Rising country music star Charley Crockett played a set of his brand of retro-country inspired music at Louisville’s Iroquois Amphitheater this Tuesday, July 30. With him, he brought Kentucky-native country blues artist Nat Myers.

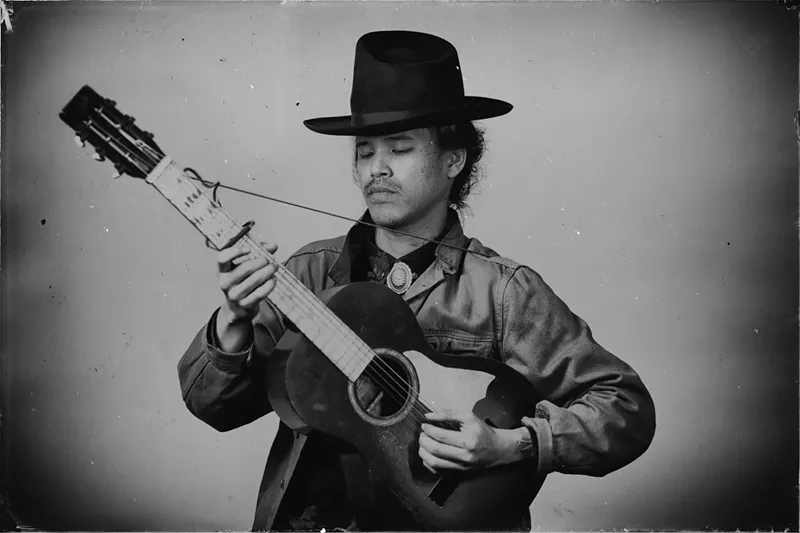

Born in Kansas but raised in Northern Kentucky, Korean-American blues artist Nat Myers plays a back-to-basics blues approach, free from electric guitars, that brings with it a feeling of old pre-war race records, with inspiration from artists like Charley Patton and Louisville’s own country blues pioneer Sylvester Weaver. We were able to talk with Nat to discuss his music and Kentucky’s relationship with the blues.

LEO: I wanted to start these questions at the beginning, so what has your musical journey been like?

Nat Myers: My musical journey started out like most folks, playing to myself in my parent’s basement and in my bedroom. I started busking on the block for a while. I was selling weed for a while in New York for a bit, I had some close calls, and I just realized [that] wasn’t really the thing for me. I started going out on the block because I had all this music I was working on. I remember up in New York and people kept suggesting this place called the Jalopy and they kind of gave me some of my first gigs. My good friend Jay Skaggs, he’s also from Northern Kentucky, he gave me, I think, my actual first gig. Besides that man, I’ve been playing for about eight years now, but things didn’t start really kicking for me until about two and a half years ago, kind of in the middle of the pandemic people started getting wind of my music. I had some early supporters like G Love and Special Sauce, I remember they reached out to me when I really didn’t have nothing going on. Some good friends of mine like Nicholas Edward Williams, who runs the American Songcatcher Podcast, I remember he did a shoutout for me. I owe a lot, honestly, to this fella named Matt Eich, he makes these guitars called Mule Guitars up in Saginaw, Michigan and he posted my stuff and that really got the train started. But in terms of where I am now, being able to open for amazing acts like Charley Crockett, I met my agents and you know, like a barbecue, just real kind of happenstance.

Your first full length album came out last year, this year your opening for Charley Crockett who has blown up recently and continues to get bigger. How do you think the response has been for your acoustic, back-to-basics kind of blues, where there isn’t a lot of that being played now?

It kind of meets the proportions of race records back in the 1930s and ‘40s, and that’s sort of my bread and butter, the sort of pre-war records. The pre-war music honestly wasn’t even being listened to much back in the day, there were a few upstarts that kind of crossed over, but for the most part the music was kind of like how it is nowadays, it kind of gets overlooked. There’s plenty of blues labels, but there aren’t a lot of labels that have been kind of cut on country blues music, the acoustic blues music that I’m doing. [My label] Easy Eye obviously has been very receptive to stuff that has that retro or like you were saying that kind of back-to-basics mentality behind it, but for the most part all the larger labels stick to their bread and butter which is the electric blues. But it’s cool man, I’m kind of part of this burgeoning scene when it comes to this country blues music / country folk music. I think it’s really going on, but I think it kind of comes down to whether the actual powers-that-be want to pay attention to it. For the most part, I think the thing about country blues players aren’t held by the trends, they ain’t really sticking cameras in their faces. But for the most part I think it comes particularly to artists like Charley Crockett, anybody kind of in this country revival that is happening from pop country to western country to what Tyler Childers would say, that being that Americana is just a costume for country music. You know, when all the water rises all the boats float, and I think I’ve found a lot of love from the country scene. I wouldn’t say I wasn’t getting any from the blues scene but it wasn’t until this past year I was playing my first blues festival and opening for blues acts.

That’s interesting you say the country music scene has been more receptive than the blues scene.

Yeah, [I think that’s because] when it boils down to it, the thing about a lot of these cats and the music their playing, their playing the five-bars or the twelve-bars but they have a little more draw, put a ten gallon hat on, and put some honky-tonk guitar behind it. For me, I think some of the best blues players are folks like Charley or Neil Emerson.

In terms of the country blues scene, I’ll shout it from the rooftops, I think Jontavious Willis is one of the best doing it right now. I think people are starting to get wind, and it’s going to continue to get proven that the excellence that comes out of the country blues scene will get acknowledged, or continue to get acknowledged.

You mentioned how the country music revival, moving away from pop country, is getting popular with folks like Tyler Childers, Charley Crockett, Sturgill Simpson, and Zach Bryan. How does it make you feel like a lot of that is coming from Kentucky with people like Tyler and Sturgill?

It makes me happy. Kentucky doesn’t really get talked about for country blues music, you know people think I’m from Mississippi or something when I play. I would say that’s a misnomer that shows the power and mainstay of what delta blues music or even piedmont has in the larger narrative of blues music. Kentucky has kind of got continuously annexed from that conversation. I think what’s interesting about Kentucky is it’s kind of its own thing and it always has been. Bluegrass and country, those exportations have always dominated the scene, but I think with country blues there is a deep legacy that occurs in Kentucky, primarily in Louisville. One of the first country blues guitar solos was done by a fella named Sylvester Weaver who grew up in Smoketown. I think there needs to be a better acknowledgement of country blues coming out of Kentucky. Again, it boils down to what exactly are the compartmentalizations you’re putting on the music, because a lot of the country musicians in the state are some of the best doing the blues right now.

I was just about to mention Sylvester Weaver when you mentioned Louisville.

If I can just harp on Sylvester Weaver for a second. I’ve been able to get close with S.G. Goodman or Kelsey Waldon, two other really great Kentucky artists, and they come from Western Kentucky and have a very different ilk in terms of perception of what Kentucky means. That part of the state they come from is right on the Mississippi river, the conduit of that river and the Ohio River continues to be one of the biggest arteries for country music. Talking to Kelsey Waldon or S.G. Goodman they really put into perspective that, regionally speaking we are this crossroads.

What are your major influences?

Oh man, those old chicken pickers back in the day. Some of those musicians [I listen to] now or are always on repeat. Sylvester Weaver is one. Charley Patton is one, they call him the “Father of the Blues.” Somebody I’ve really gotten into recently is Gene Campbell, he recorded a lot back in the 30s but he got kind of washed out as history went on.

How did you discover that sort of music?

I remember learning about guys like that after my dad introduced me to Bob Dylan who is greatly inspired by those guys like Charley Patton.

Yeah, in terms of my musical legacy, my dad listened to a wide plethora of music. I remember being a little kid and he’d be playing old country blues compilations and then you watch old home videos you’d have arthur crudup or elvis playing in the background. He had such a wide variety of musical interests and I think that enabled me as I got older and became my own what I wanted to do with music. I never really wanted to play guitar except to play blues music, I’m not interested in shifting or adjusting. A lot of people may play this music for their fans or because whatever arrows of fortune point them to, but I don’t give a goddamn about any of that, truth be told. It’s just really awesome that some folks are giving a shit about it. What it boils down to is I’m going to be playing this music in my basement now, in the past, and in the future. It’s amazing to have an audience and I hope I can keep appealing to folks generally speaking. Those deep cuts though, that’s all I really care about man. And I love me some Bob Dylan too, man.

We kind of already discussed this, but overall, how do you think being from Kentucky impacts your music?

Everything, man. I was born in Kansas but I don’t know jackshit about Kansas. Everything I’ve known growing up has been Northern Kentucky and Louisville. I think it impacts everything I do, not just my music. Just my thinking, whether it be politics or just my way of living. I think my music definitely wouldn’t be the same if I wasn’t from Kentucky. It comes down to what we were talking about with country music, and what is the nature of authenticity. I think if we look at authenticity as a concept much more so than a true or false thing, then Kentucky really has this reputation that precedes itself, and I’m so lucky to be from a state like that.