On the twenty-first of April 2021, snow began to fall on St. Louis, Missouri. It wouldn’t have been unusual on a late spring day, except that it hadn’t snowed on that date since 1904.

The fact didn’t go unnoticed by Janna Añonuevo Langholz, a Filipina-American who was born and raised there. She had been researching on an Igorot woman named Maura who had been part of the Philippine Exhibition of the 1904 World’s Fair, the spectacular event meant to showcase the achievements of the newly minted American global empire.

“When I referred to newspaper articles on that day in 1904, I learned that Maura died the next day from pneumonia,” said Añonuevo. “I wanted to pay respects to her and bring flowers to her grave, but I wasn’t able to find it.”

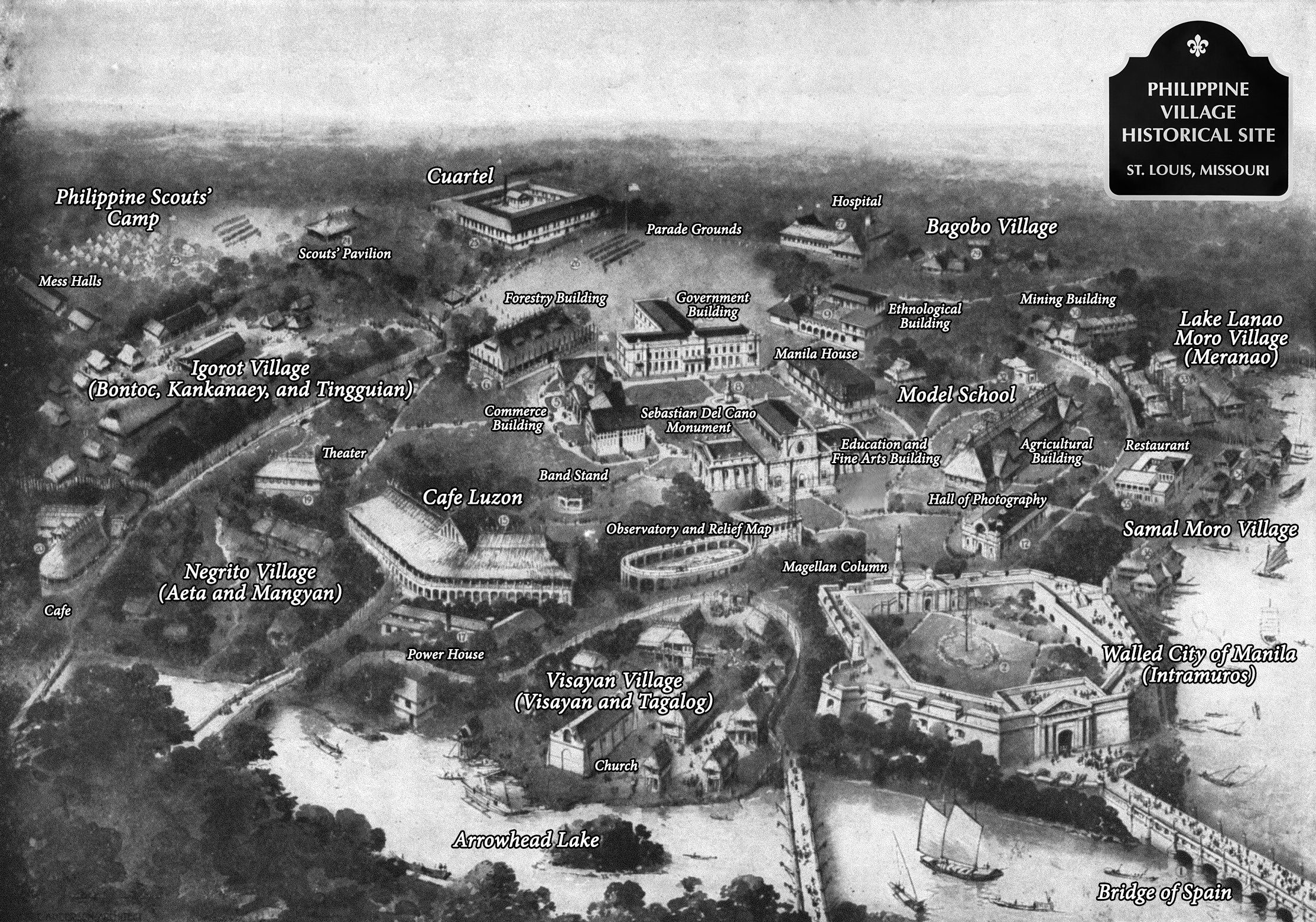

So began an improbable site-specific project to locate and commemorate the Filipinos who had been displayed in what today can only be seen as a blatantly racist “human diorama” of America’s conquered peoples.

This year marks 120 years since the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, organized to celebrate centennial of the Louisiana Purchase, a “fantastic real estate deal,” says the city’s web site, which significantly expanded the United States. Later, the nation’s policy of “manifest destiny” extended that expansion across Native American lands and further towards the Caribbean and the Philippines.

The fair, if it is remembered at all, continues to serve as a milestone of American exceptionalism. But still very few are aware of the plight of over a thousand Filipinos who were shipped to the site from various locations in the archipelago.

The city of St. Louis heralds the fair as one of its historical landmarks and constructed the World’s Fair Pavilion on the site of the fair’s original Missouri Building as “a lasting memorial to the Fair.”

Nonetheless, memorializing the conquered nations who were displayed at the fair – the Philippine Exhibition proved to be one of the most successful – continues to be an uncomfortable topic in America.

But thanks to Añonuevo’s efforts, the city of Clayton, Missouri, has paid attention, and last summer approved a proposal to erect a permanent commemorative marker honoring the historical site of the “Philippine Village.”

It’s one crucial step towards reckoning with the fact that race has always been at the heart of the historical relationship between Filipinos and the United States. Artists like her have worked in their own way to address this issue, which renders the Filipino invisible in the greater American narrative. A few scholars have tackled the subject, including Paul A. Kramer’s The Blood of Government, a study on race and empire in the Philippines, and Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire.

But in the US, discussions on race often become a black vs white issue, leaving Asian Americans largely marginalized. When Asian Americans are the topic, it mostly centers on East Asians, leaving other groups like Filipinos invisible.

“When I explain the fair to Americans in general, I talk about all the people who fell in love at the fair,” says Añonuevo. “I talk about the people who were born and the people who died. I talk about moments when residents of the Philippine Village exercised agency within confinement and made the most of the situation. If we continue to talk about the Philippine Village as a zoo, we continue to dehumanize our own people and ourselves.”

Humanizing the Filipino is what Marlon Fuentes does in Bontoc Eulogy, the seminal film on the St. Louis World’s Fair that he wrote, produced, and directed in 1995.

Bontoc Eulogy combines history and fiction about a Fil-Am man who ruminates on the disappearance of his “grandfather” after he was exhibited at the World’s Fair. The first to examine the historical and generational repercussions of 1904, the film examines the importance of memory in identity-formation, an issue that permeates all immigrant communities of color in America, and that is especially resonant to Fil-Am artists and intellectuals.

Fuentes believes that the Filipino remains invisible because visibility comes with a community’s economic success. “It’s just about the higher visibility of Japanese, Chinese/Taiwanese, and South Korean cultures that have a tremendous amount of economic success compared to other ‘brown Asians’ like us. It’s all about the old ‘follow the money’ dictum.”

According to the Pew Research Center, very few Asians born in America are aware of Asian history in the US. But artists like Añonuevo and Fuentes have been changing that for the Filipino American community.

Fuentes argues that “there are two primary idioms of intervention,” including research and scholarship as well as art. “I’m more excited by the possibility of combining the two idioms,” he says. “Bontoc Eulogy is an example of the ‘hybridized’ idiom.”

Añonuevo believes addressing Filipino invisibility begins with exploring her own personal history. “When we start to reconnect with our communities, I think that’s when we become strong both individually and collectively,” she says. “Filipino invisibility in the media in the US is something that has been one of the main driving factors of my work. Within the context of the Philippine Village, a place that is now nonexistent and yet I am surrounded by, making that history visible is healing to me. As difficult as that history can be to confront, I think it also provides a space to be seen. Maybe the reason it’s invisible is because we didn’t know where to look.”

“Fil-Am identity is a dynamic and evolving idea,” says Fuentes. “Like any morphology, it has to be viewed from a historical/evolutionary lens. That’s why 1904 is such a sweet spot to begin with, since it incorporates both past, current, and future imaginings within the context of a self-reflexive position.”

Añonuevo says she grew up in the “ruins” of the St. Louis World’s Fair, which contributed to the formation of her identity as a Fil-Am. “I didn’t meet my family in the Philippines until I was 18, so that part of my identity was closed off to me for a long time. I didn’t know what it meant to be Filipino or Fil-Am. Contextualizing my identity within the World’s Fair is the only thing that makes sense to me because why else would I be here today?”

Both hope that their work today will help future generations of Filipinos and Fil-Ams. “I want them to remember the real stories, not the mythologies,” says Añonuevo. “Those people were brave, strong, and resilient, and must be honored for everything they sacrificed in coming to St. Louis.”

But Fuentes also has a warning. “St. Louis is probably one of the most successful historical displays of economic and market power the world has ever seen,” he says. “Take notice of the underlying narrative infrastructure that allowed the Fair to happen. Now take a look at our current social and political situation. How is it different? How is it the same? The more things change, the more things remain the same.” – Rappler.com

Eric Gamalinda teaches at the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race at Columbia University. A new and expanded edition of his collection of poems, Amigo Warfare, was recently released by Ateneo de Manila University Press.