Court sketch artistry is a link to the past. It harkens back to the days when reporters would race from the courtroom to call their news desks from pay phones, often while chomping a cigar and barking things like, “Honey, get me rewrite” to whomever answered the line.

While reporters now file stories from their laptops in rooms without any trace of smoke, there are still court sketch artists in Chicago — although their days may be numbered as more and more courts allow cameras in.

Currently, there are two main sketch artists who freelance for the television news stations and newspapers in town: Lou Chukman and Cheryl “Cookie” Cook. That’s down from the days when every station and newspaper in town had their own courtroom sketch artist on staff. Now a new face, Cliff Questel, has gotten on board what may be a sinking ship.

Questel, 62, is a graphic artist by day, but recently has been seen at the George N. Leighton Criminal Courthouse — referred to by its location, “26th and Cal,” by most in the news business — as well as other courthouses in the Chicago area.

Questel initially took a stab at court sketch artistry in 2019 when his late friend, Tom Gianni, asked Questel to fill in for him. But after a couple of substitute gigs, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and closed the courtrooms. During this brief, initial flirtation, Questel met Chukman, but felt the 50-year courtroom veteran viewed him with trepidation, fearing he might steal his job. The vibe was different when they met again a few years later; soon after, Questel began to receive advice from him.

“I think he remembered that I had an interest and now he’s wanting to slow down a bit. It’s stressful, so he wants to have somebody who can sub for him,” Questel says.

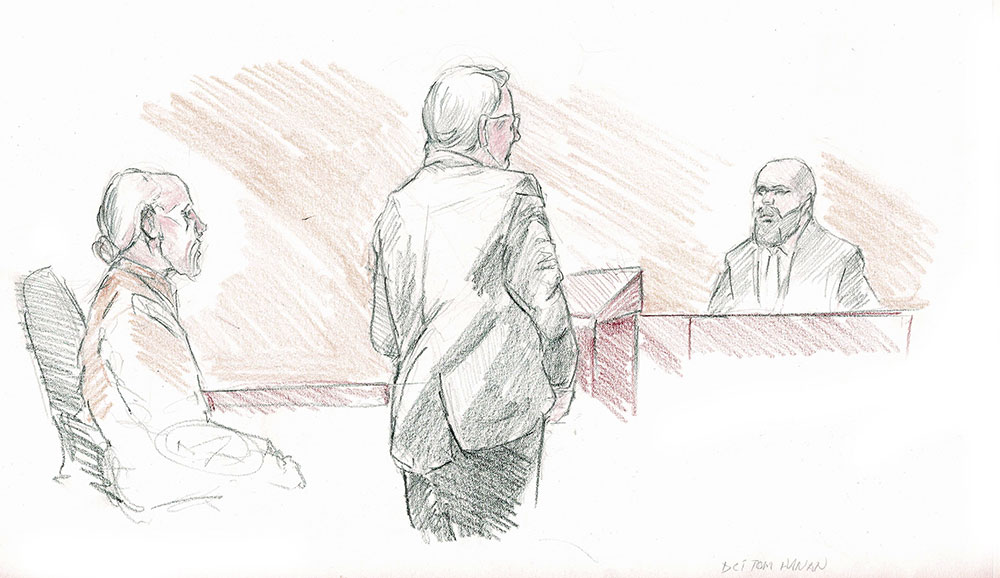

Soon after, he would accompany Chukman at bond court at 26th and California to practice, as well as at Everett M. Dirksen U.S. Courthouse for portions of the corruption trial of former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan.

“I’m pushing 70 and the Madigan trial literally put me in the hospital,” Chukman says. “It’s good to know he’s (Questel) there; he’s good and he doesn’t want to take enough of the business that’s going to cost us any business.”

Cheryl Cook, the only other court artist still working in town, says that she isn’t worried about losing jobs to Questel: She will be leaving the business soon.

“I’m past caring, I’m going to be quitting in November,” Cook says. “It doesn’t pay. It’s hard work and the stations call you at the last minute. We don’t matter to them, they don’t value it.”

Cook, 69, has been working as a sketch artist since 1982, when the field was dominated by women like Marcia Danits, Carol Renaud, and Andy Austin. Back then, cameras weren’t allowed in any courtrooms. Today, the Dirksen Federal Court is the lone exception and, while the past year was busy for Chukman and Cook with trials of Madigan, former Alderman Ed Burke, and the sons of former Sinaloa cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the truth is that the news stations are using sketch artists less and less.

“We don’t use sketch artists a lot,” says Eric Siegel, assignment editor for ABC 7 Chicago, who adds that the station would rather have a cameraman if allowed.

“We’re a TV medium so of course we’d prefer cameras,” Siegel says.

Even so, WGN-TV assignment editor Andrew Zuick says he would welcome Questel.

“It’s always good to have someone as a backup,” he says, adding the caveat that “photos and video are the way to go if we can.”

Luckily for the court sketch artists, there’s still Dirksen. And while several of the courthouses in the area allow them, cameras are usually positioned at a fixed spot in the courtroom and do not capture things that a court artist can, Cook says.

“I’ve got eyes and ears and can look around the room and find a story that a camera locked onto one chair isn’t going to find,” she says. “While a camera is pointed on one thing, sometimes in the back of the room the family of the deceased is crying their eyes out or something else is going on.”

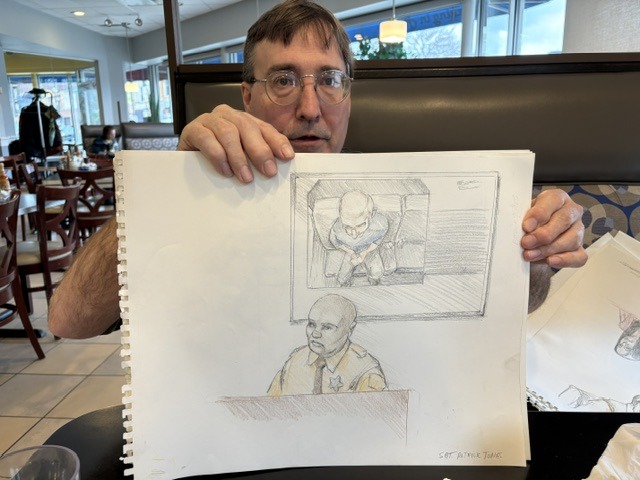

Questel agreed, and says that along with being able to tell a story with drawings, a sketch artist needs to be fast and must capture people who are not posing, something he’s still working on.

“Lou and I went to Bond Court at 26th and Cal recently and he had the whole room sketched in 15 minutes. I had two people and even the people he did were better than mine, but I know it’s just practice,” he says.

Another challenge, especially when sketching someone who is well known like Mike Madigan, is being able to capture an accurate likeness.

“If it’s a judge or defendant that the public hasn’t seen, you still want to get it right,” Questel says. “But if it’s someone like Mike Madigan who everyone knows, you better get an accurate likeness.”

Cook agrees, saying that she usually advises people thinking of being court sketch artists to practice at bus stations, airports, and coffee shops.

“Anywhere where there are lots of people,” she says. “Draw figures moving, draw people standing around, just draw because the more you do it the better you’re going to get.”

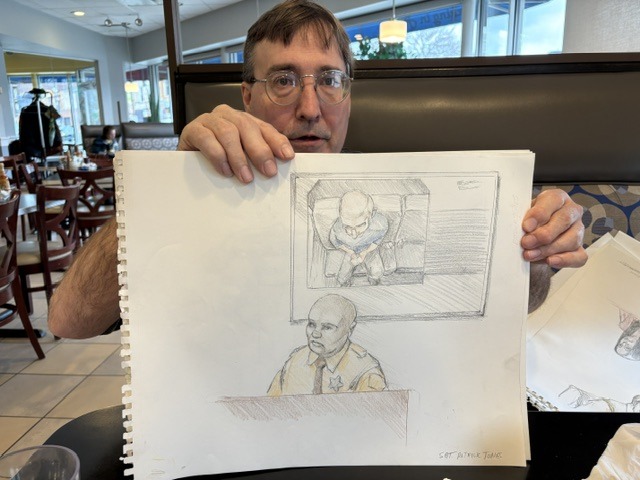

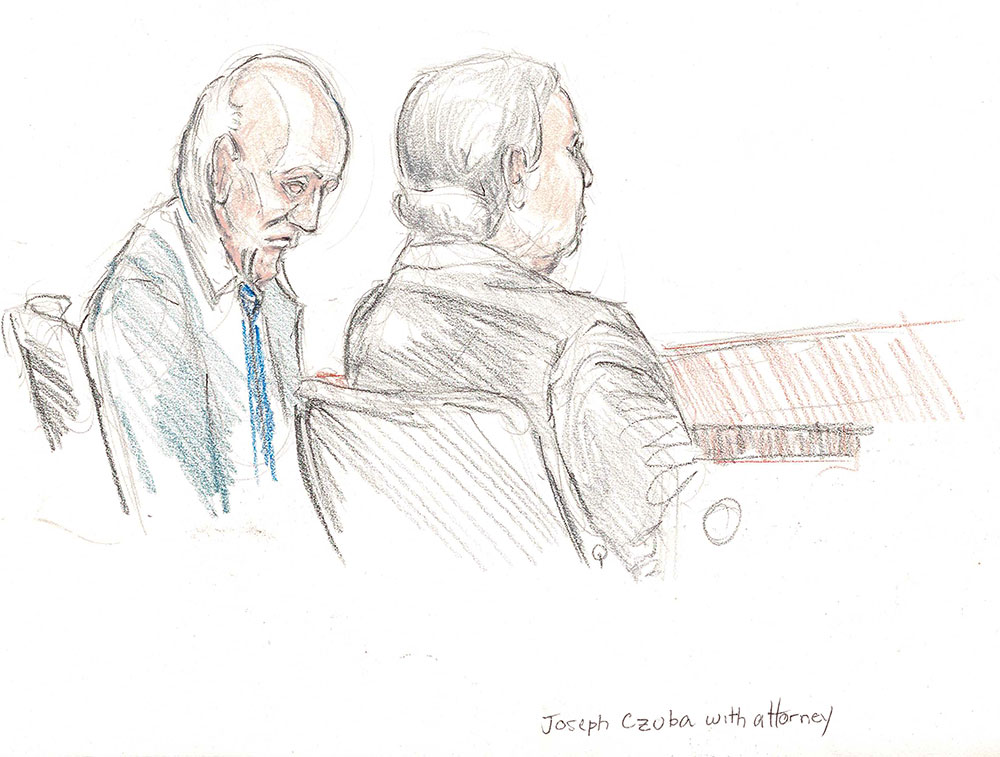

Questel has been practicing 15-20 hours a week and in February planned to get more practice by shadowing in Will County at the trial of Joseph Czuba, the man who was convicted after five days of testimony of killing a 6-year-old Palestinian-American boy and stabbing his mother in a hate-motivated attack. However, after the first day, Chukman asked him if he could take over because he was taking his first vacation in 10 years.

“He asked me if I wanted to dive into the deep end and I did,” Questel recalls, saying that he was able to sell a few of his drawings to ABC 7.

Unlike other artists, court sketch artists operate in an environment, usually criminal courts, where they often are hearing heartbreaking or gruesome testimony that can cause them stress — which is another potential obstacle.

“It’s always heartbreaking to hear about some of these cases. It will wear on you,” Cook says, adding that in her experience she’s been able to focus on the task at hand. “Without realizing it, you’re compartmentalizing it. You’ll deal with it later because you have something else that you have to get done now.”

Questel says that during the Czuba trial what he was witnessing did impact his work, especially when the lead defense attorney tried to sell the jury on the possibility that the mother, a victim in the case, could have possibly staged it — a theory that the jury rejected.

“When the defense lawyer was making his closing argument, I knew he was just doing his job, but what he was saying was appalling,” Questel says. “I was drawing him and realized that I was drawing him ugly because of it. I had to start over and block out what he was saying.”

Although Questel isn’t sure if he wants to be more than a pinch hitter for when Chukman or Cook cannot be in court, he concedes that he might like to take the baton and keep court sketch art going in Chicago, especially since his graphic arts clients are nearing retirement.

“I’m not sure if it’s a baton that I completely want to catch but if it were to happen that way, I’d be happy with it.”

For now, Questel says he will continue to practice and is ready to step in whenever Chukman or Cook need a break. While he may get more work in the future, depending on court calendars, one thing he hadn’t considered is that he may one day sketch his daughter Rose, who is set to graduate from Chicago-Kent School of Law.

“I should be able to get a likeness,” he says, laughing.