By KEVIN FITZPATRICK

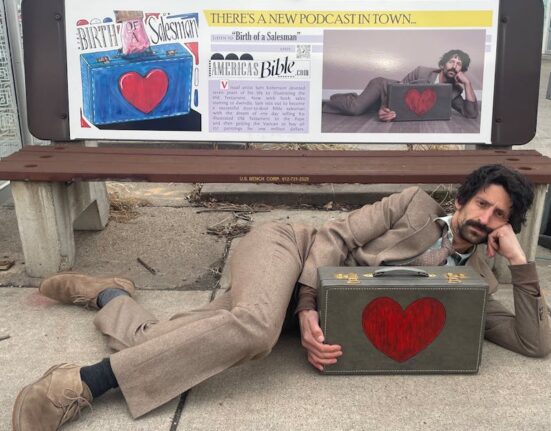

I first met Nilton Cardenas on Nov. 8, at the opening of an exhibition he organized at the Cranston Public Library, titled “Lines of Feeling/Lineas de Sentimento.”

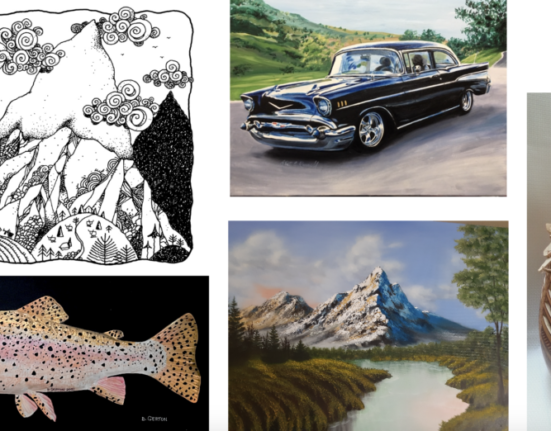

Twenty-one black and white drawings by six artists hung on display, all created in the preceding several months, all based on a somewhat nebulous theme: to “seek answers and pose questions that are inherent to their nature.” The drawings were done in a variety of styles and mediums, the only obvious connection being the monochromatic palette, and a somberness which spoke of melancholy, bad memories, and anxiety.

Despite that somberness, Nilton bounced around the room radiating pride in the gallery and in the artists. At the beginning of the night, Nilton gave a speech, explaining the inspiration for the exhibition. He described a time in his life when three loved ones passed away, and he chose to abandon color in his practice, electing instead to adopt a black and white palette for his next series of paintings.

He asked, “How I can express my deepest sadness, my emptiness, my solitude?”

As he described this grief, Nilton was dressed in bright pink and blue. Easter colors, as if to say that though the artworks we see today stem from grief, the sharing of that grief is cause to celebrate.

Nilton went on to describe a simpler inspiration which, I would come to understand as I got to know him better, is not only a theme for this gallery but for the man’s entire life’s work. He wanted to afford these artists, who for one reason or another hadn’t had many chances to put their art out for the world to see, an opportunity to share.

Most of these artists had never met until a couple months before the opening of the exhibition. They were Nilton’s friends or colleagues or students. At least one artist, Niko Tolentino, Nilton himself had only just met by chance when the artist was painting a mural as Nilton happened to be passing by. This was enough to warrant an invitation.

“When I say ‘I’m an artist’ often they say ‘I’m an artist too.’” Nilton said in his speech. “When I talk with an artist, always I say ‘Show me your work! Show me your work!’ and some people, they show me their work. And I ask, ‘Do you have any shows? Do you present any gallery?’ No! I save it. I hide it! Don’t do that. We need you as an artist.”

Nilton asked each of the artists to speak to the audience about their work, which each of them did, with varying degrees of comfort. Later on, I had the opportunity to speak with a few of the artists, Michaela Clift, Linda Peterson, and Kyle Dumkuski, as a group. In my interview, they all spoke so eloquently not only about their own work, but about each other’s work. They had developed a rich understanding of one another as artists, despite most of them having only met a few weeks prior. They had been empowered to take a very personal stock in the gallery and the other artists.

This was by design. Nilton described to me later how each of them helped in some way in the creation of the gallery, so that each of them could take personal pride not only in their individual creations, but that of the collective. This is because Nilton’s priority in all things is not to simply create art or exhibitions or even to elevate individual artists, but to build communities. It is a skill he came by honestly.

Nilton comes from Peru, where he lived with his family and attended art school until, facing the threat of political violence, his father chose to move the family to the United States. When Nilton was in his early 20’s, the family moved to Miami, Florida, and then eventually to Providence. It was there that Nilton would take part in his first exhibition, a Latino Art Exhibit at the University of Rhode Island.

At the same time, Nilton’s father was becoming an institution in Rhode Island.

Nilton’s Father Jorge F. Cardenas was a community leader, and an advocate for the Latinx community. He spearheaded many campaigns and projects designed to uplift the people of Rhode Island. Nilton spoke glowingly about the Back to School Celebration, a program founded by his father, which for over 20 years has distributed tens of thousands of backpacks and other school supplies to children across Rhode Island. After his death in 2020, Gov. Dan McKee was among his mourners, and a street in Central Falls is now named after him. It is his father’s spirit of community leadership that Nilton applies to everything he does.

“I used all my skills to help my father,” he said. “But in the same way I learned from him, ‘How is the community leader presented to the community? How is the leader acting to the community? How the leader compromises himself to the community.”

Nilton’s career is threefold. He is an artist, a teacher, and a community leader. He is an accomplished painter who has exhibited work across the state, country, and internationally. He has received dozens of awards, certificates of appreciation, and citations for his work as a community leader. He is a teacher in public schools, after school programs, and camps. He is a member of the Cranston Arts Council. But all these diverse accomplishments all seem to come from the same fundamental passion, and the scale of the project seems irrelevant to his enthusiasm for it.

When I asked about Nilton’s inspirations, he brought up Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueirios, Jackson Pollock, Rembrandt, and Roberto Matta — artists known for (among other things) working at huge scales, on the sides of buildings or canvases the size of entire rooms. Certainly, Nilton works at that size.

But as of writing, I have only seen one of Nilton’s pieces in person. I meant to go see some of his local murals, but I caught a cold over the weekend and couldn’t make the trip. So I have only seen a single pen and ink illustration, about the size of a dinner plate and hung in a corner of the gallery at the Lines of Feelings Exhibition, which the other artists had to convince him to add to the gallery so that he would have work to share up on the wall with the rest of the team.

Titled “The Girl,” it depicts a swaddled figure in a straw hat and braids cradled in a woven contraption of wooden beams, wicker, and dried leaves — a little Andean child supported by a fragile framework, half grown organically, half carefully constructed.

There’s something archetypical about Nilton. It’s hard to describe, but I think what I mean is this. If there were only 10 people in the whole world, Nilton would be one of them. He is filled with an enthusiasm and pride that is somehow devoid of ego, despite all his accomplishments. He knows what he does is vital, but even when given the chance to talk about himself, he would prefer to talk about the other wonderful people in his life. There’s just a simple certainty in the value of his actions, and by extension in the actions of everyone he meets. It says “I am a person in this world, and therefore I will act.” I’m glad that he does.