As a curator, writer, and artist, my work is grounded in storytelling. Contextualizing the work of artists past and present for broad audiences is an incredible responsibility; arts administrators play a significant role in determining whose stories are preserved in history and how they are remembered. But what about the stories that aren’t told? How can narratives historically excluded from the canon be elevated and recognized for their enduring influence?

The resolve of the Black Arts Movement to address these questions led to the cultivation of spaces for artists to express themselves freely and for folks to see themselves reflected in art. Major cities like Chicago, New York, and Oakland immediately come to mind when considering the connection between art and self-determination. However, the continuum of Black artists in Buffalo, New York, has fostered community spaces and practices for decades that center accessibility and the inextricable link between art and life.

In 1968, three Buffalo artists — James Pappas, Allie Anderson, and Clarence Scott — established a center where fine art could be accessible to inner-city residents. Through exhibitions, performances, and classes, the Langston Hughes Center for the Visual and Performing Arts became a hub for creativity and connection. The group, later joined by artists Wilhelmina Godfrey and Hal Franklin, immersed the city in the energy of the Black Arts Movement, exhibiting widely recognized artists like Richard Hunt, Abdias do Nascimento, and the Chicago-based group AfriCOBRA. However, the 1968 show of their own work, Six from the City, put them at the center of history as the first exhibition of all-Black artists in Buffalo.

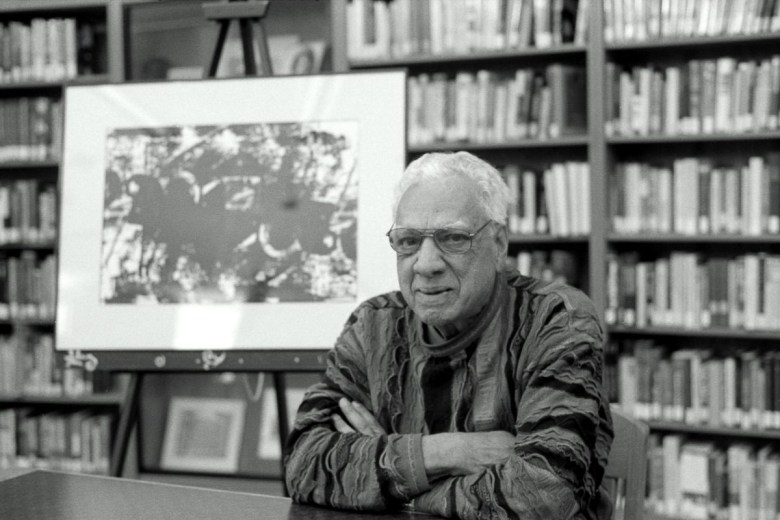

Curating the 2021 exhibition Founders at the Burchfield Penney Art Center was my first deep dive into the Langston Hughes Center’s early history and the expansive local network of Black artists and cultural spaces. It was also the first written record of the center’s early years, which previously had lived only in the memories of those who experienced it firsthand. Working closely with James Pappas, the center’s visionary and internationally recognized artist and educator, revealed a rich legacy that would be an incredible loss if not preserved.

At the heart of Pappas’s prolific body of work is a lifelong love of jazz, seen in the rhythmic abstractions of his paintings, prints, and high-contrast photographs of some of the genre’s greats. Works like the harmonious “Innerspace Continuum #7” reflect the timeless interrelations between music and visual art; the soft pastels and organic forms resemble the horns and pulsating vibrations of a jazzy rhythm. His incredible professional accomplishments and artistic practice resonate with a spirit of freedom and Black culture at its most dynamic.

Even with a clear musical influence, Pappas invites viewers to bring their own interpretations to his work. To me, the discrete colorful forms in his paintings cohere into a fragmented image of the self. Like each composition, one’s identity has no beginning or ending; it is, rather, a continuous evolution and journey of discovery. I think about the spaces we move through to find ourselves and the ways Black identities have had to grow, change, expand, or shrink within them. Creative spaces amplify art as an outlet to construct and reconstruct our many layers freely and share them with others. For Pappas, the center was rich with the potential to show the importance of art in everyday life, to inspire young artists to pursue a professional art career, and to encourage folks to discover new facets of their creativity.

“Through art and the creative process, many people began to learn and understand themselves and explore things they never did,” he reflected in conversation. “That was a kind of excitement for me.”

Pappas’s colorful assemblage of motifs is a reminder that fluidity is essential to the many parts that make us whole and to uncovering new aspects of the self through art. Young artists at the center were offered an opportunity to experiment not always afforded to people of color; they were encouraged to try different media and means of expression. His ability to move seamlessly between painting, screen-printing, and photography embodies this ethos in practice.

Learning this history has greatly influenced my own journey of self-discovery, particularly my identity as a storyteller enacted via my curatorial practice and photography. By resisting assumptions that the roles of artist and curator are mutually exclusive, I ask myself how my curatorial work can inspire my artistic voice. This question encourages me to not only explore these artistic legacies through exhibitions but also photograph the process of connecting with the people and places central to it.

The history Pappas and his contemporaries created is continuously built upon as new cultural spaces and organizations emerge. Its community-minded ethos is reflected in my own work and that of so many local artists I’ve come to know.

Painter and former teaching artist Betty Pitts Foster is one witness to the evolution of Buffalo’s Black arts scene. To her, it exudes a feeling of “no limits.” Using a warm, soft palette, she creates meditative observations of the world around her, finding beauty in the subtleties of everyday experiences. She employs a loose, gestural style to depict abstract landscapes filled with color and light, as well as populated scenes of day-to-day life. Citing the inextricable link between her artwork and religious beliefs, her work celebrates the small joys of living.

“You come to the realization of who you are,” she noted to me. “Once you come to that realization, the doors open.”

Her painting “Crossing Elmwood” feels emblematic of what I see in the Langston Hughes Center legacy and in the city’s welcoming creative landscape. I see elders embracing the next generation, guiding them along the paths they once walked. Crossing paths with others along the way, these interactions leave their impressions on our journeys of self-realization. As I witness the evolution of Buffalo’s arts community and shape my own role within it, the potential of how it’s remembered in history feels full of possibility.