Mina Loy, installation view of “Strangeness Is Inevitable,” the Arts Club of Chicago, 2024/Photo: Michael Tropea

Mina Loy, the underknown artist, poet, inventor and maker of otherworldly lamps, was once in love with a boxer. Loy’s second husband, Arthur Cravan, was called the “prizefighter poet.” Though their time together was marked by poverty and struggle, both artists were creatively stimulated by each other. Loy scholars reference her unpublished autobiography “Colossus” (dated around the early 1920s), a term of endearment she had for Cravan, to assert that she not only considered him the love of her life but also that the world of boxing influenced her own poetry and writings. In popular imagination, the story ends with Cravan’s disappearance at sea. Loy had their first child alone. Cravan’s body was never found.

What I write above could be considered both misogynistic and lazy. I introduce a formidable artist and staunch advocate for women’s rights through her male lover’s sphere of influence. On the paragraph’s surface, it’s a failure of the Bechdel Test in all its permutations. Yet, just like Loy’s relationship to boxing, the weave of her text, the staccato dance of her language, my mention of Cravan is a feint, a duck and dodge, to turn you toward a contemporary author: Katherine Dunn.

“Like all things human, boxing is complicated and full of contradictions. Whenever you get to thinking you know it all something smacks your ear to refresh your humility.” —Katherine Dunn, from “School of Hard Knocks” in “One Ring Circus: Dispatches from the World of Boxing”

Loy and Dunn share a certain inscrutability as artists. This, this sentence, is where I wanted to take you. Look at it, feel its fluff, its cotton-candy nothingness. I hate the word inscrutable, I hate inscrutable’s watered down, half-smiled mystery. I hate that Dunn’s life, her teenage stint in jail for selling magazine subscriptions, the dense yearning decadence of her carnivalesque masterpiece, and her turn to boxing—her fierce knowledge on the sport—are reduced to a single, limp word. I hate that Loy’s own retrospective, “Strangeness is Inevitable,” at the Arts Club of Chicago—containing over eighty of her paintings, drawings and constructions—and the first monographic presentation of a fascinating and utterly unique artist, is a paean to her inscrutable creativity.

Mina Loy, “Devant le miroir,” ca.1905, graphite on brown paper mounted on cardboard, 16″ × 13″. Private collection/Photo: Jay York

DING, DING, DING!

This is not a text on boxing, on Arthur Cravan, or Katherine Dunn; but rather a dance, a rumination, a punch in the face, a constantly running question, on how to talk about Mina Loy. My diatribe against the reception of Loy’s work is not directed at the Arts Club, nor at curator Jennifer Gross’ herculean effort to unite the many tentacled making of Loy’s robust life but, rather, how we think about this life.

In our reception of female artists, especially those who identified as or created within Surrealist, Modernist and Dadaist circles, we tend to flatten their lives under the weight of modern musedom. We must always repair, reconsider and re-evaluate the impossible contours of life before moving on to the next big thing. Muses don’t last long at the market. The muse’s glamor and her wretchedness are artificially sanitized, chopped up, and sold for parts. It’s hard to be terrible, it’s hard to be ecstatic, it’s hard to inspire, it’s hard to be inspired, it’s hard to be someone, something, so incredibly outside of the familiar that language cannot hold you. Loy’s only novel, “Insel,” published in 2014 through Melville House’s Neversink imprint, is both a story of 1930s Parisian bohemia and a parable of the creative process itself. To create can both ruin and save your life, because to create is to love something, whether it be words, the freedoms of graphite and gouache, or the halo of light that radiates outward from the lamp you made.

This sense, this feeling of love is what I want, and what I want to give to you, in writing, talking, and thinking about Mina Loy. I will fail in this endeavor. The fissures of failure have already begun to crack and seep through these paragraphs. Language is forever insufficient to capture and calcify the love that girds creation. That is not the nature of love: it lives, it breathes, it is effort and work, undivided attention. I want then to take you with me as we circle, fail, flail and outline the contours of Loy’s art, life and the questions each inspire. As Loy herself eluded any fixed meaning, this work will and can only orbit the absences, mysteries and secrets she left behind.

Mina Loy, “Stars,” 1932, mixed media on board, 31″ × 34″. Collection of Roger Conover/Photo: Luc Demers

Mina Loy was born in 1882, in London. Her father supported her artistic drive from an early age and she was able to pursue a creative education across the European continent. She had sex, married and fell pregnant, but continued her art practice in Florence, New York, Mexico City and Paris. During the time she spent in each location, she became both member and outlier of artistic movements like Modernism, Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. I see Loy as both insider and outsider, both belonging and apart, as she was never subsumed by any group or dominant strain of thought but entered into each of these encounters open to exchange and experimentation.

While this indeterminacy was partially due to Loy’s status as a woman (she was privileged for the time but she still needed to work to survive and encountered structural barriers, especially during her years in Futurist circles), Loy was also resolutely herself in an age where cultural repression, war and technological advancements both expanded and contracted the language and material means available to make and remake the self. What would you create against the suffocation of Victorian society or in challenge to fascism’s ambient fear? What is possible when work is trickling to a stop and displacement, hunger and fear are biting at your heels? The Arts Club and Gross attempt to answer these questions by presenting Loy’s life through periods defined by years and cities, discussing Loy’s work in each: Florence (1907–1916), New York (1916–1921), Paris (1923–1936), and Aspen (1953–1966). Though the exhibition also offers sections on Loy’s impact on Modernism, and her friendship with Joseph Cornell and other artists, these are positioned within the arrow of her life.

Such organization is needed for the exhibition, abundant with work and archival material, to be legible to visitors. The timeline also articulates our central question: how do you tell the story of a life? Does it start with Loy’s birth, end with her death? Where does her influence permeate still? In Loy’s prescient “Feminist Manifesto,” written in 1914 but not published until the 1980s, she voices her frustrations with the period’s feminist movement and declares a need for women to transgress social roles that predetermine their futures: roles that tie women indefinitely and inextricably to conditions of their anatomy, to sex, to unequal protections under the law, and insecure economic futures. I mention Loy’s manifesto as its claims offer a way to think about the constellations of material that make up her personhood: let’s turn to the work, the realm, the page, the canvas where she transgresses and builds futures for herself and those who came after her.

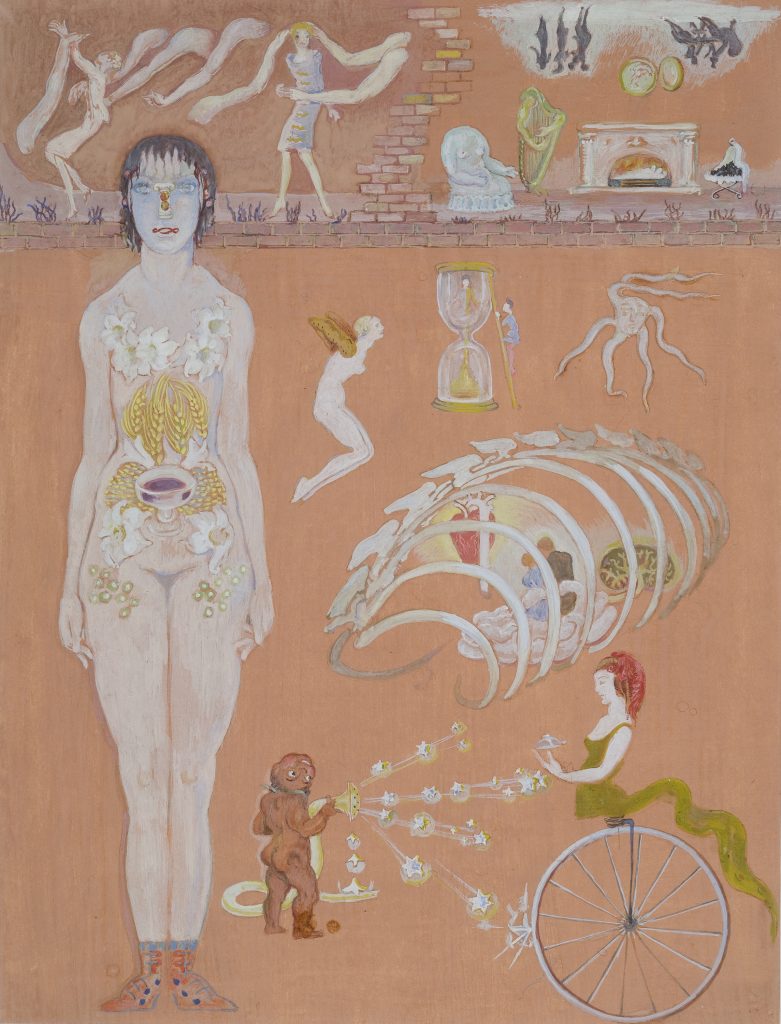

Mina Loy, “Untitled (Surreal Scene),” ca. 1935, gouache with collage on panel, 20 3/4″ × 163/4″. Private collection/Photo: Jay York

From later mixed-media works to sketches in graphite and luscious watercolor and text printed upon the gallery walls, “Strangeness” showcases the breadth and depth of Loy’s practice. “Drift Chaos III (Venus)” and “Drift of Chaos VI (Butterfly Woman),” both dated 1933, were created during a time that Loy’s life was in dire straits. She and her daughter Fabienne were living in a state of precarity: little money, little prospects, and little chance of a savior, save for themselves. Both oil paintings, one on canvas, the other on board, are night scenes. Diaphanous figures, fluttering ghosts, wander upon speckled stony outcroppings, as dark water pools at the edges of wings and veils. Outlines of classical figures, Venus’ curved marble shoulders, can be gleaned in glimpses and hushed looks. The figures are mythical and otherworldly, but they are still alone in twilight worlds where nothing is familiar, everything is permitted, and choice feels impossible. Loy completed “Prospector 2” (1954) during her later years in Aspen, Colorado. At this time, her health was failing and she lived with her daughter’s family out of necessity. The face of the prospector figure looms down upon Loy’s massive mixed-media piece, paper mounted to panel, with their mouth frozen in an avaricious leer. Flattened metal scraps rain down from under the prospector, their paper hands and sickly string hair forever reaching in a meaty grasp. The panel itself is reminiscent of a gravestone, it arches upward and juts down with force; it’s a story of a life, however small, however cruel, however debased such a life may be.

Throughout the exhibition, several of Loy’s poems are printed on the wall like way stations or signposts. Loy’s texts ask visitors to slow down, to ponder, to reach within themselves and grasp the words that whirl within like a storm; to let language sing, to let beauty dance, with ferocity. In the second stanza of “Brancusi’s Golden Bird,” Loy writes:

As if

some patient peasant God

had rubbed and rubbed

the Alpha and Omega

of Form

into a lump of metal

It’s difficult not to impose Loy’s own practice upon her ode to another artist. Though, perhaps it is this very fluidity that compels readers, makers, artists of all sorts, for haven’t you too grasped at something like eternity in your words, your colors, your lines, this Orphic choreography both within and out of your control?

***

“Then there are those who feel their own strangeness and are terrified by it.” —Katherine Dunn, “Geek Love”

What I’ve written is incomplete, imperfect, an exercise in the futile. The question of Loy, the questions of a life, are unanswerable. Perhaps. But maybe too, the edges and contours of this piece have summoned their own forms of strangeness and uncertainty. Maybe this indeed is the legacy of Loy’s voracious making: that these writings, paintings and mixed media works, are saturated by the unseen forces that drive us, make us, shape us, and leave their indelible mark. These unconscious forces, behaviors shaped both inside and out, are the strange markings of humanness. We possess no control in this world, but like Loy we can use that powerlessness to make, to create something that moves, shakes and shocks. We, like Loy, can find something like freedom as we make and remake the world. That is nothing to fear, it is a truth to be welcomed. Mystery always abounds.

Just, please, don’t call it inscrutable.

“Mina Loy: Strangeness Is Inevitable” is on view at the Arts Club of Chicago, 201 East Ontario, through June 8.