Back to the future!

With recent biographies of Madonna and Lou Reed, and memoirs such as Ada Calhoun‘s “St. Marks Is Dead,” writers are avidly trading on nostalgia for the East Village scene of the 1980s, conjuring spray-paint and punk bands, boom boxes and break dancers, sex and drugs — the heady brew that made careers and ruined lives.

Brad Gooch’s trenchant “Radiant” captures the era through the prism of Keith Haring (1958-1990), whose iconographic drawings and sculpture cemented the legacy of pop art before he succumbed to AIDS at 31. Many of his pieces will be on display as part of an exhibit at the Walker Art Center, opening April 27.

Raised in a conservative middle-class family in Kutztown, Pa., Haring manifested a talent for sketching cartoon characters and balloon typography. Gooch depicts Haring’s early years with finesse, charting a trajectory from adolescent Jesus freak to blissed-out Deadhead to rebellious student at Manhattan’s School for the Visual Arts.

Encounters with street artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf led him to ditch education and embrace the subway and sidewalks as his canvases. Haring bridged the gallery milieu with commuters on the F and 1 lines. (The “Chalkman” chapter on his chalk art is worth the price of the hardcover.)

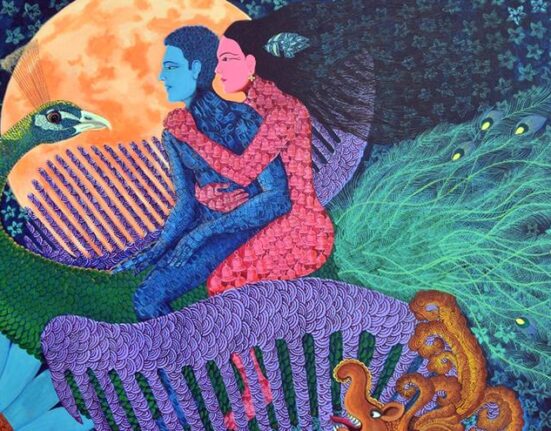

He drove himself at a punishing pace, seeking collaborators as frequently as bathhouse hookups, settling down twice, with Juan Dubose and Juan Rivera. Scale was no obstacle: Haring worked on postcards alongside wall murals, obsessed with the possibilities of lines. His hieroglyphic motifs — barking dogs, sinuous snakes, erect penises, his “radiant baby” tag — heralded the arrival of a stellar draftsman who absorbed the breakthroughs of postwar painters trained in commercial techniques: James Rosenquist, Willem de Kooning, and especially Andy Warhol. Fame and fortune beckoned.

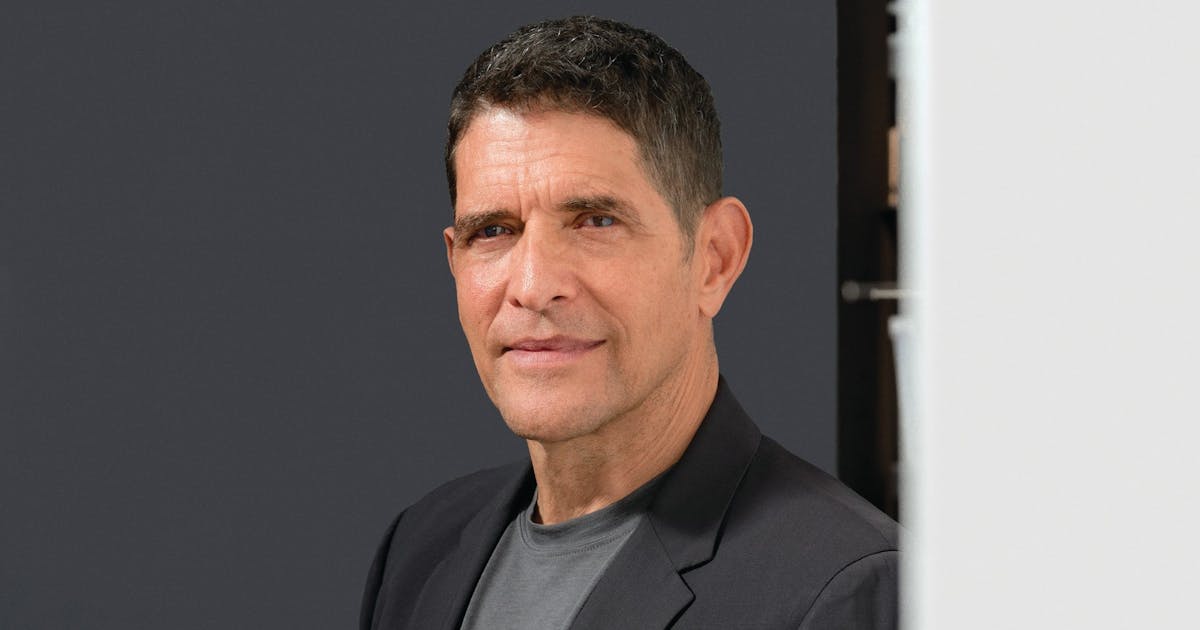

Gooch’s extensive research creates a seductive portrait of the artist as a young man, one whose image forever remains a lanky, boyish figure with nerdy glasses and an affinity for children. But Haring was equal parts radiant naïf and enfant terrible, and the biography tackles his hedonism and controlling nature.

His intelligence stood out from the frenetic energy around him: His dealer, Tony Shafrazi, noted the way Haring “was so organized and systematic, efficient and fast, washing all the tools and brushes afterwards, laying them on the floor in an orderly fashion.”

As in previous books on Frank O’Hara and Flannery O’Connor, Gooch writes bourbon-smooth prose, although he occasionally mimics the gossipy tone of Warhol’s diaries. The question of whether Haring “sold out” hovers over “Radiant” like an unanswered prayer; I wanted fewer boldfaced names and deeper analysis of the oeuvre.

Gooch regains his stride when Haring’s compositions became overtly political, critiquing the Reagan administration’s indifference to the AIDS pandemic and the atrocities of South African apartheid. Haring opened Pop Shop in Soho, merchandising his brand, guided by Warhol’s subversion of aesthetic values to a matrix of business and celebrity cachet. Staring down his own diagnosis and mortality, he kept up his routines, traveling to a Paris show a month before his death.

“Keith was a case study in blooming where you are planted,” Gooch observes. “His ability to make the most of face-to-face opportunities could turn a belief in chance and accident into a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Hamilton Cain, who reviews for a range of venues including the New York Times Book Review and Washington Post, lives in Brooklyn.

Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring

By: Brad Gooch.

Publisher: Harper, 439 pages, $40.