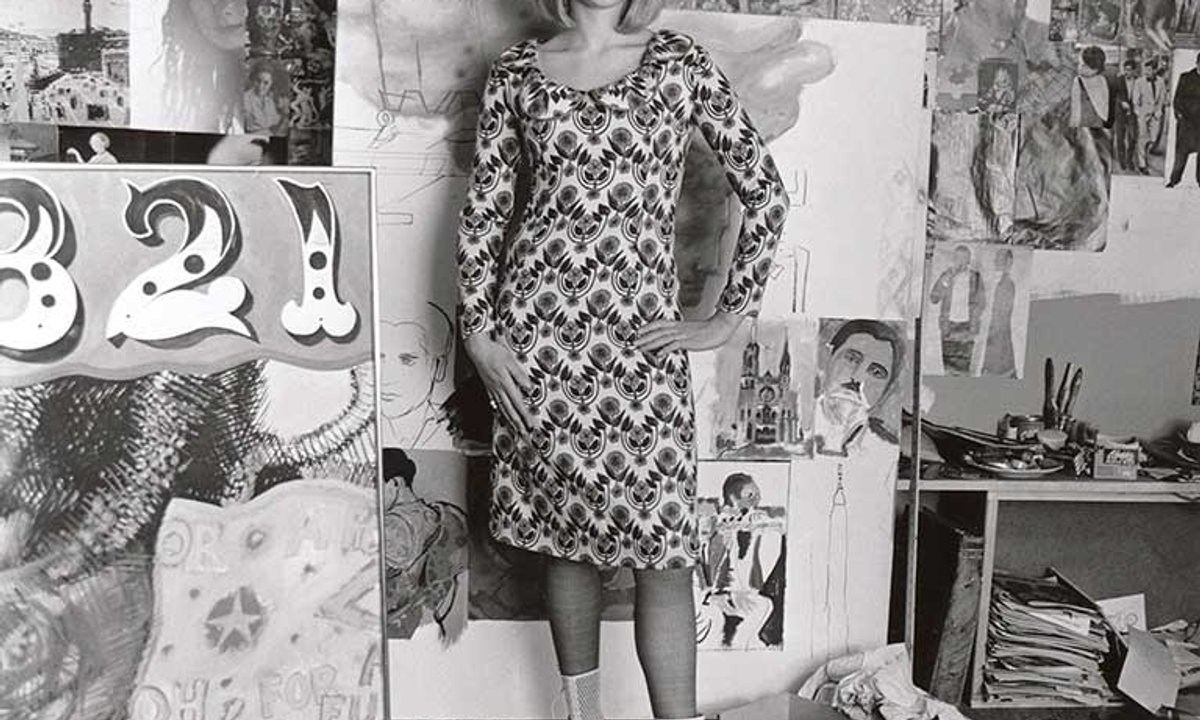

Pauline Boty, one of the founders of Pop art who died tragically early at the age of 28, has gone down in art world folklore as one of British art’s unsung heroes. But Boty is now undergoing a renaissance, most recently with an exhibition at the Gazelli Art House in London (until 24 February) and a new book, Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister, by the author and screenwriter Marc Kristal, highlighting the artist’s legacy and contribution to post-war British art.

Although Boty was in key shows, including the very first Pop art exhibition at the AIA Gallery in London in 1961, her work disappeared from view for almost 30 years. Having been diagnosed with cancer after a pregnancy check-up, Boty was offered an abortion so she could have radiotherapy, but turned down both. She died in July 1966, her daughter not five months old. An artist herself, the daughter, Boty Goodwin, overdosed and died the night after her graduation from the California Institute of the Arts.

In the early 1990s, the curator and art historian David Alan Mellor rediscovered important works by Boty in a barn on her brother’s farm. He went on to restore and exhibit them at the Barbican in London in 1993. Since then, interest in Boty’s work has slowly gained momentum; in his book, Kristal puts the Pop artist back in the spotlight once again.

Kristal says: “Boty’s contribution to the history of British Pop art is singular and significant, and for many years after her death, both she and her work lapsed into obscurity. Her paintings and collages were rarely exhibited, and the artist was remembered, if at all, as a tragic figure whose promise went mostly unfulfilled. By looking in depth at her life and times, the book reveals an individual who was at once central to her historic moment and a figure of importance to the present day.”

The writer’s interest in Boty was sparked in 2013 when, to escape the London rain, he wandered into an exhibition at Christie’s auction house called When Britain Went Pop. A painting in the show by Boty, It’s A Man’s World I (1964), stopped him in his tracks. The work comprises archival pictures of historic figures such as Albert Einstein, Marcel Proust and Vladimir Lenin, along with an image of the assassination of John F. Kennedy based on frame 308 of the home movie shot by Abraham Zapruder.

“It was the first time I had seen any of Boty’s work, the first I’d heard of her, and I was struck by the power of the painting, its simultaneous celebration and condemnation of ‘a man’s world’—a work at once light-hearted and pitiless,” Kristal says. “It reminded me of [the novelist] F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that genius is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in one’s mind simultaneously. Moreover, I felt very strongly the personality of the artist. I wanted to know more, and that’s how I began the journey that led to the book.”

Chapters cover Boty’s time at London’s Royal College of Art (RCA), between 1958 and 1961, where she studied stained glass design following a stint at Wimbledon School of Art. “Learning about the Royal College of Art in its fervent post-war years was illuminating and enviable—how I wished that I’d been there,” Kristal says. “As for the most interesting discovery, that’s hard to say, because there were so many. But without question, the best part of it all was living with this woman in my mind for a decade, and being profoundly inspired by her example.”

Pretty tough

Kristal draws on first-hand testimonies from friends and colleagues, who vividly paint how Boty blazed a trail at the RCA. “She was quite masculine in the way she behaved,” observes the fashion designer Celia Birtwell in the book. “Nothing cosy about Pauline … But I wouldn’t describe her as super-worried about anybody else. She had that drive for herself. Although she looked incredibly pretty, Pauline was quite tough.”

There are plenty of tales reflecting Boty’s resilience and ambition in an environment dominated by men. Her fellow student Geoffrey Reeve points out that Boty “was producing a huge amount of work [at the college]. She was one of the boys, really.”

But Kristal aims to counteract the popular image of Boty as an all-conquering proto-feminist. “It’s a mistake to assume that Pauline Boty’s life was without inner as well as outer conflict,” he says. “Something one sees again and again is the difference between what she put into the world and what the world chose to make of it. Yet while it’s true that Boty struggled against the prevailing notions of what a woman could do, and what a woman could be, she was also the middle-class daughter of a suburban accountant with exceedingly traditional values and expectations, and I believe Boty had to do battle with those impulses within herself as well.”

Crucially, Kristal claims to debunk a few myths that have built up around Boty. “It was quite an adventure, discovering all of the misconceptions about Boty, as regards her artworks, her acting career and her life. Maybe the most startling was that her most famous painting, The Only Blonde in the World (1963), was actually finished before Marilyn Monroe’s death rather than after, as is commonly assumed.” As she had been largely overlooked, and no one had dug deeply into her story, the myths and legends surrounding Boty had ossified into what seemed to be fact, he says.

One of Boty’s most famous works is The Only Blonde in the World (1963)

Estate of Pauline Boty

So is Boty still underrated? “She has gone, in the space of a generation and a half, from being someone who was regarded by certain critics as a bad, derivative painter whose reputation rested on her looks and personality to being heralded as a forgotten genius,” Kristal says. “I am only glad that, at long last, Pauline Boty is back—hopefully, this time, for good.”

• Marc Kristal, Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister, Frances Lincoln, 256pp, £25 (hb)

• Pauline Boty: A Portrait, Gazelli Art House, London, until 24 February