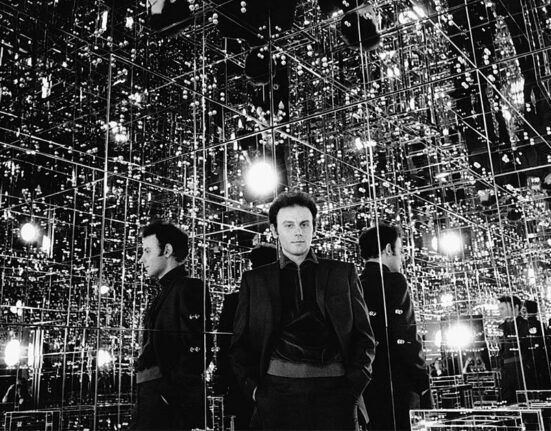

Matthews, Rashawn Ross and Jeff Coffin perform at Madison Square Garden on Nov. 17, 2023, in New York City. Dave Matthews Band was one of the earliest adopters pushing for sustainability via riders.

Photo by Taylor Hill / Getty Images / ABA

Artist riders have a certain reputation.

Ask the man on the Clapham omnibus and he’s likely to describe a degenerate catalog of stereotypical rock ’n’ roll excess and/or an inscrutable, hyperspecific list of diva-assuaging demands.

There are plenty of attested examples of both. Tales of crates of hard liquor or dressing rooms that must be set to precise temperatures. M&M’s sorted by color. Four throw pillows, each of a certain color, on the sofa.

The vision is always some caricature that’s of Spinal Tap and Miss Piggy on their worst days.

It’s the nature of storytelling and memory that the most absurdist examples persist, but the vast majority of riders are far more mundane than all that. Performers thrive on routine and, besides, why not indulge in a little silly excess if you’ve earned it?

At their core, riders are ways for artists to demonstrate preference.

Increasingly, that preference goes beyond bottled water brands and HVAC settings. If artists themselves are brands, then they can use that brand to advance causes they care about.

Enter the green rider. Venues have developed them — The O2 in London is proud of its version — and the major agencies have developed boilerplate versions in concert with leading sustainability organizations.

Denise Melanson is Wasserman’s Senior Director of Social Impact, and she and her team, in partnership with artists, venues and other stakeholders, have developed the agency’s green rider.

It’s a four-page list that covers everything from single-use plastics (to be avoided) to food (sustainably and locally sourced) to vehicles (electric or hybrid runner vehicles and no idling from fossil fuel-powered trucks). There’s instructions about the disposal of leftover food, which is to go to staff, crew or homeless shelters or to compost. It’s comprehensive and with the right balance of flexibility and rigidity.

Melanson points to Wasserman client Dave Matthews Band as a pioneer in the green rider movement. And then there’s Guster, whose guitarist and vocalist Adam Gardner founded REVERB, which engages musicians and fans on environmental issues, with his wife Lauren Sullivan. Melanson says it makes sense that the charge would start with heavy touring, road warrior acts.

“It really takes a musical artist who’s on the road every day to identify what is needed and what needs to be changed. We consulted with all kinds of folks in putting it together. Before I did this, I was an agent, so some things I know, but times change, things evolve and you really do have to listen,” she says.

Green rider is an opt-in for Wasserman clients, and Melanson says it can also be a la carte — some bands may only want to focus on the vegan food sourcing, for example — but most everyone is receptive to it when given the option.

“Sometimes they don’t think about it until it’s presented to them … I really believe people want to do the right thing and want to do the good thing but they just need a little direction, a little hand holding,” she says.

There is a cost associated with meeting the green rider. Organic food is more expensive than off-the-rack food. Alternative energy sources are often more expensive than fossil fuels. Emerging artists might find it tougher to ask for the greener, but pricier choice, whereas megastars like Coldplay and Billie Eilish have the clout (and grosses) to make those sorts of demands.

But as the sustainability movement grows, venues of all sizes have adopted their own sustainability policies, making fulfilling the rider easier.

“This is the cost of doing business and some of that stuff you start to get it at scale and the expansion of vendors is making it more competitive where things are not as expensive, so the more that this is growing as an industry, it’s easier for venues to access,” Melanson says.

Ultimately, it’s about making sure artists know they have the ability to affect change, Melanson says, even through something as prosaic as a rider.

“They understand that they have the power to make the right asks.”