MOSCOW — “We live in an intolerant environment,” Eugene, a former member of the Russian capital’s drag collectives, told The Moscow Times while walking near a nightclub in the city center where he and his fellow artists used to work.

That sentiment, Eugene said, is shared by drag artists who play with gender stereotypes, norms and expression as well as many LGBTQ+ people and advocates for freedom of expression in Russia.

Amid the Kremlin’s wider push for “traditional values,” Russia last year added the so-called “international LGBT public movement” to its list of terrorists and extremists, putting at risk of fines and criminal prosecution anyone who has publicly associated with LGBTQ+ lifestyles or symbols, activists said.

In December 2023, police raided a number of Moscow nightclubs shortly after Russia’s top court banned the “international LGBT movement.”

The St. Petersburg gay club Central Station and the Moscow club Secret, which both hosted drag performances, were forced to shut down. A queer bar in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk also closed in February after a police raid over a performance where drag artists were seen dancing in soldiers’ uniforms.

The Moscow Times spoke to Eugene about the lives of drag artists and LGBTQ+ people in modern Russia.

Eugene, 21, asked not to reveal his full name due to the risk of being prosecuted under Russia’s anti-LGBTQ+ legislation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MT: How did you become interested in drag culture?

E: I’ve always been intrigued by the nightlife scene in Moscow. That’s why, around three years ago, my friend and I decided to go to a nightclub after seeing a poster on social media advertising a big show with artists and dancing. Up until that point, I wasn’t very familiar with drag culture, or at least, I knew very little about it. But from the first moments, I witnessed something incredible. I was truly inspired and captivated by what I saw on stage — the show, the costumes, the music. I felt a sense of freedom, unlike anything I’d experienced before.

Later, I began going to nightclubs more often. I was already involved in chat groups [with drag artists] where there was always a very friendly and supportive atmosphere. I also started assisting with various tasks for drag performances, such as buying fake eyelashes or glitter. Most of my work involved special effects — I often mixed edible artificial blood, which washed off white fabrics very well, so that was quite cool. Once, during a show, I created an artificial fire. Initially, I participated behind the scenes, helping with performances and decorations, but eventually, I found myself on stage as an actor and dancer. I never thought I was capable of dancing like that in front of a large audience. It was quite an experience.

MT: Was there a feeling at that time that doing this might become unsafe in some way?

E: No, I didn’t think that I was of any interest to anyone. All my concerns revolved around my friends and relatives. I had to say that I was working night shifts or staying at my friends’ places, making up excuses.

In terms of relatives, we live in an intolerant environment. Some of my relatives — I can’t say that they directly support the war [against Ukraine] — but they made statements that seemed controversial to me. It seems that when a person strongly opposes something they don’t understand, such as other cultures, they may use indecent expressions toward people from other countries. They later extend this attitude to people from the LGBTQ+ community. That’s why I stopped trying to show them the performances and costumes we created after a few unsuccessful attempts. They just shrugged their shoulders.

MT: How did the Russian drag community respond to the tightening of anti-LGBTQ+ laws?

E: Our club banned filming and taking photos inside to avoid putting anyone at risk. Everyone had concerns… Many artists have other jobs, as drag isn’t very developed in our conservative country and is mostly a hobby. Of course, they [drag artists] have other aspects of their lives that we may not even be aware of. It’s frightening to think that a data leak could jeopardize their entire lives.

After the laws were tightened, there were several waves of anxiety, so to speak. For example, sometimes men with very bright makeup and ostentatious clothes were not allowed into the club as spectators. Perhaps the club did not want to attract unnecessary attention to itself, as there had been several police raids prompted by dissatisfied visitors.

There were also situations when law enforcement authorities came and the artists were informed. One of the artists quickly shoved all their belongings into their suitcases and rushed out of the club; others didn’t have time. There were fears that we would be accused of so-called ‘LGBT propaganda.’

I’m glad that occasionally, some drag performances still incorporate political messages. Though technically it’s not permitted, these messages are often conveyed allegorically, buried within the performance. One drag artist expressed wishes for love and good health, adding a wish for a future where we could all use Instagram without needing a VPN. This phrase struck me because it wasn’t just about a specific social network that is banned by the country’s authorities — it spoke to a broader notion of freedom within society.

MT: How have the tightening restrictions affected you personally?

E: When the first recent changes happened [in 2022, when Russia expanded its ban on ‘LGBT propaganda’ to encompass content aimed at all ages] I couldn’t believe it at all. And what hit us the hardest, probably, was the adoption of the ‘transgender law’ [in 2023, Russia banned transgender people from accessing gender-affirming services]. This is very scary, because you realize that the state has been given some power over the bodies and feelings of other people. It’s also scary because my transgender friends have received military summonses [to fight in Ukraine], both trans men and trans women. You sense that sooner or later, this may affect your loved ones. I truly wish for everyone, including myself, to feel safe. Unfortunately, not everyone has the opportunity to leave or protect themselves in any way.

MT: Do you feel safe in Russia?

E: Honestly, this whole dictatorship with its restrictions is the opposite of what it should be — a state that protects you. You’d rather turn anywhere but to law enforcement agencies, even when it’s about personal safety. [After drag performances] you think in advance about what you’ll say about your look if someone asks, especially when it involves security agencies but also just a passerby. You always need to come up with excuses to secure everything somehow. Often, even without paying attention to how you dress or behave, you end up saying the same things as always. So sometimes people come up to you and ask very strange questions.

MT: What are your thoughts on the future?

E: Certainly, I want to remain optimistic, but I strive to approach life with a realistic perspective. Personally, I find it unlikely that there will be significant positive changes in the next 20-30 years. While there may be some hope now, it appears faint and unrealistic. I attend various [LGBTQ+] gatherings and meetings which are becoming even more exclusive and closed. LGBTQ+ organizations will likely continue to exist as local Telegram chats under different aliases.

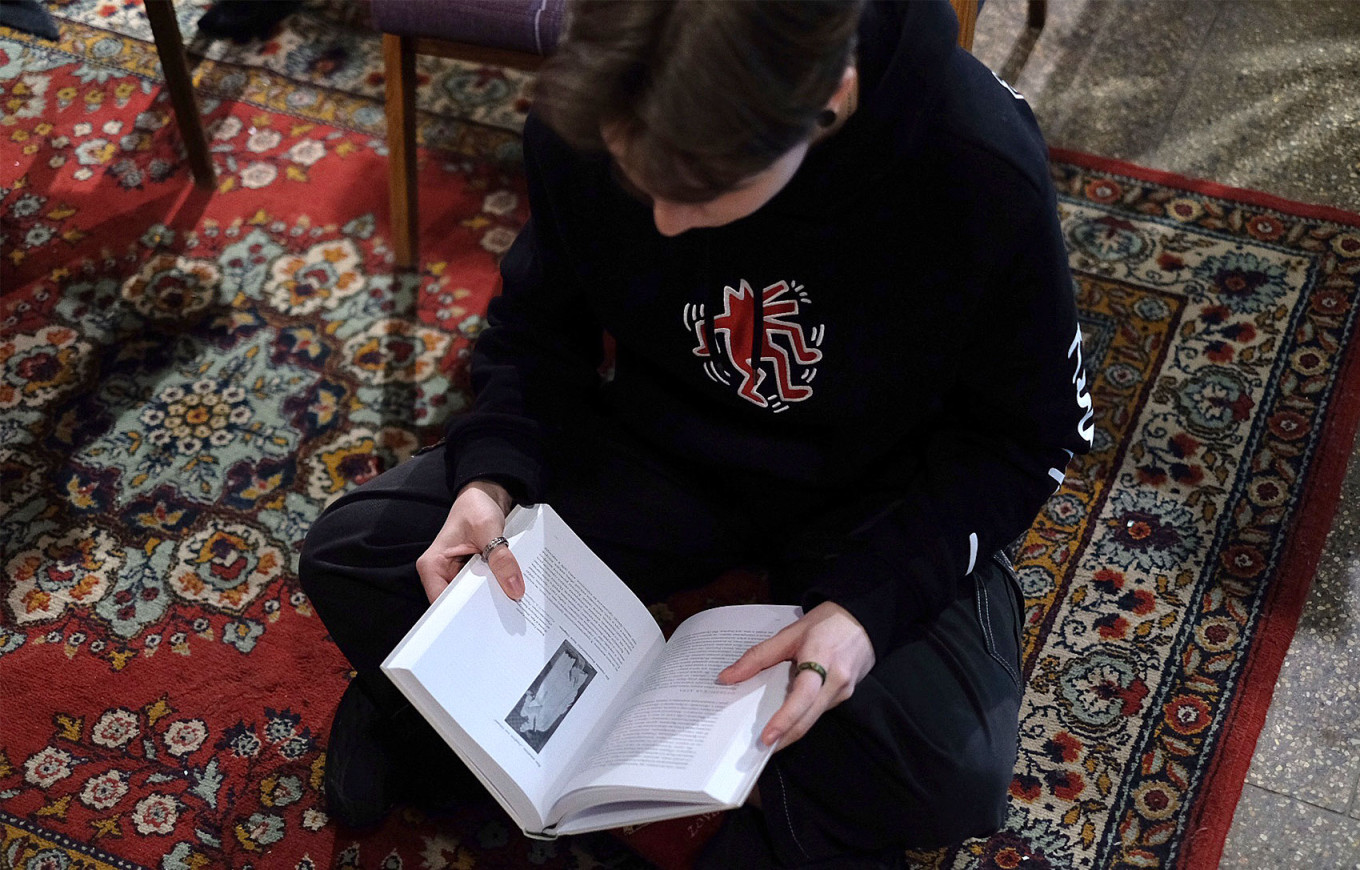

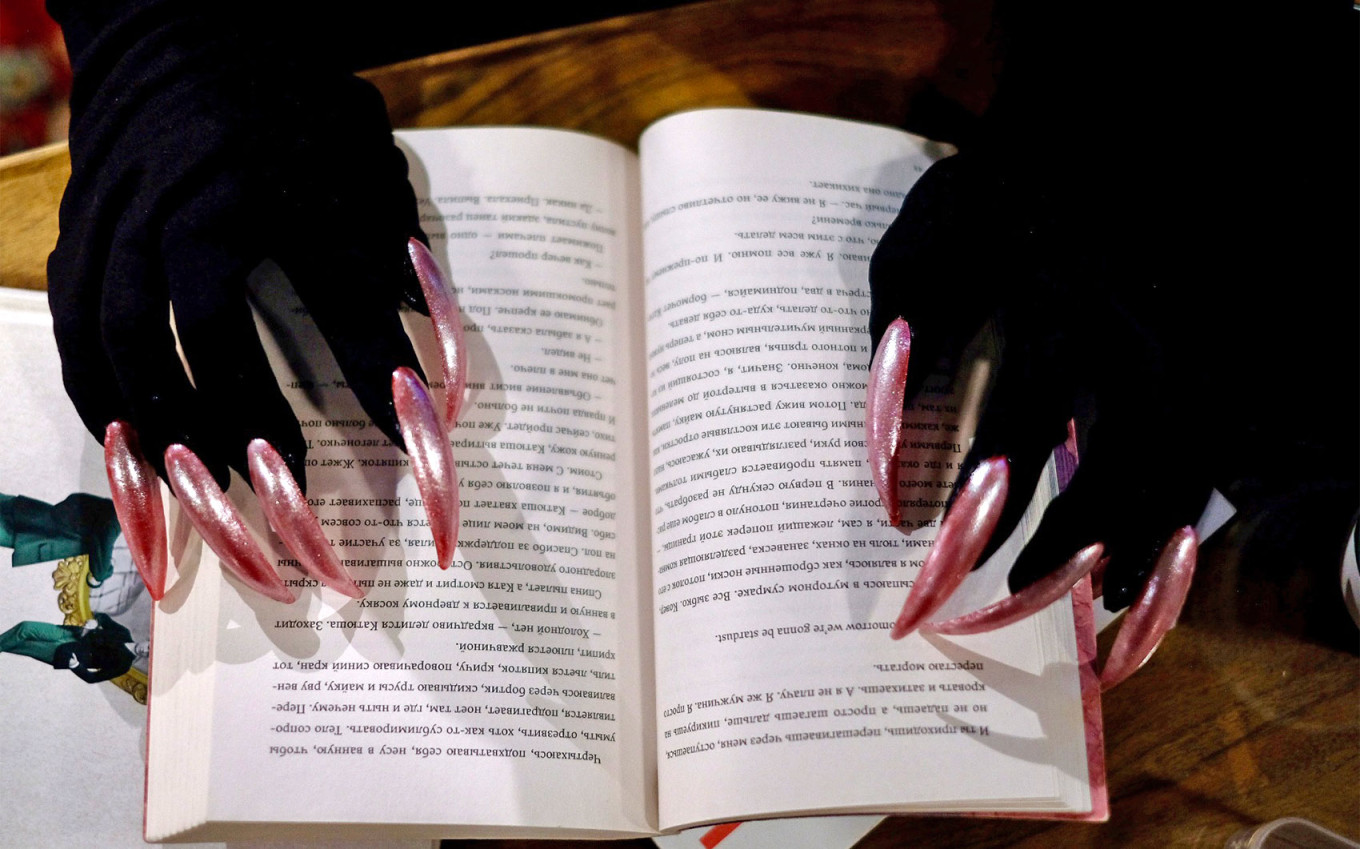

There are already clandestine gatherings taking place, including underground parties hosted at homes. I plan to attend one such event. Additionally, some drag artists arrange gatherings or private screenings of queer films in their homes or other private venues. When yet another restrictive law was adopted, my friends and I immediately rushed to buy books because we were afraid that they would disappear from sale, particularly literature on gender studies and queer literature. I have several shelves of these books at home now. One friend of mine occasionally invites me to closed literary readings focused on LGBTQ+ themes.

I think that we will just go underground.

… we have a small favor to ask. As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and you can be confident that you’re making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.