“This is very depressing, and it hurts,” writes Chinese artist Xiyadie, of living in a still “largely traditional sociocultural environment” as a gay man. Xiyadie, a pseudonym translating as Siberian Butterfly, documents through traditional-style papercuts his closeted life in mainland China’s rural, conservative north east before migrating to Beijing.

In the second chapter of new anthology Contemporary Queer Chinese Art, Xiyadie traces in parallel his entrance into Beijing’s burgeoning LGBTQ community of the early 2000s and his emergence as an artist, first through inclusion in the seminal 2009 exhibition Difference-Gender and then a solo show the following year at the Beijing LGBT Centre.

Over 15 chapters by 16 contributors, editors Hongwei Bao, Diyi Mergenthaler and Jamie J. Zhao present the emergence of LGBTQ+ art in China since the mid-1980s. An overall hopeful narrative of forging creative and social spaces is shadowed by how invisible queer art remains in China’s mainstream, increasingly commercialised art scene, and Chinese society’s shrinking space for alternate discourses since the mid-2010s. For queer artists and their supporters, we have come so far, have so far still to go, and have so much to lose.

Billed as the first English-language, intersectionally academic book on the subject, Contemporary Queer Chinese Art adds a broad and analytical scope to a tiny bookshelf of exhibition catalogues and magazine articles about queer Chinese artists. Its inclusion of overlapping feminist Chinese art, if incomplete, fleshes out the context of a parallel patriarchal taboo. While gay Chinese artists born after 1990 are increasingly open about their identities, far more remain closeted; and recently even deliberately queer-focused exhibitions are evasive in how they present, to avoid tightening censorship. Queerness is among the subjects that mainland institutions routinely self-censor, a “Don’t say gay” policy that even straightwashes Andy Warhol. This book’s spotlight, and documentation of a fragmented history, is a precious contribution.

Xiyadie’s narrative, along with other straightforward artists’ essays, form some of Contemporary Queer Chinese Art’s strongest segments particularly when relating own experiences as different generations of LGBTQ mainland and expatriate Chinese. “It is true that the concept of homosexuality has gradually entered people’s consciousness” in China, writes Si Han, the curator of the 2012 Secret Love: Chinese Homosexual Artists Exhibit show at Sweden’s Ostasiatiska Museet. “But there are great differences between rural areas and large cities, between older and younger generations and between different social classes and levels of education.” While the chapters by and about artists like Xiyadie and the gender-bending Ma Liuming provide older and rural migrant perspectives, even their stories converge in Beijing.

The book provides an accessible introduction to non-Chinese readers through extensive footnotes, explainers and English-Chinese glossaries. They explain evolving slang, how tongzhi (comrade), ku’er (queer), lala (lesbian) and kuaxingbie (transgender) have replaced the formal tongxinglian (homosexual) in the lexicon. Less cleanly spelled out is the history, which is sprinkled throughout chapters, particularly those by Shi Tou, a lesbian artist and activist since the early 1990s, and activist performance artist Wei Tingting, whose arrest as one of the famous “Feminist Five” in March 2015 presaged the current clampdown.

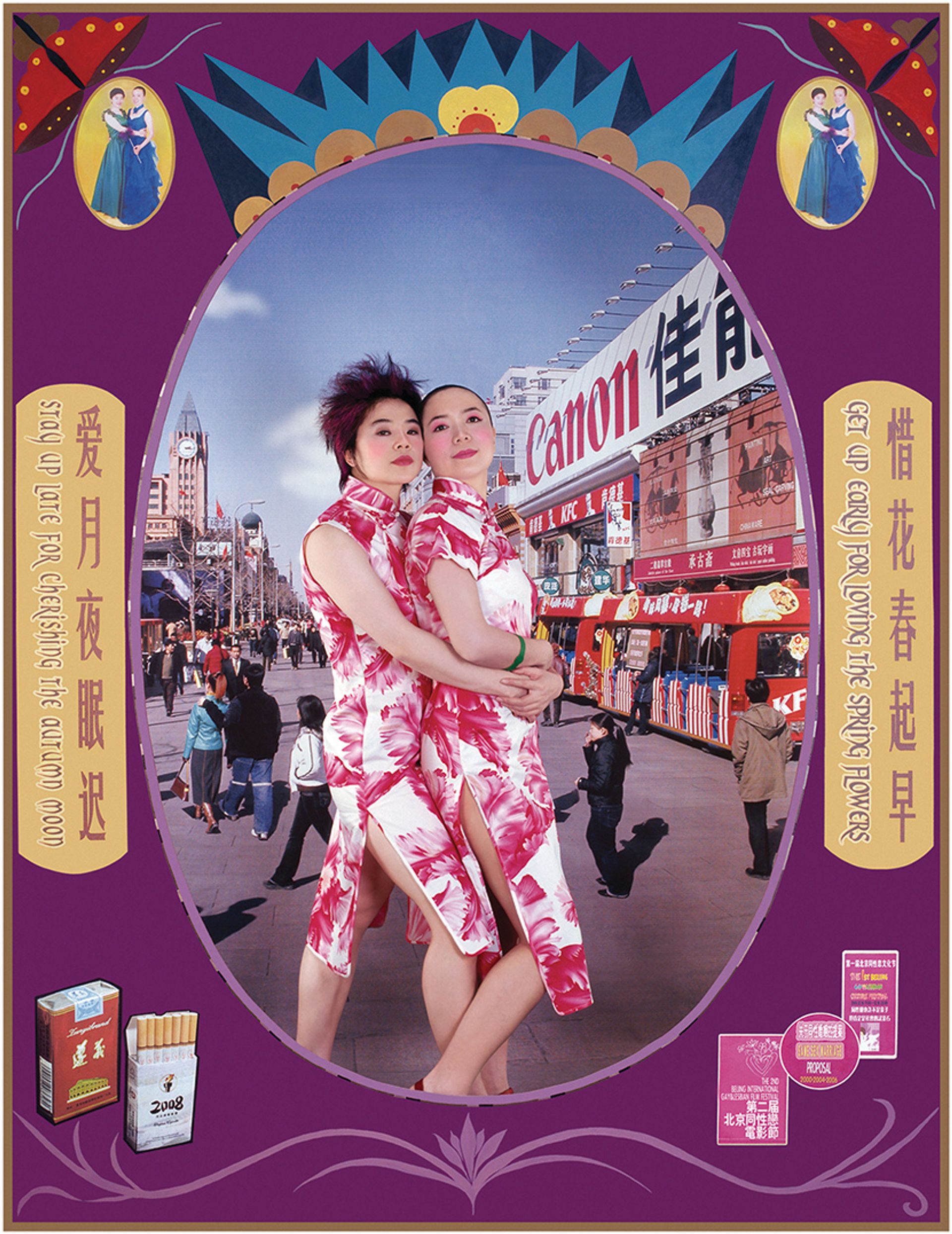

Commemorate (2006) by Shi Tou. While China legalised gay sex in 1997 and declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder in 2001, growing censorship in recent years is impacting both on how LGBTQ+ artists present themselves and how curators angle those artists’ shows Courtesy of Shi Tou

Both Queer and feminist art emerged in the heady 1980s, with Xiao Lu’s 1989 “Dialogue” still a resounding feminist statement. China’s first all-women contemporary art show, The Female Artists’ World, was held in May 1990 at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts. Active in Beijing’s East Village since 1993, Ma Liuming was arrested for his gender-bending performance art in 1994. In 1995, the United Nations World Conference on Women was held in Beijing, sparking both feminist and queer discourse, although records were erased about its lesbian tent, as Wei Tingting discovered when researching her 2015 documentary, We Are Here.

Queer artists like Shi Tou were among those expelled in October 1995 from the lively Yuanmingyuan artist community. In 1996, Beijing’s Aizhixing Project began advocating for gay rights, while Zhang Yuan’s film East Palace, West Palace, about Beijing cruising, launched an era of queer Chinese cinema. China officially decrimnalised gay sex in 1997; previously it had been part of a vague swatch of non-comformist offences also including heterosexual premarital sex and gender non-comformity labelled “hooliganism” (liumangzui).

The next year, Shi Tou organised the first Chinese lesbian conference and founded the group Beijing Sister, which ran a lesbian hotline and published the lesbian magazine Sky (Tiankong). That March saw another influential all-women exhibition, Century Women, during which artists Cui Xiuwen, YuanYaomin, Li Hong and Feng Jiali co-founded the feminist collective Sirens Art Studio.

In April 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder, launching hopes of fuller acceptance. That year, the filmmaker Cui Zi’en launched the Beijing Queer Film Festival. Its subsequent director, Fan Popo, contributes a personal essay to the book tying efforts to keep his 2012 film Mama Rainbow available on the Chinese internet to cultural alienation following his emigration to Berlin. The film tells the story of six Chinese mothers who have accepted their gay and lesbian children.

The Beijing LGBT Centre was founded in 2008, while in 2009 Beijing’s Songzhuang artist community held China’s first LGBTQ exhibition, Difference-Gender. Reflecting the times, state media China Daily reported enthusiastically on it and the just-launched Shanghai Pride Festival, declaring it the “Year of Gay China”. Shanghai Pride persisted until 2020, when its directors were pressured to suspend activities.

The Ostasiatiska Museet 2012 show Secret Love, featuring almost 30 artists including Ren Hang, Chi Peng, Ma Liuming and Shi Tou, first brought international attention to queer Chinese artists. In 2014, Beijing gay club Destination hosted Conditions: An Exhibition of Queer Art, whose curator Li Qi would go on work at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum, organising a Felix Gonzalez-Torres show in 2016.

Sunpride Foundation, established by Patrick Sun, a collector originally from Hong Kong, to promote LGBTQ+ Asian art, held its first Spectrosynthesis show in Taipei in 2017, as Taiwan was poised to be the first place in Asia to legalise same-sex marriage. While written before Spectrosynthesis’s acclaimed third edition in Hong Kong from late 2022, the book also skips its more pan-Asian 2019 Thailand exhibition in favour of its inaugural edition, which exclusively featured ethnic Chinese artists.

Space for such scholarship and activism continues to shrink within China, but Jiete Li and Claire Ruo Fan Ping write about how, in 2020, seven Chinese women living abroad created the Banying platform (translated as In Light of Shadows), which launched a popular podcast and in March 2021 organised the Women’s Art Festival in Beijing. Involving established artists like Xing Danwen, Bingyi Huang and Wen Hui, and the curator and art historian Carol Yinghua Lu, it attracted 1,100 visitors and 500,000 online views. Even from exile, the fight continues.

Hongwei Bao, Diyi Mergenthaler, Jamie J. Zhao (eds), Contemporary Queer Chinese Art, Bloomsbury Publishing,a 248pp, 50 colour illustrations, £85 (hb), published 13 July

• Lisa Movius is a writer based in Shanghai, and China bureau chief, The Art Newspaper